This column is not about gun regulations. Rather, I am offering cultural observations about two elements that are missing from the current debate, both of which are antithetical to spiritual wellbeing and may contribute to gun violence in subtle ways.

I am referring to (1) the casual threat of deadly force that seems to have become synonymous with parts of American culture and (2) toxic/hyper-masculinity, which represents a spiritual wound that needs to be healed.

Both are relevant to the gun debate—each in its own way.

Now, before you read the rest of my column, I want you to know that I love living in America. I became a US citizen in 2013 and am committed to raising my family here, to being a part of the community. I am engaging in this debate because I care.

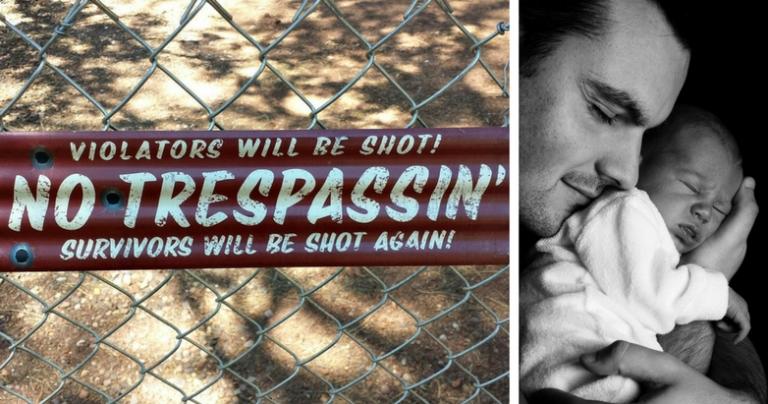

The Casual Threat of Deadly Force

As I have written about before, gun ownership is very high in my home country of Iceland. About 60% of the population owns guns. Granted, these are mostly shotguns and rifles—as handguns and semi-automatic weapons are off limits to the public—but, nevertheless, there are a lot of guns in Iceland. However, people generally don’t use their gun ownership to casually threaten other people.

That’s a stark difference between Iceland and parts of American culture. Here, many people casually threaten deadly force, sometimes without even thinking about it.

For example, in my neighborhood, there were a few burglaries last year. In response, several people printed stickers that read “protected by the 2nd Amendment” and placed them in their windows.

If we take a moment to think about the implications, people are saying that burglary is punishable by death. I doubt that any courtroom in America would agree with that sentence. It would be considered disproportionately harsh. And yet, the culture has become such that it is considered okay to shoot to kill in response to minor infractions of personal privacy.

To some, this may seem innocuous. They will even claim that the threat of such a harsh penalty generally discourages crime, but my point is that from a spiritual perspective—and this is in line with the teachings of most of the world’s religions—a threat of violence should be a last resort, not a first response.

If we raise our children to believe that deadly force is something that we should casually threaten, I think that represents a much bigger spiritual failure than allowing them to watch violence on TV, for example. I think we should instill in them a deep respect for human life. Reaching for a gun should be their last option, not their first instinct.

Toxic/Hyper-Masculinity

Most mass shooters are men. In fact, most violent crimes are committed by men. It’s a hard fact. In the extreme, testosterone has two instincts; to have sex with it or kill it. Fortunately, testosterone isn’t the only hormone coursing through men’s bodies as they also produce oxytocin (the caring hormone). Through socialization, men can be taught and trained to harness the positive aspects of their masculinity and reduce the potential harm they can cause.

This kind of training usually comes from caring men—the kinds of men that can show a balance between firmness and compassion.

The problem is that a lot of little boys and young men are never exposed to caring men.

Let me give you an example.

In the nineties, I worked at a daycare center for nine months. During that time, I was lucky enough to be invited to a conference about men in the education system. The speaker, whose name I have unfortunately forgotten, pointed out that boys with single mothers could go through the school system, from the time they entered daycare until they entered either middle school or high school, without ever being exposed to men.

“What kind of effect does that have on the boys?” he asked.

His initial assumption had been that boys surrounded by women every day would become feminine, but then he showed us data that pointed in the opposite direction. Boys without caring male role models either looked to hyper-masculine stereotypes in movies, comic books, and video games, or, saw how women behaved, and tried to be the exact opposite of that.

This can also be true of boys who’ve had absent fathers, as numerous writings about the so-called “father wound” have demonstrated.

Recently, I have been reading about men in prison and the people who work with them. Most of the men come from abusive or broken families—either single mothers or no parents—and have never been exposed to a caring male role model. That doesn’t excuse their crimes, but it does provide a compassionate viewpoint that is worth considering.

Parts of a Larger Puzzle

If boys were exposed to more caring men and people stopped threatening deadly force so casually, that wouldn’t be enough to stop gun violence in this country. However, I believe that these are important pieces, parts of a much larger puzzle, that need to be addressed in some way, in addition to addressing things like mental health, restricted access to assault weapons, and general security for our children.

There are many people adding their voices to the gun debate these days. All I wanted to do was offer a spiritual perspective about two elements that are not being discussed. If this column has empowered one man to become more caring, encouraged him to be a role model for both his sons and other boys around him, or, has gotten one person to rethink how the casual threat of deadly force affects the children in his or her vicinity, then it was worth writing.

Gudjon Bergmann

Interfaith Minister, Author, and Speaker

Founder of Harmony Interfaith Initiative

Follow me on Facebook and Twitter

Pictures: Pixabay.com CC0 License