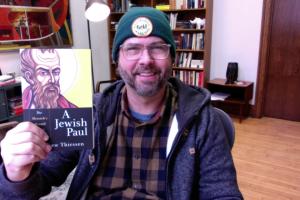

We are back for Part 2 of our interview with Matthew Thiessen! Dr. Thiessen recently wrote, A Jewish Paul: The Messiah’s Herald to the Gentiles (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2023). In Part 1 we discussed this book’s relation to Dr. Thiessen’s earlier work, Paul and the Gentile Problem, Paul’s weirdness, and the interpretation of Paul’s phrase, the “works of the law.” This instalment compares Paul in Acts with Paul in his letters in relation to the law, the translation of “Judaism” in Galatians 1:13, and more:

A Jewish Paul: The Interview, Part 2

Oropeza

You do a good job of showing that Paul is a law-abider in Acts (e.g., Acts 21:23–24; 25:8; 28:17), and I agree with you that Luke portrays Paul as law-abiding—he is innocent of the charges against him.

Paul’s letters, however, pose a different challenge. He speaks in the first-person plural not only to but with gentiles about “our freedom in Christ” in the context of maintaining Titus’s foreskin/uncircumcision in Galatians 2:4. Then there’s Galatians 2:21; 2 Corinthians 3, and so on. Is it possible that, in Christ, Paul himself has the freedom to keep and not keep aspects of Mosaic law depending on the company that he keeps?

Thiessen

One of the challenges in seeking to recover Paul’s thinking about the Jewish law is how to deal with the apparent discrepancy between Acts and Paul’s own letters. Historians rightly argue that one must trust the primary evidence of Paul’s letters over the secondary evidence of Acts when reconstructing Paul’s own thinking.

So, if Acts and Paul disagree, we must trust Paul here. I agree with this, but question whether we have understood Paul correctly here. Paul’s letters seem more difficult to understand than the narrative of Acts. Maybe we’ve just misunderstood Paul!

Oropeza

That’s both the challenge and excitement about interpreting Paul!

Thiessen

But there is one thing that both Paul and Acts clearly agree on—humans are not justified by the observance of the Jewish law. We see this at numerous points in Paul’s letters, including Galatians 2:21 which you mention, and also in Paul’s speech in Acts 13 (vv. 38–39). And in 2 Corinthians 3 (cf. Gal 3:21), Paul makes it clear that the law, glorious and good as it is, does not give life to the dead. That’s not the function or purpose or power of the law, but that doesn’t mean it doesn’t have an important role. Obviously in Luke’s narrative, Jewish followers of Jesus, including Paul, are still supposed to and do follow the law.

When it comes to Paul’s own claims, we don’t have any obvious statements one way or another in my mind, so we need to extrapolate from other things he says. And this, while necessary, can become an opportunity to import our own assumptions. I think one assumption that is easy to import is our generally negative view of law—law as something that unnecessarily restricts or harshly condemns. Is this how ancient Jews viewed the law? And is this how Paul viewed the law?

The “we” in Galatians 2:4 might suggest that both Paul and gentiles (and everyone?) are free from aspects of the Jewish law. But the only thing we know for sure in this verse is that Paul does not think gentiles are constrained by the Jewish commandment to undergo circumcision, and he is not constrained to tell them that they should be. But this wasn’t a unique legal position in ancient Judaism. Many, perhaps most, ancient Jews didn’t think the Jewish law applied to non-Jews, so there was no need for gentiles to undergo circumcision.

Oropeza

I’m reminded of the competing views on whether King Izates, a gentile who worshipped the Jewish God, should also be circumcised. For the merchant Ananias, the answer was no, and for Eleazar, it was yes (Josephus, Antiquities XX.2.3–5 [§34–53]; cf. XX.1.1 [§17]).

Thiessen

Did Paul feel himself free to keep or not keep aspects of the Mosaic law depending upon who he is with? This is often how people have read Paul’s statements about adaptability in 1 Corinthians 9:19–23.

But I wonder just how elastic we are to imagine Paul’s behavior here. I find it historically implausible and morally reprehensible that Paul could have acted like a law-observant Jew to try to impress or win over Jews, but abandoned law observance around gentiles to try to impress or win over gentiles. Were Christians to imagine anyone other than Saint Paul doing something like this, I can’t help but think that we would conclude such a person was deeply deceptive and hypocritical behavior.

Oropeza

Paul, I think, would agree that adaptability or accommodation should never resort to hypocrisy. He comes against flattery and being disingenuous (Gal 1:10; 1 Thess 2:5; 2 Cor 1:12).

The way I read 1 Corinthians 9:19–23 is like this—in the same context (1 Cor 8–10), Paul charges certain Corinthians to give up their “right” or exousia over what they eat to accommodate weaker brothers and sisters who might see them eating idol foods and it become a stumbling-block to them. Adaptability in this case is so that their faith/trust does not get ruined (1 Cor 8). It is for the purpose of “saving” or keeping the weak saved. Adaptability, then, should be for the sake of not becoming the cause of stumbling to Jew, Greek, or the ekklesia of God (1 Cor 10:32). Paul does not want to seek his own advantage (symphoros) but the advantage of many, so that they might be saved (1 Cor 10:33). (On 1 Cor 8-10, cf. my 1 Corinthians commentary).

New subject: On pages 40-41 of A Jewish Paul, I want to thank you for not blaming the translators of NRSVue regarding their translation Galatians 1:13–14. The reason? I was on that translation team for Galatians!

Like you, I struggle to understand Ἰoudaismos, translated in Gal. 1:13 as “Judaism” (NRSVue, and this was not my choice for its translation). The term should be qualified in some sense as pertaining to the way Paul used to be prior to his Damascus experience. It is not that he is abandoning being a Jew. I’m open to suggestions for how to translate the Greek word in the future. Do you have any recommendations?

Thiessen

On the surface, Ἰoudaismos looks like it should be easy to translate—it just looks so much like “Judaism”! But it is such a rare word, appearing only several times before it appears in Paul (2 Maccabees 2:21; 8:1; 14:38; and 4 Maccabees 4:26). In that body of literature, it stands in contrast to Greek and foreign practices being imposed upon Jews by Greeks. My hunch is that the term Ἰoudaismos was coined in the second-century BCE in opposition to the widespread pattern of hellenismos, the adoption of Greek customs by those who were not Greek.

Whatever the precise connotation in Galatians, I agree with you that it should be read to mean not that Paul has abandoned something called “Judaism” for something called “Christianity,” but that he has changed his Jewish way of living from one form, that shaped by the ancestral customs of the Pharisees, to another, that shaped by the belief that Jesus was the Messiah and had been raised from the dead.

Oropeza

I’ve toyed with the translation in the relevant portion of Gal 1:13 as, “former conduct in the Jewish way” (… ἀναστροφήν ποτε ἐν τῷ Ἰουδαϊσμῷ), but even that does not seem to be specific enough.

Thiessen

I think that Paul’s former way of life can perhaps be defined a bit more precisely. The noun Ἰoudaismos is etymologically related to ioudaizein (“to judaize”), which means “to act Jewish” or “to adopt Jewish customs.”

And something Shaye Cohen has convincingly argued is that -izein verbs indicate the action of one person or group adopting the customs of another group. Jews don’t judaize, only non-Jews do. So, I have tentatively suggested that when Paul talks about his former way in Ἰoudaismos here, he is referring to his previous efforts to get non-Jews to adopt Jewish customs.

And we see Paul’s acknowledgement that he did at one point in time promote judaizing to gentiles in his statement, “If I still preach circumcision” (Gal 5:11). Now though, he rejects this program and condemns efforts to encourage or compel gentiles to “judaize,” as one can see in his harsh words to Peter in Gal 2:14.

* * *

Coming next: Part 3 of this Interview…