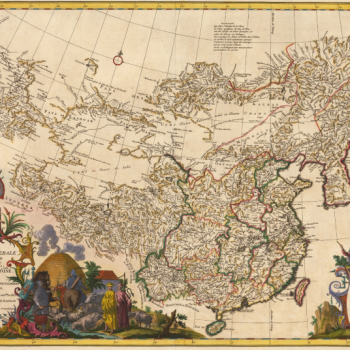

The Chinese religious scene is nothing if not adaptable. This is nowhere truer than in the field of eschatology. As I have discussed at length previously, China’s basic apocalyptic narrative is an old one and many of its core elements have remained recognizable for two thousand years. Every so often, however, the sphere of Chinese religion undergoes a seismic shift. A new element comes into play. It does not displace the old system—no idea ever seems to be wholly displaced in China—but forces that system to adapt, evolve, and accommodate new concepts and symbols without losing its basic form and structure.

If Chinese religion is the macrocosm, the microcosm is China’s apocalyptic narrative, which has perfectly encapsulated this process through the centuries. Wang Mang championed a particularly Confucian version of it, but when his attempt to introduce a millennial kingdom of sagely government fell apart beneath him, Taoist symbols and phrases came to dominate the popular end-times narrative instead of Confucian ones. These symbols, while never disappearing entirely, were largely pushed to the side when Buddhism gained traction in the country during the fifth and sixth centuries. The standard account of the end-times became a Buddhist one, with the future Buddha Maitreya taking the messianic role once reserved to the Taoist savior Li Hong, even as the most orthodox of Buddhists sneered at the very idea of a coming apocalypse. And so, for a very long time, the primary symbols and terminology of the end-times narrative remained Buddhist, even as the apocalyptic beliefs underpinning it drifted further and further away from Buddhism. But recently, another shift has been occurring, one whose consequences will only be fully grasped in the centuries to come. The monumental event driving this shift is the entry of Christianity into the country and its infiltration into the ranks of popular religion. Now, when someone encounters apocalyptic thought in China, they are very likely to find that it is not Maitreya but Jesus who is expected as the messianic ruler of the future age.

And yet, the old narrative structure, with its characteristic plotlines and archetypes, has remained intact. Often, it feels as though, across two millennia, that only the names have changed to accommodate whatever religion currently holds the most sway in Chinese society. And most recently, to the extent that any religion can be said to have a leg up in what is still officially an atheist country, that religion has been Christianity. Christianity’s rapid expansion in China has been a source of puzzlement for observers given that the faith is on the decline in so many other places. But, while it does not explain the trend in full, part of the reason for Christianity’s modern success in China probably lies in how amenable it is to the country’s long-established undercurrent of apocalyptic belief. Apocalyptically-minded groups have usually been the first to gravitate toward Christianity in China, no doubt because the Christian end-times story is so much like the one they know. It is particularly easy for them to simply cover up the Buddhist symbols and names with Christian ones, while leaving the eternal apocalyptic narrative largely intact.

As we have seen previously, this is because Christianity’s apocalyptic narrative, while is not identical to the Chinese one, is eerily similar in many respects, with certain themes and symbols reappearing in both. It does not take much for apocalyptic sectarians to learn to call the floating city “New Jerusalem” instead of “Huacheng” or the northern barbarian hordes “Gog and Magog” instead of “Guyue,” when the underlying symbols themselves seem to be basically the same. In short, apocalyptic Christianity found the ground well-prepared for it by the indigenous apocalyptic narrative and has benefited much from how firmly entrenched that narrative is in the Chinese cultural landscape. Though perhaps this has come at a price, as Christianity now seems to simply be the newest graft on an eschatological system that long predates it in China and which will no doubt continue to maintain its grip on the China’s apocalyptic imagination regardless of Christianity’s own future fortunes in the company.

Still, occasionally, something wholly new does find its way into the long-established eschatological scheme. The concept of the three ages, as used by sectarian groups from the Ming Dynasty onward, was one such completely new element. Prior to its appearance in the Huangji jieguo baojuan of 1430, there is no trace of it in the Chinese apocalyptic tradition, leaving a perplexing puzzle as to where it came from. Scholars of Chinese religion have traditionally tried to explain it away as an outgrowth from one of three preexisting ideas in the China’s syncretic religious landscape. These are the creation-fall-redemption world-narrative found in faiths such as Manichaeanism, the concept of the three stages of the dharma as found in orthodox Buddhism, and Taoism’s notion of the three yuan. I have looked at each of these ideas in some detail previously and shown why they cannot be the ultimate source of the sectarian Three Ages idea. But it might be useful here to consider in more depth why each of them could not have formed the basis for the Three Ages concept of later sectarian thought. Afterward, we will spend the rest of this entry reviewing our findings so far so that we are properly prepared for the final part of this series, which will detail the later interactions between Christianity and the Three-Ages sects in China.

Let us start with the creation-fall-redemption narrative world narrative. Scholars such as Susan Naquin were once quick to assert that Manichaeanism was the source of the sectarian Three Ages system because it had a similar structure of time divided into three periods. But this is not true. Manichaeanism’s cosmological narrative begins before creation when the forces of light and dark, good and evil, are properly separated. Their admixture then creates our fallen, imperfect world. Someday, the world-prison will cease to be and light and dark will be properly separated once more. Scholars of religion once chose to interpret these three stages as three temporal periods. In their reading, the Manichaeans taught that world history itself is divided into three periods of time. From there, they could connect those supposed time periods to the ones the later sectarians believed in.

The cosmological narrative employed by syncretic sectarian groups of the Ming and post-Ming periods does resemble the one found in Manichaeanism if you look at it it hard enough. They believed that humanity (or the supernatural beings that would become humanity) lived in an original purity in heaven and on earth. However, they became corrupted by sin and desire, which prevented them from transversing freely between heaven and earth and trapped them in this world. In the future, however, humanity—or at least a chosen elect—will escape their earthly shackles and return to the heavenly paradise. This narrative can be said to follow Manichaeanism’s basic story beats. But at the same time, these same narrative steps of primordial bliss, fall into sin, and eventual redemption are common to many world religions, including Christianity. That the sectarian belief system also has them does not indicate any sort of connection to Manichaeanism, and scholars have yet to find anything within the sectarians’ conception that can be labeled as distinctly Manichaean. Indeed, trace of the purity-fall-redemption narrative can be found in Chinese apocalyptic thought long before Manichaeanism made its entry into China.

But even more damaging for this theory than the demonstrable lack of Manichaean influence on sectarian beliefs is the fact that no one who propounded the purity-fall-redemption narrative thought of those three steps as constituting three separate periods of time, not the Manichaeans nor the Christians nor even the sectarians themselves. For the Manichaeans, the original separation of good and evil and their final separation both take place outside of time. The lifetime of the world and the cosmos, the span of history, fit entirely into the stage of the fall. Christianity and the sectarians also understand things this way. Historical events—particularly the work of guiding believers to salvation—might lead to the final stage beyond history but the glorious culmination of redemption, the “new heavens and new earth,” still stand beyond the existence and lifespan of our world.

By contrast, the three ages as conceived by the sectarians are very much within time and the history of this world. Indeed, they constitute the entire lifetime of our world and cosmos, as distinct from the heavenly purity that both existed before the world’s creation and will be all that remains after its end. The ages do not extend beyond our universe’s temporal boundaries. The baojuans are very clear about this. The sacred texts of the sectarians make a distinction between what they call the xiantian (先天—former heaven) and the houtian (後天—latter heaven). The xiantian or “former heaven” refers to what Westerners might simply call “Heaven.” It is the eternal abode of the Unborn Mother / Primordial Buddha and the original home of all the souls that became humans. The former heaven existed before the world and cosmos were created, exists today beyond their boundaries, and will continue to exist after the world and universe have ceased to be. Returning there—either after death or at the universe’s end—is the final hope of all believers.

The former heaven, then, corresponds to the “original purity” and “final redemption” stages of the model outlined above. It is completely beyond time. The houtian or “latter heaven,” refers to our own world, which began at the moment of creation and which will someday pass away. All of historical time lies with this “latter heaven” and it corresponds to the stage of fallen existence outlined above. Crucially, the three ages are only ever applied to the progress of time within the latter heaven and never to anything related to the former. They are a phenomenon existing entirely within the latter heaven and historical time, acting as the temporal field in which the process of salvation can play out. The former heaven, being the destination of the already-saved, has no need for them. Thus, the baojuans make a sharp distinction between the three time periods and the larger fall-and-redemption narrative that undergirds their cosmology.

This is why the Longhua jing, which has the last age begin with its own original author Gongchang, portrays the final moment of redemption as happening after the world and the last age have ended, stating, “After the end there will be a Dragon-Flower Assembly, when all buddhas and patriarchs together return to the root” (qtd. in Seiwert 375). Because salvation is only complete when a soul enters the former heaven beyond time, the entry of all the saved into perpetual bliss can only happen after time itself and its constituent ages have ceased to be. Since the sectarians themselves are so insistent that the Three Ages are different from the larger narrative of purity, fall, and redemption—even as they play the decisive role in bringing the progression of that narrative to its conclusion—we must also accept that the Three Ages are a unique development and not simply a transformation of the three major steps (purity, fall, redemption) in that wider narrative structure.

We could make a similar case against deriving the three ages from the three stages of the dharma or from the three yuan. But first, let us consider these ideas in more depth, starting with the three dharma periods. Seeing the Three Ages as simply a modified form of the dharma stages has long been popular among scholars. Indeed, Hubert Seiwert himself subscribes to the idea, as seen in Popular Religious Movements and Heterodox Sects in Chinese History, where he states, “The idea of three cosmic periods associated with the three Buddhas of the past, the present, and the future, and of catastrophes at the end of great kalpas had its precedent in orthodox Buddhism” (Seiwert 443). But this is not true. While it is true that the later notion of the Three Ages had much Buddhist symbolism attached to it, the only orthodox Buddhist concept of three temporal periods, was that of the three dharma stages, which had a completely different character.

In orthodox Buddhism, the three dharma periods are the zhengfa (正法—true dharma), xiangfa (像法—semblance or counterfeit dharma), and mofa (末法—final dharma). The time of zhengfa, of the true dharma, begins with the preaching of the faith by Siddhartha Gautama, the Buddha of our current dispensation, and continues with the efforts of his first disciples to spread and codify his teachings. During this era, the Buddhism faith is in a pure and uncorrupted state, the body of believers is united, and it is easy to encounter the Buddha’s teachings in a complete and uncontaminated form. In the following xiangfa period, that of the semblance dharma—which is usually defined as our current time—corruption has wormed its pernicious way into the faith. Buddhist institutions are compromised, monks and teachers fail to live a pure and devout life, and the body of believers is divided. It is now difficult to encounter the teachings of the Buddha in a full or uncorrupted form and, as a consequence, following his true teachings and the path to enlightenment is now much harder. After this comes the mofa, the final era of the dharma, when corruption overcomes the faith entirely. Buddhist institutions fall, the teachings are forgotten, and Buddhism as a religion goes extinct. It becomes nigh impossible to encounter the teachings of the Buddha and find enlightenment. This deplorable state of affairs lasts for many aeons until Maitreya appears on earth to reveal the true teachings of Buddhism once again.

This is a very different concept from the later sectarian understanding of the Three Ages of time. Indeed, the only thing the one shares with the other is a basic division of some span of time into three periods. But crucially, the Buddhist conception does not divide the whole lifetime of the world into three ages. It only divides the lifespan of Buddhism itself—and, indeed, only Siddhartha Gautama’s dispensation of the recurring faith that is Buddhism—into three eras. And this dispensation is, in orthodox Buddhist though, only the thinnest sliver of the amount of historical time that has been or will be. The three eras of the dharma have nothing to say about cosmic history or the progression of time across the whole lifespan of the universe, as do the later sectarian Three Ages. Indeed, they are not even comprehensive and final within the context of Buddhism itself, as Maitreya will later restart the faith, which will presumably undergo the same three stages before the next buddha comes, meaning that instead of three stages of time, the three dharma periods are actually three stages of development that repeat endlessly throughout time, or at least those times when Buddhism is active. They thus describe a process of religious decay without any speculation on the larger temporal structure of the universe.

The Three Ages of the sectarians, on the other hand, are the temporal structure of the universe, not stages of a single teaching that appears within it. Furthermore, the three stages of the dharma are fundamentally pessimistic; as noted above, they describe a process of decay in which the truth of Buddhism is destined to be forgotten. The Three Ages scheme of the sectarians, by contrast, is inherently optimistic. The world is progressing toward a glorious final age of history, in which the earth will become a paradise, society will take on a utopian hue, and believers will enjoy the fruits of their belief. Just as importantly, the true teachings are not being forgotten. Rather, they are continually renewed throughout the Three Ages. The sectarian scheme is one in which the process of salvation is always bringing more people to enlightenment. The third age does not see the final failure of the salvation message but its greatest success. Even if there might be setbacks and terrors at the end of each age, the ultimate trajectory is a positive one. More and more people are reaching enlightenment and the work of salvation is coming ever closer to fruition. Given all this, it is clear that the Three Ages of the sectarians are completely different in nature, conception, and outlook from the three dharma stages of orthodox Buddhists. It is difficult to fathom, therefore, that they could have emerged as an elaboration of that earlier idea.

The same can be said for the sanyuan (三元—three primes) of Taoism, the idea that Daniel Overmyer, in Precious Volumes, seems to accept, however tentatively, as the source of the later sectarian Three Ages. Once again, however, such a conclusion is questionable. In Taoist thought, the three yuan are periods of world history which each end in a major series of disasters. Certain texts possibly indicate that they cover the whole existence of our universe, but others seem to suggest that, in fact, cycles of three yuan continually repeat throughout time. For instance, the Lingbao scriptures, the foundational texts of medieval Taoism, state that the lifespan of the universe contains innumerable time periods and temporal cycles. This makes it hard to tell whether the three yuan were actually the three periods of universal history or simply another process like that of the three dharma periods that cycles back around but never stops, leading to three basic stages but an endless number of ages. In the latter case, there would be far more than three yuan in the lifespan of the universe, just as there are ultimately far more than just three dharma periods.

What is more, there seem to be no positive connotations to the three yuan and no sense of progression. Their entire purpose is to bring about disasters upon the world. There is no optimistic hope for the future and no sense that things will get better in the next yuan, nor is there any further salvation or advance in enlightenment as one yuan turns to another. There is only the guarantee of catastrophe. In short, even if the three yuan in fact refer to three cosmic periods—and that still seems like a big if—as the later Three Ages do, they are completely different in character from the Three Ages. All the distinctive features of the Three Ages, particularly the sense of hope and progress, are completely missing from the sanyuan scheme. Rather, the sanyuan represent another pessimistic view of history, like the three stages of the dharma. It is very hard to see how the Three Ages with all their hope for the future, could have evolved out of this depressing vision of ever-recurring catastrophe, misfortune, and misery.

But as with the purity-fall-redemption narrative, the surest proof that the Three Ages belief of the sectarians did not originate from either the three dharma stages of the three yuan lies in the fact that the sectarians themselves insisted that the Three Ages were distinct from either of them. Like the purity-fall-redemption narrative, the baojuans contain plenty of references to the three stages of the dharma and the three yuan. But these are generally treated as different from the Three Ages of cosmic time. Instead, they are both largely invoked to describe the period of calamities that will mark the transition from the Second to the Third Age, not to the ages themselves. The Jiulian baojuan, for instance, announces, “As the years of the end Dharma approach, the world will be in disaster, and swords and spears will be wielded everywhere” but then proceeds to explain that “for all three buddhas, there is a time of decay and destruction, and there are disasters in each of the three apex periods” (qtd. in Overmyer 158), indicating that the period of the final dharma refers to the time of calamities at the end of each world-age, not to any one of the ages themselves.

Similarly, the Puming baojuan describes how “the Holy Patriarch Limitless” created the world when he “undertook the meaning of the three primes [= time periods], the one Buddha who divided into three teachings.” It is only after this primordial act of establishing the three cosmic ages that we are told of how the Patriarch “arranged Heaven and put the Earth in order, and established the chia-tzu [cycles] of the lower three primes” (qtd. in Overmyer 190). What Overmyer translates as the “lower three primes” are the three yuan, as in discussing the Longhua jing, he later renders a similar phrase as “the chia-tzu year of the lower yuan period” (at 253 and 264-265), with yuan left untranslated. Thus, the three yuan are established after the Three Ages have already been and thus, like the three dharma periods, they cannot be the Three Ages themselves.

Furthermore, the usage of the yuan periods is fundamentally linked to the times of disaster within the larger ages, as the dharma periods are—the Longhua jing specifically lists “the chia-tzu year of the lower yuan period” as the moment when the calamities begin—signifying that they are lesser timescales within the Three Ages and not synonymous with the ages themselves. Thus, there is no reason to think that the sectarians took either the three dharma periods or the three yuan as the basis on which to create the concept of the Three Ages when they were so adamant that the Three Ages themselves were completely distinct from these two earlier ideas.

Where, then, did the Three Ages concept come from? Throughout this series, I have highlighted the similarities between the Three Ages system of the later Chinese sectarians and that of Joachim of Fiore and his followers. I have, furthermore, proposed Joachim’s version as the source of the Chinese one. Joachim’s is the only pre-existing system that divides historical time—the lifespan of the universe—into three time periods and the only one to assign the three time periods to the most important figures of a religious faith. In Joachim’s case, this was the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit while in that of the sectarians it became the Buddhas Dipamkara, Gautama, and Maitreya. What is more, Joachim’s system proposes an optimistic and salvific view of time in which both humanity’s spiritual condition and its understanding of divine truths improve over time. This is precisely the understanding of time held by the sectarians. It was also a viewpoint completely absent from Chinese religion before them, and which thus could not be rooted in earlier Chinese developments. Indeed, both Joachim and the Chinese sectarians had to find new terminology to refer to the ages because none of the traditional words for time in either of their languages fit the new conception. Thus, Joachim called the ages Status and the sectarians referred to them as Yang, both applying a new sense to an old word because there was no other adequate means of expressing the extraordinary new idea in the language available to them.

Both Joachim and the sectarians have a conception of recurrent and progressive revelation that was unprecedented in their respective cultures. For both, this meant not only that history was seen as an ongoing process of increasing spiritual illumination but also that new insights and new ways of understanding old ones would become manifest as the Third Age drew near. Both Joachim and the sectarians expected the coming of a new, more egalitarian social order and both experimented with new forms of social organization. They shared a worldview that emphasized patterns and repetitions in history and each of them expected that a series of calamities would punctuate the end of each age and the beginning of the next. And of course, both Joachim and the Chinese sectarians regarded the Third Age as near at hand and proclaimed it to be a glorious utopian era of peace, harmony, and unprecedented spiritual development. At the same time, they saw it as not an entirely new transformation but as the result of processes already at work within history itself. Furthermore, both Joachim and the Chinese sectarians recognized that the Third Age would be within time; the end goal of faith for all of them was not to live in that time, however wonderful it may be, but to attain citizenship in Heaven and in the world to come after this universe has ceased to be.

Additionally, those developments in Chinese sectarianism that would have been too daring for Joachim still find parallels in the teachings and actions of his most radical followers. The tendency of the sectarians to produce baojuans that they heralded as the “true scripture of the future” (qtd. in Overmyer 161) is reminiscent of Gerard of Borgio San Donnino, who announced that the Bible would be replaced by a new “eternal gospel” for the Third Age. The high position which women were accorded in the Chinese sects, serving as chapter heads, sect leaders, and sometimes even as manifestations of God, is much akin to the elevation of women seen amongst the Guglielmites, who proclaimed their female founder God in the Person of the Holy Spirit and declared another woman pope. Indeed, the radical egalitarianism and suspicion of the official religious hierarchy found among the Chinese sectarians may have been too much for Joachim, who still hoped for a great reforming pope, but they were certainly of a piece with the interpretation of his ideas advanced by groups such as the Spiritual Franciscans and the Apostolic Brethren. Even the Longhua jing’s curious addition of a fourth age to the original three had already been preempted by Fra Dolcino, the leader of the Apostolic Brethren, who saw fit to add a Fourth Status onto Joachim’s original three.

Even one of the more unique features of the sectarian Three Ages concept, the assigning of the colors green, red, and white to the First, Second, and Third Age, respectively, has something of a precedent within Joachimism. In the Christianity of Joachim’s time, white, green, and red were the colors assigned to the three theological virtues of faith, hope, and charity. That they acquired an eschatological significance as Joachimism was gaining a foothold is testified to by Dante’s Divine Comedy. It is too rarely acknowledged how resolutely apocalyptic of a work the Comedy is; the text has a decidedly Joachimist flavor and continually evokes the prophetic figure of the Last World Emperor. One of the work’s most highly charged apocalyptic moments occurs in the last cantos of the Purgatorio, when Dante finally encounters Beatrice in the Garden of Eden atop Mount Purgatory.

This section begins with a precession of symbolic figures from the Book of Revelation and ends with Dante’s most famous Last Emperor prophecy, the one that associates the Last Emperor with the number 515 as a holy counterpoint to the Antichrist’s number of 666 (or 616). It is a scene rich in eschatological detail, a full analysis of which is beyond the scope of this article. What is worth nothing here, however, is the important role the colors of green, red, and white play in this tableau. The precession of apocalyptic figures culminates in the arrival of the Merkavah—God’s chariot from Ezekiel 1. After the Merkavah arrives,

Three ladies came dancing in a circle

By the right wheel; and one of them was so red

That she hardly would have been visible in a fire;

The next was as if her flesh and bones

Had been entirely made of emerald;

The third appeared to be of new-fallen snow;

And now they seemed to be guided by the white,

Now by the red; from the way that one sang

The others took the time, whether slow or quick.

(Purgatorio XXIX.121-29).

These three ladies are allegorical personifications of the theological virtues, faith, hope, and charity. But more important for our purposes than their exact symbolism is the fact that these three colors appear just as the apocalyptic tableau reaches its first climax with the arrival of the Merkavah and the subsequent appearance of Beatrice on the holy chariot. Beatrice herself is dressed in these same colors: green, red, and white. The poem describes her outfit in the next canto: “Over a white veil, crowned with olive, / A lady came to me, under her green cloak / Clothed in the color of flame” (Purgatorio XXX.31-33). Thus, this apocalyptic scene emphasizes these three particular colors repeatedly at its central moment, the reunion of Beatrice and Dante, going so far as to dress Beatrice herself in them. This suggests that the colors themselves carry great apocalyptic significance.

Given Dante’s own debt to previous apocalyptic and Joachimist thought, we can conclude that he did not invent the eschatological importance of these colors. Indeed, they seem to have had a much wider significance than him. They already must have acquired their apocalyptic symbolism in the prophetic atmosphere of thirteenth- and fourteenth-century Italy. They certainly seem to have enjoyed a wide currency throughout Europe. Indeed, evidence of this can be found in a rather unexpected place. About a hundred years after the Divine Comedy was written, the controversial English mystic Margery Kempe decided to have her own prophetic experiences put to paper for the benefit of posterity. The Book of Margery Kempe duly recounts the many visions of and dialogues which Christ, the Virgin Mary, and other key figures of the faith that Kempe had over the years. In one such vision, Kempe sees the Holy Trinity seated on cushions, which prompts Christ to explain the scene:

And you think that my Father sits on a cushion of gold, for him is appropriated might and power. And you think that I, the Second Person, your love and your joy, sit on the red cushion of velvet … Thus you think, daughter, in your soul, that I am worthy to sit on a red cushion in remembrance of the red blood that I shed for you. Moreover, you think that the Holy Ghost sits on a white cushion, for you think that he is full of love and cleanness, and therefore it beseems him to sit on a white cushion, for he is the give of all holy thoughts and chastity. (Kempe I.86, pp. 153-54)

In this vision. we find a similar color scheme to Dante’s but expressed in a manner more in line with what we see in China. Just as the Chinese sectarians did, Kempe associates the three colors with the three Persons of the Trinity. What is more, she assigns the same colors to the Christian Trinity that the sectarians assigned to their Chinese equivalents. Thus, the Second Person of the Trinity, the Son, is associated with the color red and the Third Person, the Holy Spirit, with the color white. Even the fact that the First Person, the Father, is here allotted the color gold instead of green only enhances the likeness, since the Chinese sectarians often made a similar substitution by assigning the color yellow instead of green to the first member of their divine triad and his associated epoch. Thus, Margery Kempe has managed to allocate these three colors to the Persons of the Godhead in the exact same manner as the Chinese sectarians often did.

Either it is an extraordinary coincidence or there is a deeper connection here. The Book of Margery Kempe is, admittedly, not a Joachimist work. Unlike the Divine Comedy, it neither gestures toward Joachim’s scheme of history nor does it share any of his preoccupations. Indeed, Kempe is at pains to paint herself as completely orthodox, despite her extraordinary claim to be in constant dialogue with Christ. And yet, throughout her life, she was dogged by claims of having been influenced by the Lollards, and the Lollards certainly owed a debt to Joachim. Given the potential Lollard connection, then, it is not difficult to imagine the color scheme employed by Kempe also had a place in Joachimite circles, where the association of the three colors with the three persons of the Trinity would also naturally have extended to the Three Ages themselves. Thus, in at least some branches of Joachimism, there would have been an assignment of either green or yellow to the First Age, red to the Second, and white to the utopian Third Age, which is exactly what we see happening among the sectarians in China.

Could the sectarians, then, have adopted the three-color scheme for the Three Ages from the Joachimites? After all, the significance of these colors in particular to them and their near-universal agreement as to how the colors should be assigned has never been adequately explained. The fact that white was Maitreya’s color can certainly be cited to explain why it was always applied to the Third Age. But what about the other two time periods? Why were green and yellow routinely chosen for the first and red regularly assigned to the second? Perhaps the answer is that Joachimism was indeed imported to China around the time Dante was writing his Comedy, bringing with it the unique and distinctive green-red-white color scheme that quickly became one of the defining features of Chinese apocalyptic thought.

We can apply this solution more broadly. If Joachim’s teachings arrived in China in the thirteenth or fourteenth century and were assimilated into the local apocalyptic narrative, it could explain why elements so eerily reminiscent of Joachimism begin to appear regularly in Chinese eschatological texts starting with the Huangji jieguo baojuan soon afterward. This penetration of Joachimism into Chinese popular apocalypticism could explain some of the features of later Chinese sectarianism that peculiarly echo Christianity, such as the importance placed on a single creator deity and the trinitarian conception of that deity. Perhaps even the unique tendency of the sectarians to imagine that deity as female could derive from a misinterpretation of the Catholic veneration of the Virgin Mary—liberally mixed with preexisting ideas about the Queen Mother of the West, of course. Some of the ideas seen in the baojuans and Chinese sects might be direct borrowings, some might be the result of parallel evolution from a shared Joachimist basis, but all would derive from Joachim in one way or another. This not only solves the problem of where the Three Ages conception came from but also reveals a new source for the sectarians’ most distinctive beliefs and practices.

That there is nothing overtly Christian about the beliefs of the later sectarians, no mention of Jesus, Moses, or St. Paul in their mythological narratives, hardly counts against this theory. As I have amply demonstrated in previous entries, Chinese apocalypticism tended to borrow from all the belief systems it encountered but relied chiefly on the symbols of whichever religion was most popular amongst the common people at the time. And it would take many centuries before Christianity could begin to make that claim. Thus, to take in Joachimist ideas but swap out their Christian symbols for Buddhist ones, to replace the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit with the Buddhas Dipamkara, Gautama, and Maitreya, was perfectly in keeping with the syncretic nature of Chinese apocalyptic sectarianism. After all, they continued to use the Primordial Buddha as an alternative designation for the Unborn Mother for hundreds of years, even as the two conceptions of the supreme deity grew increasingly divergent. By the same token, the fact that the sectarian system contained a plethora of Buddhist, Taoist, and esoteric elements does not invalidate the possibility of Joachimite influence. We have seen how any good or popular idea, whether it came from this religion or that or even from popular culture, made its way into the beliefs of the sectarians eventually. Inevitably, they combined with symbols and concepts from other sources, even if those divergent ideas or symbols would never have fit together in their original forms. There is no reason to think, then, that Joachimism would have been treated any differently by the sectarians.

The only major divergence between Chinese Three Ages thought and the ideas of Western Joachimism lies in their quite different treatment of the monastic life. For Joachim, monasticism was the ideal form of social order and would serve as the model for the utopian society of the Third Age. He expected the Church to be reformed on monastic lines and placed the monastery at the center of the communal structure in the Third Age, with a new kind of monastic structure that would accord with the governing principles of the coming time. He expected his new “spiritual men,” who were going to shepherd the world into this glorious future, to be members of the new holy orders that he foresaw. Many of Joachim’s most devoted, most influential, and at times most radical followers came from a monastic background and held monasticism in just as high regard. Thus, the Spiritual Franciscans cited Joachim in their struggle to return the Franciscan Order to St. Francis’s original vision and Peter John Olivi, himself a Franciscan, claimed Francis’s founding of a new form of monastic life heralded the coming of the Third Age. Monasticism was, in many respects, the lifeblood of the Joachimite movement, taking a leading role in both the lives of Joachimites themselves and in their apocalyptic visions.

By contrast, the Chinese sectarians displayed a deep suspicion, and often an outright hostility, to the Buddhist and Taoist forms of monasticism that existed in their own day. We have seen already how the Huangtian jiao expressed skepticism of monastic life and championed the lay community as the locus of salvation. Their viewpoint was relatively mild. Other sectarians were harsher. The eighteenth-century Foshuo Dudou litian hou hui shouyuan baojuan (佛説都斗立天後會收圓寶卷—Precious Scroll of the Buddha’s Teaching Regarding the Dudou Palace, Establishing Heaven, the Final Assembly, and Attaining Completion) contains this diatribe against both monks and priests:

What Taoist priest ever gave birth to a Taoist priest? What old monk has given birth to a young monk? The patriarchs of all the myriad teachings have all been produced in lay households. Without filial piety to one’s parents, all is in vain. The Ancient Buddha is not among monks or priests; he fell [to Earth] in a lay household. (qtd. in Overmyer 275)

This clearly establishes the superiority of the lay life, the life of worldly responsibility and the family, over the religious ritual of priests and the renunciation of monks. It is in keeping with the hostility of many of the baojuans toward the monastic orders. A common sectarian theme is that it is not the monks, with their secluded way of life and their restrictive rules, who form the elect of the new age, but ordinary people. This is quite the opposite of the reverence for monasticism that we see in Joachimism.

But this is not as much of a contradiction as it first appears. The contrasting portrayals of monasticism stem, I believe, from the different positions monks and monasteries occupied in the social hierarchies of Western and Chinese society. In the West, monks were a part of the Church hierarchy, but they formed the lowest rung. They were above the laity but subordinate to ordained priests. Some orders, such as the Cistercians that Joachim seceded from, were swiftly acquiring sway and influence, but they had yet to reach the heights of power that monastic orders would enjoy in the coming centuries. Oftentimes they seemed quite powerless, subject to the capricious whims of priests, prelates, and popes. One only has to look at the early history of the Franciscan Order to see plentiful evidence of this, from St. Francis’s difficulties in getting the order recognized to the subsequent destruction of his original vision for it and the ultimately futile efforts of the Spiritual Franciscans to maintain his standards in the face of papal opposition. Monasteries also practiced poverty and simple living more fully than did the priesthood—even if the wider orders were just as susceptible to the sin of avarice as the priests—and functioned on a more egalitarian basis than the Church at large. It thus made sense for the Joachimites to project their hopes for a better future onto monasticism, especially once St. Francis appeared and preached a new form of monastic life based on absolute poverty and communal service. For them, an adherence to monasticism was a commitment to fostering the greater levels of equality, community, and simple living that they hoped to see in the age to come.

In China, on the other hand, Buddhist monks made up the highest levels of their religion’s infrastructure. They not only lived a monastic life of isolation but also carried out the priestly functions of the faith and performed its rituals. What is more, Buddhist monasteries were directly governed by the state. Unlike in the West, where joining a monastery was a relatively open process, imperial authorities in China tightly controlled who was admitted into Buddhist monasteries and established quotas on the number of people who could become monks each year. Therefore, monasticism in China was deeply intertwined with the highest levels of power. It thus makes sense that whereas the Joachimites railed against priests and the contemporary papacy for lusting over wealth, land, and power, the Chinese sectarians took the monks to task for the same abuses. Both were cases of a less powerful and marginalized religious community taking aim at the venality and corruption rampant in the highest levels of the official religious hierarchy. In both cases, the goal was a more egalitarian social order built upon the existing forms of social organization that seemed best for the purpose. Indeed, when Western monasticism lost its idealistic sheen in the centuries after the Church abandoned St. Francis’s principles, latter-day Joachimites—particularly those aligned with the new Protestant Reformation—attacked monks with a vigor and vehemence that would have done the Chinese sectarians proud.

It should also be noted that, in their criticism of monks, the Chinese sectarians did not so much depart from Joachim’s view of future spiritual development as rearrange it. Joachim had made the Three Ages correspond with three particular ways of life. He describes them in the Liber Concordie thusly:

Thus because the transformations of times and works themselves attest that there are Three Status of the world—it is permitted for all this present time to be called one age—therefore there are three orders of the elect, though it must be acknowledged that the people of God are one, one populace as we understand both from the authority of the holy fathers and also manifestly from the evidence of things itself. And indeed, the first of these orders is that of the married, the second is that of the priests, and the third that of the monks. (Lib. Con. 2.1.5)

The First Status corresponds to the married way of life, to families and the laity. During the First Age, the life of the family was preeminent; married men and heads of families controlled both religious life and society as a whole. The Second Status corresponds to the priesthood. During the Second Age, the priesthood took over the leadership of religion and society building the Catholic Church, which in turn upheld celibacy as more perfect than marriage. The Third Status will correspond to the monastic life. During the Third Age, monasticism will be the ideal form of life and monks will be in charge of both religion and society at large. There is therefore a progression in the ways of living from one era to the next. In each age, the form of life most appropriate to the time is dominant both spiritually and socially. But as a new age comes, another, more spiritually developed form of life becomes dominant instead. The previous forms of life do not fade away—Joachim fully recognized that people would continue to marry and have children and priests would still exist in the Third Age—but in each age they give their place of preeminence to a spiritually superior form of life that guides society to greater perfection. This understanding of the three ways of life is a key component of Joachim’s Three Ages and, as we saw previously with Fra Dolcino, was one that remained central to his followers’ own understanding of the unfolding of history.

The interesting thing is that the baojuans also have this same sequence, with one crucial difference. The order of the ways of life is reversed. The Longhua jing proclaims, “The Lord Lao … saved all the immortals. … Śākyamuni saved the monks and nuns … and the Sage saved lay households” (qtd. in Overmyer 268). The “Sage” in this passage is Confucius. Overmyer’s selection of text makes the idea seem a little confused, but a passage from the Dudou litian baojuan (the text cited above), provides more clarity on this idea:

[After the Lord Lao and the Ancient Buddha, the teaching] was transmitted to Confucians living in lay households. The first two assemblies were of monks and priests. They lived in cloisters and sat in mountain forests. From everywhere they received food and offerings. However, they did not complete the task but fell into saṃsāra. In the period of the third yang, the principles of Confucius and Mencius put the world in order. Through the three bonds and five constant virtues, [the people] are transformed into worthies. (qtd. in Overmyer 275)

What we have here is a sequence where three ways of life correspond to the Three Ages of sectarian thought, which the Dudou litian baojuan refers to as “assemblies,” a common designation for them ever since the Huangji jieguo baojuan. The first two ages are those of the monks and priests. But the way of life established by Confucius, as the Dudou litian baojuan specifically states, belongs to the “third yang”—the Third Age—and we know from the Longhua jing that this is the life of “lay households.” We need not be troubled by the fact that both texts credit these three ways of life to the founders of the three major Chinese religions, who could not all have lived in different ages and who—except in the Longhua jing’s peculiar case—could not have lived in the third. Joachim similarly credited all three ways of life to Old Testament figures, who all lived in the First Age according to his reckoning, without it damaging his basic argument that each way of life became dominant in a different age. What is important to note is that there is the same association of the ages with particular modes of life that we see in Joachim and there is also the same progression from less to more spiritual ways of life. Even more strikingly, the three modes of life themselves are the exact same ones as in Joachim: married, priestly, and monastic.

But the baojuans reverse the order in which the modes of life evolve. Joachim had the married life—the life of the laity and the household—then the priestly life and finally the monastic life. The Dudou litian baojuan has the monastic life, then the priestly life, and finally the married life of the laity, with another dig at monks and priests thrown in. The order has been changed from Joachim’s version but not in a haphazard manner. Rather, it is turned exactly on its head. This suggests a deliberate departure, an attempt to maintain the basic form of the earlier model while altering the direction of its evolution. This had a definite purpose, which was to support the baojuans’ criticism of monks and idealization of lay life. Thus, it seems that not only Joachim’s Three Ages but the concept of three ways of life associated with them must have been passed to these later baojuans relatively intact. Even the baojuans’ greatest departure from Joachim, then, manages to reveal clear traces of his incredible influence.

But for all the above points to hold up, there must have been a means by which Joachim’s system of the Three Ages could have arrived in China in the years preceding the writing of the Huangji jieguo baojuan and the beginnings of Three-Ages sectarianism. In a previous entry, I demonstrated that such a means did exist. There was a Franciscan missionary effort in the last years of the Yuan led by one John of Montecorvino. He founded two churches in Beijing, one in 1299 and the other in 1305. This was around the time when the Spirituals were feuding with the Convectuals for control of the order to which John belonged. It was also exactly in these years that Dante was penning his Divine Comedy. Given how popular Joachimism was in Europe at the time and in the Franciscan order in particular, it is hard to imagine that someone in John’s missionary train, or any of the new arrivals to follow him, did not harbor Joachimite ideas of their own. John’s mission comes from the right place, began at the right time, and has all the right connections to have imported exactly the form of Joachimism that we see reflected in the beliefs of the Chinese Three Ages sects.

The Franciscan mission John founded was located in Beijing, the city where the Huangji jieguo baojuan would later be written. We have already seen how the wider Zhili region in which the missionaries preached—along with its surrounding provinces—would give rise to countless Three Ages sects. Thus, the mission was in the right place to shape the beliefs of the future sects. It was also there at the right time. The Franciscan presence was a long and sustained one, lasting until after the Ming Dynasty’s founding in 1368. It is only sixty-two years from that date to the year of the Huangji jieguo baojuan’s composition, 1430. In a country where apocalyptic ideas linger on for millennia, six decades is not too long a time for Joachim’s teachings to remain in popular memory. Indeed, since the Huangji baojuan expresses beliefs that had already reached a mature form, the Three Ages system of the sectarians was probably formulated in less time than the sixty years between the Franciscan expulsion and its publication. It is very possible that the first Chinese version of the Three Ages concept was created while the Franciscans were still there, among the very population to whom they were preaching Christ’s word, seasoned perhaps with a healthy dash of Joachim’s own words and ideas.

While this is the only route I know of by which Joachimism could have been transmitted to China in time to leave a mark on the early Ming sects, another avenue of influence opens up in the late Ming and Qing Dynasties. The Huangji jieguo baojuan and the early sects would have had to rely on what remained of the departed Franciscans’ Joachimist teachings. But later texts such as the Longhua jing and the Dudou litian jing did not have to depend upon folk memories of missionary effort now centuries in the past. They could get their Joachimist ideas directly from the source, as it were, because a new crop of Catholic missionaries had arrived in China. The remarkable fidelity to Joachim’s ideas seen in these later baojuans, such as the progression of the three ways of life detailed above, is probably due in part to the Chinese sects encountering those ideas afresh as the missionary orders returned to their shores. The Catholic Church was back in China and its own subsequent interactions with the Three-Ages sectarians provide even further evidence of a pervasive Joachimite influence on Chinese sectarianism.

Works Cited

Alighieri, Dante. The Divine Comedy, translated by C. H. Sisson. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008.

Joachim of Fiore. Liber de Concordia Novi ac Veteris Testamenti, edited by E. Randolph Daniel. Transactions of the American Philosophical Society, vol. 73, no. 8 (1983): pp. 1-455. All translations mine.

Kempe, Margery. The Book of Margery Kempe, translated and edited by Lynn Staley. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2001. I have used this modernized version to make reading easier, but the original Middle English text can be accessed as part of the University of Rochester’s Middle English Text Series.

Overmyer, Daniel L. Precious Volumes: An Introduction to Chinese Sectarian Scriptures from the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1999. All bracketed text is original to Overmyer.

Seiwert, Hubert. Popular Religious Movements and Heterodox Sects in Chinese History. Leiden: Brill, 2003.