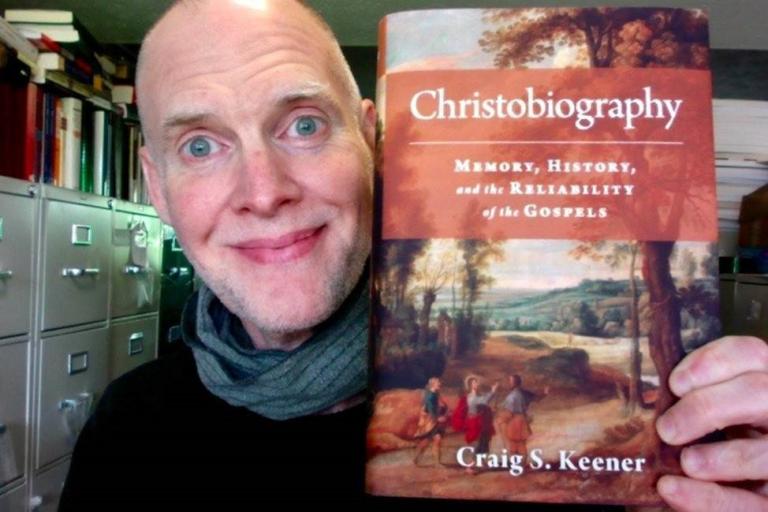

I recently had the pleasure of interviewing biblical scholar, Dr. Craig S. Keener, Professor of New Testament at Asbury Theological Seminary. He has authored many books, together which have sold more than 1 million copies worldwide. Recently, he has written an important book entitled, Christobiography: Memory, History, and the Reliability of the Gospels (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2019).

Craig, whom I consider a fellow scholar and friend, has agreed to answer several questions about his recent book, Christobiography:

B. J. Oropeza: You recently wrote Christobiography, which focuses on historical reliability of the Gospels, memory, and reading Jesus in the genre of ancient biography. This book has received positive reviews from well-known scholars such as Richard Bauckham, James D. G. Dunn, Craig A. Evans, David Aune, and others. What do you consider to be the main points you are wanting to make in this book?

Craig Keener: The genre range of biography developed over the centuries, but the apex of historiographic concern in the development of ancient biography was in the early empire–broadly in the period between Cornelius Nepos in the late Roman republic to Diogenes Laertius in the early third century, but especially in the first and second centuries. Not everyone followed this ideal perfectly, but the ideal was (and therefore our usual default expectation should be) that biographers, like historians, drew on events in their sources.

They were not supposed to invent events. They were supposed to accurately represent their subjects’ character as they saw it. That is, they had historical intention by the standards of ancient historiography, which was to teach lessons (moral, political, military, etc.) on the basis of real events, or at least events that they found in sources they considered to be respectable and historically informative.

How accurate were they? There was a range of how closely they followed their sources, but again, you were not supposed to invent events or knowingly distort the person’s character (or the teacher’s teaching, in biographies of sages). Aside from particular authors’ preferences, distance from the events made an important difference for how to evaluate reliability. When historians and biographers wrote about figures many centuries earlier, they often admitted that their material was shrouded in legend and myth. When they wrote about recent history, however, they often consulted eyewitnesses or as close to such sources as they could get.

The first-century Gospels are not written about a figure who lived centuries earlier; by definition of them being from the first century, these Gospels are within living memory of Jesus’s public ministry (c. 30 CE). In oral historiography, living memory is a period of some 80-100 years, whereas Mark’s Gospel is usually dated already within about 40 years of Jesus’s public ministry. Memories can certainly vary within this period, but major distortions in oral tradition usually do not become substantive until later.

Historians who emphasize social memory, such as Barry Schwartz, have shown that core memories (albeit not interpretive perspectives) can be surprisingly resilient in the early period. With the Gospels, then, we should expect that they largely depict early Jesus followers’ genuine memories about Jesus (of course, interpreted from their post-resurrection perspectives). This becomes even likelier when we explore the character of ancient pedagogy with teachers and disciples, recognizing that disciples maintained leadership in the earliest church (e.g., Galatians 2:9).

Much more could be said, of course, but this is a summary. Albeit in samples, we encounter real stories about Jesus and the real heart of Jesus in the Gospels.

B. J. Oropeza: The notion that the Gospels are ancient biographies is not a new concept. A few decade ago, for example, Richard A. Burridge wrote, What Are the Gospels? A Comparison with Graeco-Roman Biography (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans). What makes your book distinctive in this regard?

Craig Keener: Rather than reinventing the wheel, I take the identification of the Gospels as ancient biographies as a starting point, building on the work of Burridge and others. My working question is, what implications does this genre have for historical intention?

B. J. Oropeza: Could you provide an example or two in the Gospels on how the perspective of memory plays out in relation to ancient biography?

Craig Keener: It involves the substance of the texts rather than the verbatim words. One observation I just revisited today while working in Mark’s prologue: in John 3:24-26, John the Baptist’s and Jesus’s ministries overlap, whereas in Mark 1:14 Jesus comes into Galilee preaching once John is taken into custody. Mark, Luke, and John speak about John the Baptist proclaiming his unworthiness to unlatch his successor’s sandals, whereas in Matthew ch. 3 he is unworthy to carry the sandals. The image differs slightly but the essential point is the same, whether Matthew changed this deliberately or not.

What we would expect for eyewitnesses’ memories about a figure, and even about oral history about a figure within the period of living memory (on average, some 80-100 years), would be the core incident and maybe some details here and there. That’s why the Gospels can vary in their wording on narratives, whether about Jesus or (as in the case of parables) by Jesus. The authors of the Gospels didn’t memorize narratives word for word. They probably didn’t usually memorize teachings word for word, either, but Jesus’s aphorisms (proverbs, etc.) come much closer than the narratives do when it comes to word for word. Middle Eastern society passes on a massive number of proverbs, and ancient disciples would repeat pithy sayings of their teachers to practice remembering them. Against what some have said, this practice was not limited to particularly literate disciples; illiterate ones also practiced oral memory.

B. J. Oropeza; A relevant issue pertains to miracles, which a number of people today find difficult to accept. How does your approach in this book address the miracles of Jesus?

Craig Keener: Regarding miracles, well, I do believe in them and have written a lot about them. But having said that, the historical question as to whether the Gospels’ accounts of miracles can reflect genuine memories does not depend just on that premise. In the past, some have contended that the eyewitnesses don’t report events like these. The contenders’ opinion seems to reflect their own immediate context but is demonstrably false. Maybe these contenders are not aware of eyewitnesses in their own circles, but there are hundreds of millions of people today who report being eyewitnesses of divine healing and the like. I have interviewed people who claim to have witnessed the sorts of events we have in the Gospels, including instant healings from blindness, raisings from the dead, stilling of storms, and even walking on water (and, on a smaller scale than in the Gospels, multiplied food). (Note: See Craig Keener’s two-volume set entitled, Miracles ; Grand Rapids: Baker, 2011).

In some of these cases the external corroboration is quite strong. For example, one woman who was blind for twelve years started seeing, unexpectedly, when a minister unannounced prayed over her; everybody in the church knew her. There are other cases where I myself know the witnesses; my own sister-in-law started breathing again after three hours of being dead, as far as anyone could tell, and she had no brain damage. We have reports from doctors of patients flat-lined for 40 minutes who returned to life when someone prayed. One can dismiss these accounts as anomalies, but one cannot claim that eyewitnesses do not report such claims.

Historians dealing with figures associated with such events have to deal with such reports (e.g., Simon Kimbangu in the early twentieth century), although they are not obligated to explain them. In the case of Jesus’s ministry, miracles appear in every layer of gospel tradition: Mark, Q, John, special Matthew and Luke. They appear in Paul’s reports of his own ministry (Rom 15:19), including appealing to his own audience’s eyewitness testimony (2 Cor 12:12). They continue to be reported in early Christianity. In the late second century, for example, Irenaeus mentions a church in France where a number of people have been raised from the dead. Yale historian Ramsay MacMullen notes that the leading cause of conversion to Christianity in the 300s was healing and exorcism.

Nor was it just Christians who claimed these things. The ancient Jewish historian, Josephus (Antiquities 18.63-64) reports–in the likeliest scholarly reconstruction of the earliest text form–that Jesus was a wonder-working sage (using the same term for wonders as Josephus used for those of Elisha). Later rabbis and pagan detractors such as Celsus rejected the divine origin of Jesus’s miracles but didn’t try to deny that they happened. The strong majority of historical Jesus scholars today accept that Jesus was experienced by his contemporaries as a miracle worker, however we try to explain that.

Given the nature of memory preserved in ancient biography, then, the reports of Jesus’s miracles do not raise a challenge against miracle narratives in the Gospels reflecting genuine core memories.

B. J. Oropeza: I was just reviewing St. Augustine’s Confessions (late 4th, early 5th centuries), and in this book, too, miracles are reported, including St. Anthony’s miracles, the healing of a blind person, and interestingly enough, Augustine himself claims to have been healed instantly of a horrible toothache after his friends prayed for him.

Thank you, Craig, for your fascinating study! I’ll be back again very shortly to interview you regarding your commentary on Galatians.

Among Craig Keener’s many book include titles such as The IVP Bible Background Commentary; The Cultural Backgrounds Study Bible; Paul, Women, and Wives: Marriage and Women’s Ministry in the Letters of Paul; Miracles: The Credibility of the New Testament Accounts; and the most comprehensive commentary on the Book of Acts I have ever seen–a four volume set entitled, Acts: An Exegetical Commentary.

Image from Craig Keener (Twitter): used by permission.