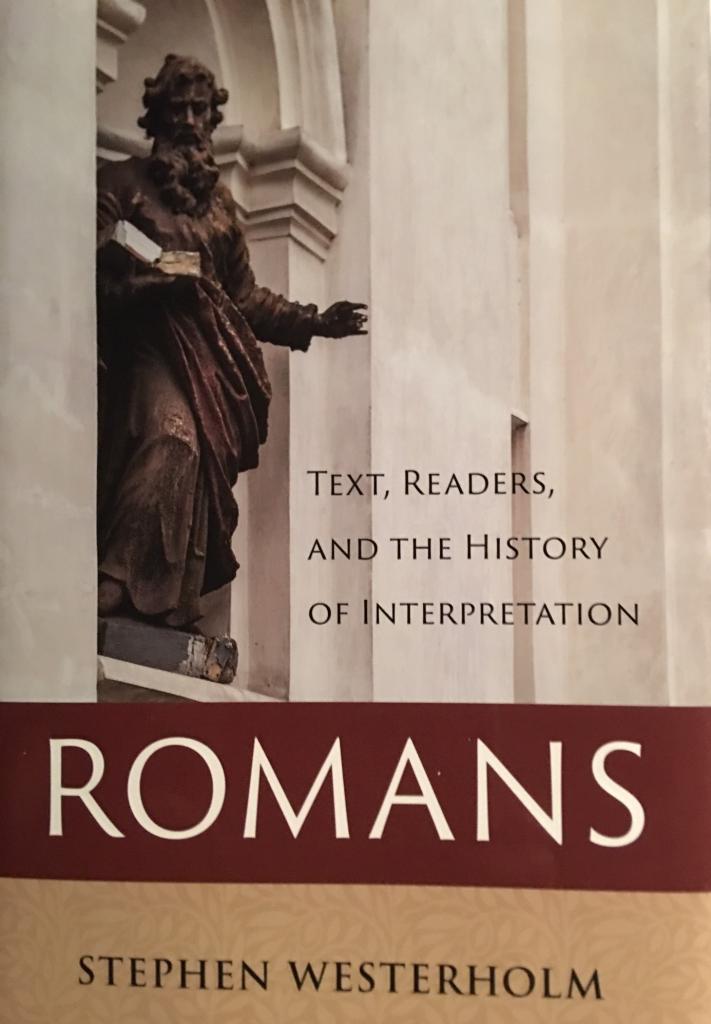

I recently had the privilege of conversing with one of the great Pauline scholars of our day, Stephen Westerholm. We discussed his new book entitled, Romans: Texts, Readers, and the History of Interpretation (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2022).This book is an introduction to Paul’s letter to the Romans that covers virtually all the past great interpreters of Romans, including Origen, John Chrysostom, Ambrosiaster, Augustine, Abelard, Aquinas, Luther, Calvin, Melanchthon, Arminius, John Locke, John Wesley, Adam Clarke, Matthew Poole, Henry Alford, Karl Barth, and a number of others! He also covers ancient Greek manuscripts on Romans, and the first readers of Romans.

Stephen Westerholm is professor emeritus of early Christianity at McMaster University (Hamilton, Ontario). He has written a number of books including great masterpieces such as the award winning Perspectives Old and New on Paul: The ‘Lutheran’ Paul and His Critics (Eerdmans, 2004) and Justification Reconsidered: Rethinking a Pauline Theme (Eerdmans, 2013). He also edited The Blackwell Companion to Paul (Wiley Blackwell, 2014), the very best anthology on Paul I have ever come across. I use this as a textbook for two of my regular courses, one an upper-division undergraduate course, and the other a seminary course.

It is both an honor and pleasure to hear from one of the truly great Pauline scholars of our day! I present several questions to Dr. Westerholm regarding his new work on Romans:

Conversation with Stephen Westerholm on Romans

B. J. Oropeza: What made you decide to write a book on the history of interpretation of Romans?

Stephen Westerholm: I never intended to write such a book. In the fall of 2012, while I was working on a project on key figures in the history of biblical interpretation (Reading Sacred Scripture, to which my son Martin also contributed), I was invited to contribute the volume on Romans for Eerdmans’ new “Illuminations” series of commentaries.

The emphasis of the series on the history of interpretation intrigued me, so I agreed—on the understanding that I would need to finish other work before I could begin the commentary. When I did begin, the only published volume in the series was the commentary on Job 1–21. It had a 248-page introduction, largely concerned with the history of interpretation.

With that in mind, I set about to write a fairly detailed history-of-interpretation of Romans, intending it to be part of the introduction to my commentary. That task took years to complete—pandemic library closures complicated the process! I turned then to the text and textual history of Romans, again as part of the commentary introduction.

At this point, I thought it wise to submit what I had written to the series editors just to let them know that progress was being made, even if I was years away from completing the commentary. They suggested, and Eerdmans agreed, that I publish what I had done as a separate volume, perhaps filling it out with another chapter or two.

Oropeza: Ah, I see! It’s sort of like my current commentary project on Romans. You write so much that it turns out to be more than one book.

Westerholm: So I prepared an additional chapter on the first readers of Romans in dialogue with “Paul within Judaism” scholars. I then included an appendix on Martyn Lloyd-Jones’s sermons on Romans (previously published in a Festschrift for Stanley Porter). It turned out to be a substantial volume in its own right.

Oropeza: You speak about the first readers of Paul and being in dialogue with the “Paul within Judaism” scholars. Could you elaborate on the connection between first readers and this perspective?

Westerholm: “Paul within Judaism” scholars see Paul as living all his days “within Judaism,” observing even the “ritual” aspects of Jewish law, and never critiquing Judaism as such.

Resisting universalizing interpretations of Romans, they see his concern, in this epistle as well as in Galatians, as limited to the issue of how gentile “sinners” could become righteous and enjoy salvation. And any negative comments Paul makes about the Mosaic law are thought to reflect its effects solely on gentiles.

Such a reading of the apostle only becomes possible if we understand his intended first readers as exclusively gentile—“Paul within Judaism” scholars insist on that point.

Oropeza: “Paul within Judaism” is one of the major perspectives on Paul these days. Magnus Zetterholm supports this view in my edited book with Scot McKnight entitled, Perspectives on Paul: Five Views (Baker Academic, 2020). Are there any reservations that you might have regarding the “Paul within Judaism” perspective?

Westerholm: There is much in this scholarship with which I agree. It is true, for example, that Paul did not see himself as founding a new “religion”—“Christianity” as opposed to “Judaism.” He thought of Christ rather as the intended fulfilment of God’s dealings with his covenant people Israel; and he interpreted the significance of Christ in light of the Jewish Scriptures and within recognizably Jewish categories.

The major weakness that I see in this group—and to which I draw attention in my book—is its failure to reckon seriously with the rethinking required by Paul’s conviction that, in God’s plan and to carry out God’s purposes, Messiah had been crucified and resurrected. If Messiah’s crucifixion and resurrection were required for human beings to be righteous before God, then the Mosaic law and covenant must have proved inadequate for the purpose—and faith in Christ and the gospel becomes the only viable path to salvation.

Once this is granted, there is no longer any need to explain away the evidence that Paul’s first readers in Rome, though predominantly gentile, included Jews as well.

Oropeza: Back in 2005 Mark Reasoner wrote a book entitled, Romans in Full Circle, which was sort of like a history of interpretation beginning with Origen’s commentary on Romans. Reasoner suggests that the theological trend related to Romans has moved in a circular direction throughout history; the trend in our own era is once again resembling Origen’s views. In your own book, which interpretative trend(s), if any, have you noticed regarding Romans throughout the centuries?

Westerholm: I am no expert on church history, but I know enough that I wasn’t surprised by any of the interpretative trends I came across.

What was of interest was noting how developments in church history impacted the interpretation of particular passages in Romans. How, for example, early Greek commentators used Romans to respond to gnostic beliefs; the subtle scholastic distinctions with which Aquinas resolved exegetical issues; how disputes between Reformers and Catholics affected their readings of a number of texts (not simply those dealing with justification!); how the rise of liberal Christianity impacted the interpretation of Romans in such figures as Benjamin Jowett and John William Colenso. Exegesis and theology have always gone hand-in-hand!

Oropeza: What are some new and interesting discoveries you came across in Romans while working on this book?

Westerholm: As far as Romans itself is concerned, perhaps I can just mention a fascinating reading, repeatedly encountered, of Romans 5:13: that sin was not “counted” before the law was given is all but invariably interpreted today as referring to God’s not “counting” sin (in some sense) before Moses. This is an interpretation not without its difficulties. Early interpreters frequently understood Paul to refer to human beings (rather than God) who failed to take sin seriously apart from the law—a reading accompanied by issues of its own, but by no means without interest.

As far as the history of interpretation of Romans is concerned, I cannot begin to list “new and interesting discoveries.” A number of interpreters about whom I wrote were little more than names to me before I began the study. (I don’t think I had even heard of Augustin Calmet or John Taylor, though they were important figures in their time.)

I deliberately expanded the list of those I would consider beyond the “usual suspects” to include people like Philipp Jakob Spener, Richard Baxter, John Locke, and Cotton Mather. They are well-known names but not usually associated with biblical interpretation, though they all commented at length on Romans. What they have to say is always worth consideration.

I also devoted a section to early English translations of Romans: Wycliffe, Tyndale, the Geneva Bible, the Rheims New Testament, and a few notes on the King James Version. I can only hope that readers share something of the fascination I felt in discovering old ways (but new ways to me) of reading Romans.

Oropeza: Your history of interpretation covers patristic, medieval, sixteenth century, and modern period of Romans interpreters up to Karl Barth. The modern period includes 14 different names plus several more you have listed under the heading of “Arminian interpreters.” Minus Barth, who would you say are your favorite interpreters? In other words, who would you first recommend to your students and fellow scholars to read?

Westerholm: I wrote about a number of “modern” interpreters, but several are excluded at once from being recommended reading, simply because their work is not readily accessible. For readers concerned with the details of Paul’s vocabulary or grammar, I would probably recommend Henry Alford, or even more so Heinrich August Wilhelm Meyer. This recommendation comes with the caution that they should be read together with a good modern commentary, since our understanding of Koine Greek has progressed a good deal since the nineteenth century.

Also, perhaps Alford, Matthew Poole, and Adam Clarke warrant reading for their practical insight into the epistle. With several other interpreters (e.g., Locke, Mather, Gill, Jowett), one reads them more to learn about the interpreter than because one expects unique insight into Paul’s text. But every commentary contains its surprises!

Oropeza: What would you consider to be the central theme (or themes) in Romans?

Westerholm: I am reluctant, I must say, to identify a particular emphasis in Romans as “the central theme,” especially since I am still in the early stages of preparing a commentary on the epistle! The universal need for the gospel is obviously of great importance in the early chapters, as is Paul’s concern in stressing universal need—to say that this applies to Jews no less than gentiles. It would be hard to find an interpreter, from Origen to the beginnings of the “Paul within Judaism” movement, who failed to recognize these points.

Similarly, it escapes no one’s attention that Paul devotes Romans chapters 5–8 to different aspects of Christian living, partly in response to criticisms he received elsewhere (see Romans 6:1, 15).

For some readers, Romans 9–11 are thought to deal primarily with predestination, but no one fails to take note of Paul’s concern with Israel’s continuing place in God’s plan, which is the real theme of these chapters.

Still, I am hesitant to adopt what seem to me to be overly schematized readings of the epistle. I doubt, for example, that Paul intended Romans 1:16-17 to be seen as providing the structure of the entire letter.

Oropeza: Were there any interpreters that you found particularly helpful with regard to these observations?

Westerholm: Although I, of course, find certain interpreters more helpful than others on specific passages, it hasn’t occurred to me that any particular interpreter can serve as a consistent guide to the true interpretation of the epistle—almost all are helpful at some point. I should perhaps add that novelty in interpretation holds no attraction for me.

Oropeza: Why do you think Paul wrote this letter?

Westerholm: Everybody recognizes that Paul writes to prepare the Romans for a visit he intends to make after his trip to Jerusalem; and that, at various points, he responds to criticisms he has encountered in the past and wants to forestall in Rome.

Many think Paul’s discussion of those “weak” and “strong” in faith in Romans 14–15 represents a response to tensions among believers in the city. And broadly speaking, Paul sees the Roman believers as within his sphere of responsibility as “apostle to the gentiles.” In that regard, there need be nothing specific to the Roman situation in his setting forth what he sees as the true nature of the gospel and the kind of life that it requires of believers.

Beyond these points, proposals have of course been made that are largely or entirely speculative. But to my mind it is perilous to interpret the letter on the basis of a speculated reason for its writing.

With or without a connection with conditions in Rome, it seems clear that Paul takes the opportunity to sum up in this letter his responses to problems he had encountered in other churches. The early chapters, dealing with justification, are very reminiscent of Galatians. When he speaks in Romans 12 of different gifts given to believers, we are reminded of 1 Corinthians 12. His treatment of those “weak” and “strong” in faith recalls 1 Corinthians 8.

Oropeza: Any final comments about Romans?

Westerholm: Beyond all this, it does seem to me that Paul takes the opportunity of this letter to record his mature thinking on issues with which he had himself wrestled. For example, his treatments of the law in Romans 7 and especially of Israel in Romans 9–11 transcend by far what might have been required to answer questions the Romans might have had on the subjects. They are topics on which Paul must have reflected a great deal for his own “peace of mind.”

Romans is far from a systematic theology; but for good reason it plays a central role in any reconstruction of Pauline theology. Though Paul was moved by a particular occasion (his immediate plans) to write the epistle, much in the epistle seems far from occasional.

In so reading the Romans epistle, I am, of course, reading it along “traditional” lines; the evidence, I believe, requires it.

Oropeza: This has been a stimulating discussion! Thank you for your time, Stephen. I, and many others, I’m sure, look forward to reading this book and also your upcoming Illuminations commentary!

* * *