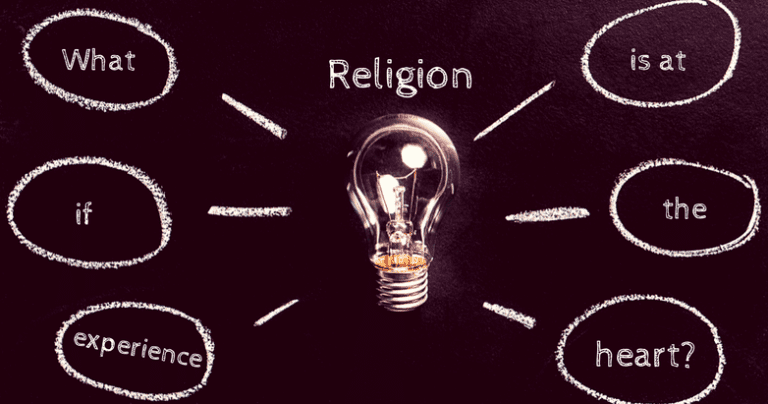

During my studies to become an Interfaith Minister, I kept thinking:

What if we could better understand each other?

What if people, who practice different religions or tread different spiritual paths, could find more common ground?

Those are powerful questions.

And I found some answers.

Choosing Between Two Different Types of Faith

In my search, I started by examining two distinct types of faith.

One is narrative in nature. It focuses on who said what, where, what that means, and so on.

The other is experiential in nature. It focuses on spiritual experiences that can be revealed through a variety of religious practices.

In narrative or storyfaith interactions, we learn about each other’s stories, myths, and cultures, but because of the inherent differences, there will always remain roadblocks on the route to greater understanding.

That is why I put storyfaith aside in my search for common ground.

Not because there is anything inherently wrong with the narrative path, but rather because I saw its limitations in creating greater interfaith understanding.

That left me with experifaith.

Two Paths of Experifaith

As I studied the major religions of the world in search of experiential elements, I saw two things. Firstly, there is tremendous variety when it comes to spiritual and religious practices. Secondly, experiential practices can (mostly) be categorized into one of two paths, the paths of oneness and goodness.

Those who tread the path of oneness seek peace of mind and nondual unity. Oneness seekers yearn to taste the quintessence of their being, transcend time and space, and be unified with the one.

While this yearning can be found in the mystical traditions of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, it is more prevalent in Eastern religions and wisdom traditions.

Those who tread the path of goodness, on the other hand, traditionally see stark choices in the world. They believe we should choose love, compassion, beauty, truth, and altruism over hatred, fear, anger, judgment, and other opposites of goodness.

Again, while this path is also prevalent in many Eastern traditions, being good (definitions of which differ subjectively, although there are some universals) has been the flagship of the Abrahamic religions in the West.

How Are the Two Paths Different and What Does that Mean?

On the face of it, these two paths could not be much more different—one is external and the other internal—and yet, the more I researched, I realized that both paths have survived side-by-side in all of the world’s religions as far back as I could see.

Side-by-side is the operative concept.

Here is how I explain the difference in my book:

“Co-existence, however, does not mean that the two paths are the same. Over the centuries there have been numerous attempts to merge the two, for example, by saying that there is only oneness and that oneness is good. These attempts have all failed because they have run into the same theological dilemma. Oneness is nondual in nature, as in, there is only one, while goodness is dual in nature because for it to exist there must be something other than good.

If oneness is the coin, goodness is one side of the coin; if oneness is the ocean, goodness is a set of benign waves; if oneness is the entire color spectrum, goodness is represented by bright and beautiful colors. It is impossible to reduce the coin to one side, the ocean to a set of waves, or the color spectrum to only bright and beautiful colors. Oneness is all that is. Goodness is a choice between two or more things; between yin and yang, heaven and hell, high and low, good and bad… the list is never-ending.

Attempts to unify or merge the two are forever fraught with this philosophical inconsistency. How can oneness be everything when it can be reduced to less than that? It is much more consistent to see the two paths as connected but separate.”

My conclusion was simple. Even though adherents of the two may disagree from time to time (or all the time), both of these paths are equally valid. We must respect them as such, allow them to exist side-by-side, and not try to either claim that one is better than the other or claim that they are the same.

How Does This Help Us Understand Each Other?

Because these paths are experiential, it means that if people are not on a path or if they tinker with experiential practices from time to time, they are about as likely to understand each other as a deep sea turtle and a soaring eagle—who, for obvious physical limitations, can never see each other’s point of view.

However, when people sincerely practice their religion or spiritual path—and in the model, I identify four major groups of religious practices, including (i) experimentation (from meditation and prayer to sweat lodges and trance dancing), (ii) contemplation (including reading of scriptures, private thought, and philosophical discussion), (iii) love (caring enough to increase the personal capacity to empathize), and (iiii) service (actively helping others)—and share their experiences, there can be a melding of minds.

Sufis, Hindus, and Catholics who meditate can, for example, come together and share their experiences with meditation, rather than focus on theology.

Christians, Muslims, and Buddhists, who live a service-oriented life, can come together and do good (as many interfaith organizations do). Through serving humanity side-by-side they feel a deeper appreciation of each other, despite differing theologies.

Reality and Hope

As I studied narrative theology and human inclinations, I came to agree with social scientists who claim that humans are tribal in nature. There is no escaping that. As the old Arab Bedouin saying goes it is:

“I, against my brothers. I and my brothers against my cousins. I and my brothers and my cousins against the world.”

For that reason alone, a unity of theology or religion will never exist.

The bright side of the equation, however, is that a unity of experience is possible. Even though theologies differ, we humans are much the same. We have the same tools—body, mind, and spirit—to experience our chosen/inherited religion or spiritual path. And when we compare the outcomes, when we focus intently on our personal experiences instead of parroting theology, when we share how certain practices make us feel and how they help us to become better people, we are apt to see that we have more in common than we realize.

That gives me hope and is why I think that the Experifaith model has the potential to build bridges.

Gudjon Bergmann

Author & Interfaith Minister

Visit www.experifaith.org to learn more.

Picture: Pexels.com CC0 License