Harvard Business Review’s Herminia Ibarra wrote a fascinating overview of how people make sustainable career changes, breaking it down into three steps: separation, liminality, and reintegration. Collectively, she calls this three-step process the cycle of transition. The article is well worth reading, as is her other work on this subject.

The changes we make in our internal lives often follow similar patterns.

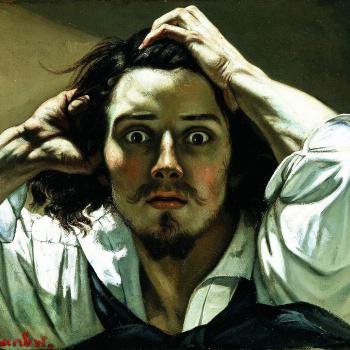

Separation

Whether we’re talking about the Hebrews in the Sinai desert, Jesus in the desert of Judah, Muhammad at Hira, or the Buddha at Bodh Gaya, almost every major story of religious awakening begins with some period of withdrawal from the person’s former life. This withdrawal marks the end of a new way of living and the beginning of a new one.

This is generally not a very exciting process to watch, which is why in movies it’s generally reduced to a training montage.

In spiritual life, this also does not often take the form of a literal separation. During Lent or Ramadan, for example, we separate ourselves from only some aspects of our lives in order to seek transformation. It also tends to be a cyclical, ongoing process towards something rather than a definitive change with a clear, measurable goal.

Liminality

When you separate from your old patterns, you free yourself up for new ones. So for example during Yom Kippur, Lent, or Ramadan, we might have our fasting and abstinence practices but we also take on a more rigorous prayer schedule. Ibarra describes this as a phase in which one might experiment, and there is always room for experimentation within your religious life—visiting other congregations, taking a short class on a religious subject you’ve never examined closely before, or just making new friends. Or you might take on a directed liminality where you orient yourself around connecting to a specific community or practice.

Reintegration

Once you’ve separated yourself from your ordinary habits and dipped your toes into new ones, you can settle into a new routine that incorporates these changes.

This is not necessarily rewarded by our novelty-driven culture! The objective by some metrics is to avoid getting into a routine at all, to stay in that liminality phase and keep separating and experimenting for the rest of your days. I don’t mean to disparage that approach, but there are disadvantages to it that need to be acknowledged and seldom are. Self-acceptance, for one thing, becomes harder without stability and routine. A sense of being rejected and alienated may follow. It is very hard to keep doing new, exciting things that you’re glad you did; there is a place for contentment and sustainable habits, for “settling,” for making a nest out of your life even as you direct yourself towards ongoing change.

It is also important not to be too hard on yourself if you settle back into your old ways. There’s a reason the religious holidays I’ve mentioned here provide an opportunity for a new cycle of transition every year, and it’s not just so that we can keep climbing higher and higher; it’s so that we can keep trying again and again, and not give up on ourselves in the meantime.