We live in an age where doubt is lionized, often pitted against a strawman of faith in which to doubt is to be thoughtful and to believe–truly believe–is to powerwash your thinker. You can get along with categories like that a lot of days, but the place where I see things collapse and scramble is at death. Death is a little like birth for the steepness of its awe and fear. We lose our footing in the presence of both birth and death. As writer and funeral director Thomas Lynch writes: “At one end of life the community declares It’s alive, it stinks, we’d better do something. At the other end we echo, It’s dead, it stinks, we’d better do something” (The Undertaking, p.157). And not only do something–birth and death compel us to believe something. The momentous has happened. That’s why people reach for names for their newborns freighted with meaning–heritage and faith and virtue. We know we have to respond to the moment somehow. We hanker for meaning. The bush is burning on the mountain and we cannot turn away. No one even needs to tell us to take off our shoes.

I see this hankering struggle for meaning happen in funerals. Funerals are part and parcel of the pastoral biz, and people approach the death of a loved one with all sorts of belief structures, from traditional Christian understandings of the afterlife to a sort of sciencey nobody-here-but-us-quarks mentality. Lots of folks fall somewhere in between. They sense a mystery yawning open before them. They intuit that more than the ceasing of a bundle of biological processes has taken place. They want to believe that there’s something beyond this life in store for their loved one, and they hope to see the person again.

So too, I’ve discovered that there are also a whole lot of people who want to believe but aren’t sure how or what. When speaking of heaven with one elderly Christian, a faithful churchgoer all his life, he responded, “I guess that’s what we believe.” It’s not that Christian heaven seems baroque or unscientific, but rather so many people have picked up somewhere that the traditional stories are somehow childish. For others, intellectual honesty means not putting too fine and fervent a point on believing. Hold it lightly and hopefully. Or maybe doubt just seems hipper.

When we approach death’s dark door, all of us start searching for something true and mysterious. I remember when my mother died a couple of years ago, a relative sought to comfort me by saying, “Someday we’ll know why.” (Hand pat. Hand pat.) His words felt like a category error to me. We’ll know why? I suppose some might wonder why, but I wasn’t. My Christian faith pointed me in a different direction. Death happens. What I was looking for was a sign of how the One who holds the keys of death and Hades was holding my mother–and all of us–just then (Revelation 1:18). I wanted the non-rhyming, lopsided poetry of liturgy and accompaniment, not certainty. I needed a sign of Christ’s life and presence.

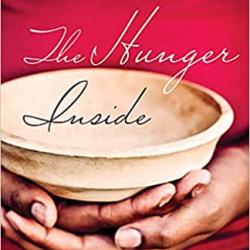

Where I have found that sign of life and presence is at the communion table–strangely enough for someone from a supposedly nonsacramental tradition. Intellectually speaking, there’s plenty to say about what happens in the bread and cup. But communion is not an intellectual construct. It’s an encounter. We take seriously the surprised words of those long ago disciples who discovered Christ “made known to them in the breaking of the bread” (Luke 24:35). I’ve been reflecting on the meaning of communion for my upcoming book, The Hunger Inside: How the Meal Jesus Gave Transforms Lives. What strikes me is how Jesus shows up again and again, pegging our lives to a presence running deeper than life and death. Confronted with the grave, the Lord’s presence at his table also summons us to a hope for something more. It’s Scripture’s long narrative, history at the end of its rope where we find Zion, the heavenly Jerusalem, God with his people. All the whys are not sewn up or the loose ends knotted. But Jesus who is real here and now stands there and then.

Which is where All Saints Day comes in, the church’s ancient celebration of those beloved believers who have arrived with Christ at their eternal home. Truly the cloud of witnesses surrounds us, table then and table now, and we’re journeying toward Christ by both. To share in Christ’s table now gives us a sign of his life to come. The prayer after communion in the Catholic liturgy for All Saints says it in a lovely way. We ask for God’s grace that “we may pass from this pilgrim table to the banquet of our heavenly homeland.”

That present/future table gives me, at least, enough to go on.