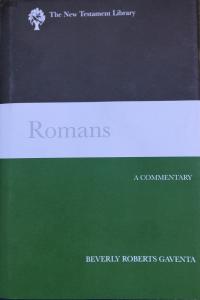

I have the privilege of interviewing Beverly Roberts Gaventa on her new commentary on Romans. As many already know, Dr. Gaventa is one of the foremost authorities on Romans and the apocalyptic Paul. She is Helen H. P. Manson Professor Emerita of New Testament Literature and Exegesis, Princeton Theological Seminary. She also held the position of president of the Society of Biblical Literature (2016), and she received the Burkitt Medal for Biblical Studies from the British Academy, due to her many distinguished contributions to New Testament scholarship (2020).

Some of her distinguished works include, When in Romans: An Invitation to Linger with the Gospel according to Paul (Baker Academic, 2018); Apocalyptic Paul: Cosmos and Anthropos in Romans 5–8 (Baylor University Press, 2013); Our Mother Saint Paul (Westminster John Knox, 2007); Mary: Glimpses of the Mother of Jesus (Augsburg Fortress, 1999), and commentaries on 1–2 Thessalonians for the Interpretation series, and Acts for Abingdon New Testament Commentaries.

And now her latest work is a comprehensive commentary entitled, Romans written for The New Testament Library series (Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press, 2024).

The Interview

Oropeza

You are well-known for your apocalyptic view of Paul. For our audience’s sake, could you provide us with some of the basic features of the apocalyptic Paul?

Gaventa

In Our Mother Saint Paul, I wrote that “Paul’s apocalyptic theology has to do with the conviction that in the death and resurrection of Jesus Christ, God has invaded the world as it is, thereby revealing the world’s utter distortion and foolishness, reclaiming the world, and inaugurating a battle that will doubtless culminate in the triumph of God over all God’s enemies” (p. 81). This involves human liberation, receiving the gift of the Spirit, and being grafted together into the body of Christ.

I am largely content with that statement, although today I would amplify what is meant by “invasion.” While the word does justice to some of Paul’s language, it neglects the radical extent to which God’s power differs from human notions of power.

God’s power looks a lot like the weakness of the cross, to begin with. And that statement also suggests that Paul’s apocalyptic means a dramatically different way of thinking about the world.

Oropeza

What are some significant ways that your apocalyptic reading of Paul enlightens your interpretation of Romans?

Gaventa

I would want to flip that question. My reading of Romans shapes and reshapes my apocalyptic interpretation. Crucial for me is the statement in Romans 1:16 that the gospel is the apocalypse of God’s power. God’s power—again, a rescuing (saving) power—runs throughout the letter, as I understand it.

I think that focus on God’s rescuing initiative helps especially when we come to Romans 9–11. Otherwise, the interpretation gets tangled up in Paul’s developing comments about Israel (and it often neglects his critique of gentile arrogance).

Oropeza

I like your focus on the notion of God’s rescuing power from Rom 1:16, a text that I and many others consider to be part of Paul’s guiding thesis for much of the letter.

What do you consider to be the purpose of Romans? Why, or what primary reasons, did Paul write this letter?

Gaventa

I don’t think any single purpose accounts for the whole of the letter. At the outset he indicates he intends to preach—i.e., declare the good news—for those in Rome, and the letter begins that undertaking. But he also wants their prayers for his trip to Jerusalem, which is clearly a source of serious concern (Rom 15:25–32).

Oropeza

I agree with you that there is more that one purpose to this letter. Now that I finally finished the first (rough) draft of my own commentary on Romans, I see that more clearly than ever. My view will be in print in another year or so in an article entitled, “The Purposes of Paul’s Letter to the Romans: Moving the Debate Forward,” where I engage with some of the scholars in Karl Donfried’s The Romans Debate (2nd ed. Peabody: Hendrickson).

And speaking of debates, I’m sure you are well aware that there is a controversy regarding the audience’s identity in Romans. A number of scholars claim it’s a mixed audience of Jews and gentiles, or a mostly gentile audience. Although some have argued for a Jewish audience (e.g., Steve Mason), a recent trend argues for a purely gentile audience (e.g., Stanley Stowers, Runar Thornsteinsson, Andrew Das, William Campbell, etc.). Where do you stand on this issue?

Gaventa

The audiences (plural) contain both Jews and gentiles, as seems clear from the names in chapter 16 and various points within the letter. But it’s important to recognize that most of these gentiles come from the ranks of those already attracted to the synagogue—or at least to features of Jewish life.

Oropeza

I concur. And regarding Romans 16, I don’t think it works to argue as some do that Paul’s imperatival use of greetings suggests that those whom he greets were not among the hearers of this letter. An often-overlooked point is that Paul also says to greet Mary among the many names in Romans 16. She labored for them—that is, the recipients of this letter (Rom 16:6). The reason Paul could say this is because she belonged to the same Christ-community as the auditors hearing this letter in Rome (I will be expanding on this point in an upcoming article and my commentary).

You bring out a number of insights in this work. What would you consider to be one of the most important points that you would want your readers to learn from your commentary?

Gaventa

One of the things I learned from working on the commentary was its preoccupation with worship, by which I mean human reverence for God, human life that begins with an acknowledgement of its status as created rather than Creator. I see that not just in Romans 1, but in the catena of Romans 3, the liturgical language of 12:1, and in numerous doxologies and Amens.

I would hope readers would find that feature of the letter a helpful orientation to the rest of the letter.

Oropeza

Thank you for your time and insights, Beverly!