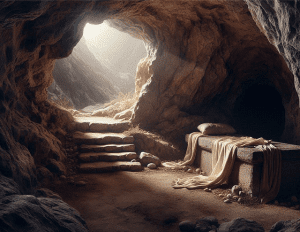

Paul’s omission of Jesus’s empty tomb, found in the Gospels, is a peculiarity sometimes pointed out regarding his resurrection statements. One of Paul’s clearest statements on his gospel and the resurrection of Jesus is 1 Cor 15:3–4. Here he writes, “For I delivered to you among first things what I also received: that Christ died for our sins according to the scriptures, and that he was buried and that he rose on the third day according to the scriptures.”

The importance of this belief statement cannot be overemphasized. This is one of the earliest written affirmations of the resurrection. Paul writes this letter about 55 CE, just about 25 years after the actual death and resurrection of Jesus. None of the Gospels had been written yet, and at that time very few New Testament documents existed. Prior to 1 Corinthians the only other letters that had been written already were Galatians and 1 Thessalonians (also 2 Thessalonians for those who consider it authentic).

Does omission of the empty tomb suggest that Gospel testimonies were a later development created by the church?* Does this suggest that Paul did not believe in the bodily resurrection of Jesus?

Such postulations are not only arguments from silence but they also stand at odds with oldest evidence that we do have.

The Burial of Jesus as Evidence for an Empty Tomb

Paul’s mention of Christ’s burial in 1 Cor 15:4 would seem to be sufficient enough to assume an empty tomb for the Corinthians, Paul’s original audience. They were already familiar with the gospel about Christ’s death and resurrection that Paul proclaimed among them when he stayed with them (eighteen months if Acts 18:11 is correct). Paul makes it clear that they already believed and received this gospel message (1 Cor 15:1–2; cf. 2:1–2).

Hence, when Paul writes that Jesus “died… and that he was buried,” this statement stands as the prerequisite to resurrection. Given that the resurrection is also mentioned in 15:4, Jesus’s burial assumes Jesus was laid in a tomb and then vacated it after he rose again. This is similar to what we find later in the Gospels, even though our apostle does not mention the words, “empty tomb.”

Paul will also continue to explicate the nature of resurrection as bodily with continuity between the body laid and body raised (see 1 Cor 15:35–49 and further, B. J. Oropeza, 1 Corinthians, NCCS (Eugene: Cascade, 2017: 196–223).** The inference would seem clear enough that after Christ rose from the dead, the place of Christ’s burial was no longer occupied with his physical body. Hence, for Paul to mention an empty tomb in this brief summary would be redundant. (On this point, see further, N. T. Wright, The Resurrection of the Son of God, 321).

Kerygma and Narrative

As James Ware shows, before and even long after the Gospels were written, there was no early Christian creed or kerygma (proclamation statement) inclusive of the empty tomb for roughly two hundred years.*** What we do find is a pattern similar to Paul’s belief statements that mention Jesus’ death, burial, and resurrection, or simply Jesus’s death and resurrection (e.g., Acts 10:36–41; 17:31; 1 Peter 3:18–22; Ignatius Smyrnaeans 1.1–2; Trallians 9; Justin Apology 1.21.1).

This is obviously not because the Gospels had not been written yet—John’s Gospel, the last of the four, is normally dated towards of the end of the first century. Rather, these creed-like formulae presupposed further narratives that informed early Christian audiences—first orally, then in written form—about the details related to the Lord’s supper, arrest, trial, crucifixion, death, burial, and resurrection appearances of Jesus. The same would seem to be the case with Paul’s gospel.

Birger Gerhardsson’s point about this says it well:

“Elementary psychological considerations tell us that the early Christians could scarcely mention such intriguing events as those taken up in the statements about Jesus’ death and resurrection [such as in 1 Cor 15:3-8] without being able to elaborate on them. Listeners must immediately have been moved to wonder and ask questions. Regarding our text there must have existed in support of the different points in the enumeration [of 1 Cor 15:3–8] . . . narratives about how they came about. Our text . . . cries out for elaboration,”****

Burial of the Crucified

We need not assume that Jesus’s body was not buried due to the Romans or Pilate not permitting the burial of crucified corpses. Yes, some crucified corpses were not granted burial—and such might be left to rot or be eaten by birds and dogs (Valerius Maximus 6.2.3; Horace, Epistles 1.1.6.46–48; Apuleius Metamorphoses 6.32.1). But others were placed in burial pits, and some corpses were granted burial for other reasons (e.g., Cicero In Verrum 2.17; 2.5.134; Philo Flaccus 83; further, John Granger Cook, Crucifixion in the Mediterranean World. WUNT 327. Tubingen: Mohr-Siebeck, 2014: 66, 111, 187, 385–87, 429, etc.).

Jews were also known to provide burial rites for criminals and those crucified (Josephus Bell. 4.317; Cook, 239).

Roman clemency was such that its law could permit the burial of those who had been executed (Digesta 48.24.1, 3). Roman magistrates after Agrippa I, according to Josephus, did not compel their subjects to disrupt their own respective laws and customs, including burial of corpses (Josephus, Apion 2.73, 221; Jewish War 2.220). (See further, Craig A. Evans, “Getting the Burial Traditions and Evidences Right,” in How God became Jesus, ed. Michael F. Bird, et al., Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2014: 71–93.)

Jesus’s Burial

Pilate, though at first attempting to violate Jerusalem’s standards by bearing images, backed down from doing so after learning how loyal Jews were to their laws (Josephus, Ant. 18.55–59). In this light, as Craig Evans rightly suggests, it is unlikely Pilate or other Roman governors of Israel in the early decades of the first century would leave the bodies of crucified criminals unburied and thus defile the land. This would be contrary to Jewish law that required that the burial of criminals take place before sunset (Deut 21:22–23; Josephus Jewish War 4.317; 11Q19 64.7–13; Mishnah Sanhedrin 6.5; Evans, 78–86). The crucified remains of Yehohanan, a Jewish man whose remains were found in an ossuary tomb at Giv‘at ha-Mivtar, attests to this.

That Joseph (in all four Gospels) was permitted by Pilate to bury Jesus before sunset is entirely consistent with such practices.

In sum, for Paul, Jesus’s burial assumes he was laid in a tomb. That he rose again bodily from the dead thus assumes an empty tomb.

Notes

* As for example, Gerd Lüdemann in Jesus’ Resurrection: Fact or Fiction? A Debate Between William Lane Craig and Gerd Lüdemann, eds. Paul Copan and Ronald K. Tacelli (IVP, 2000), 44.

** On bodily resurrection in this passage, see also, James Ware, “Paul’s Understanding of the Resurrection in 1 Corinthians 15:36– 54.” Journal of Biblical Literature 133 (2014), 809–35.

*** James Ware, “The Resurrection of Jesus in the Pre-Pauline Formula of 1 Cor 15:3–5,” New Testament Studies 60 (2014) 475–98, here 480–81.

**** Birger Gerhardsson, “Evidence for Christ’s Resurrection According to Paul,” in Neotestamentica et Philonica: Studies in Honor of Peder Borgen, ed. David E. Aune, et al, Leiden: Brill, 2003), 75-91, here 89). Italics mine.