Sacrifice was the locus of the sacred in the ancient world and still is in many parts of the world today. It is high time to restore these ancient and venerable rites to contemporary Pagan practice.

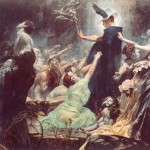

In the ancient world, like unto elsewhere today, the rite of animal sacrifice was central to the experience of the Gods. We can remember the way of sacrifice by using a sketch of Walter Burkert’s reconstruction of the Greek rite. It was a three-phase process following on sundry ablutions and preparations. The participants would process to the altar; purify the space, people, and offerings with water; likewise fumigate them with incense; and inscribe a circle on the ground with the participants inside. Then, the rite proper would begin. Preliminary offerings would be poured out and prayers made, addressing the offerings to the Spirits and Deities intended. Then, further and probably more elaborate and formal invocations were performed, and the animal dedicated would be swiftly slaughtered. The animal theretofore had been especially well treated and kept calm and was by this considered ‘willing’ to be sacrificed. The animal was immediately butchered and the traditionally prescribed portions placed in the fire on the altar while the rest was cooked or distributed. After this, a third phase of concluding offerings and prayers are made.

Think about this a moment: How different is this from an ordinary Sunday church barbecue with exceptionally fresh meat? The victim was killed in a respectful, even holy manner, a far cry from today’s factory farms. Certainly, no one who eats meat today can have an ethical objection to this practice. Any of the mechanical considerations of hygiene are simply a matter of skill, lost today in our culture, but restorable by careful consideration or learning from those cultures that still perform this venerable rite.

Some in their ignorance of the ancient world and how offerings are generally done even today associate sacrifice with privation and pain, a God killing His Only Son in expiation, for example. While it is perhaps noble to make offering with your last or most precious bit, sacrifice is not based on suffering. Most sacrifice is done in a mood of thanksgiving and comes from the abundance of the offerer. In the ancient world, after the offering, the rest of the animal generally was cooked and eaten in a mood of celebration. (Dancing was another suppressed dimension of ancient Mediterranean religion: few public rituals did not include it. I’m guessing that is it was what you did while dinner was cooking.)

The purpose of sacrifice is to build, maintain, and correct our connection with the Gods, which is why it had to be stopped in ancient times. It is essential for theistic Pagans, but I know atheist Pagans who join in the practice. The common explanation of sacrifice is to somehow ‘feed’ the Gods, but this is generally challenged by the more philosophical understandings of ancient religion that evolved over time. In the West, this view is championed by Iamblichus of Chalsis and found in the book we now call De Mysteriis, arguably the cornerstone text of the western magical tradition. Iamblichus points out that the Gods and all the entities down the hierarchy of being are above humans on the ontological scale and so cannot be affected, never mind fed, by such as we. Rather, sacrifice properly done affects the sacrificer by attuning us to the Gods we invoke (never mind bonding us to those we share it with). A careful analysis of Iamblichus’ writing discloses that the act of offering physical substances to the Greater Ones is best understood as a kind of material invocation.

Material offerings themselves are part of a continuum of offerings stretching from the material to the purely noetic or ‘mental,’ with a kind of hybrid between them made of both ‘matter’ and ‘thought’. Speech is an example of this, which is both material (being sound, experienced through the senses) and mental (having meaning, experienced and understood by the mind). This middling sacrifice, between the material and the mental, can be termed ‘symbolic.’ The attentive practitioner will immediately recognize that symbolic offerings composed of words are otherwise called ‘invocations.’

In his Of the Abstention from Animal Food, Porphyry argued against animal and all material sacrifice. He is often cited by Christians for this, which is ironic since he was one of their greatest opponents. (They destroyed his massive work, “Against the Christians,” such a loss . . .) Iamblichus objected to Porphyry’s thesis by noting that most folks can’t do the purely mental offerings Porphyry enjoined, and that material offerings are required for material benefits from the sacrifice. In Iamblichus’ formulation, it seems that the benefit derived from a sacrifice comes through with the same degree of materiality as the offering. Mental offerings produce mental benefits and physical offerings produce physical benefits.

In a discussion at Pantheacon on sacrifice a number of years ago, an Iranian Zoroastrian was present who said, “If blood does not flow, it is not sacrifice.” But in the ancient world, as in some Hindu traditions and elsewhere today, there emerged the ideal of blood-less offering. Pythagorus in some accounts counseled thus, and there were certain temples and altars at which blood-sacrifice was forbidden. In fact, there was a large array of material sacrifices that did not involve killing animals. Besides the aforementioned libations (primarily watered wine, but also plain wine, oil, milk, and even water), flowers, fruit, vegetables, and grain, especially barley, were offered. Specially made cakes were also quite common, and, of course, the ever-present incense.

The ancient Greeks also made gifts of craft and art to the Gods, dedicating them as a mode of sacrifice. These were then added to the treasury of the God rather than being destroyed. Statues were also made, sometimes commissioned, and after being duly sacrificed, became objects of worship. Copying out sacred writings is also a kind of offering, very literally spreading the word. These are often collected and stored in Icons, or sacred statues, as part of the Icon’s sanctification. Coin, which Pagans know to be one of the four great elemental magical tools, was also offered and used to support the shrine. When done properly, donations, tithes, and bequests all become sacrifices that redound to the offerer with the spiritual benefit of the Deity.

There are other methods such as those in Tibetan Buddhism that Pagans can adopt, such as making offerings with mantra and symbolic gesture, or sets of offerings based on the four (or five) elements and the senses to create a kind of completeness. Also, water can be poured out into receptacles and magically transformed into the proper offerings. Ghi(clarified butter) can be likewise transformed and poured into fire with great dramatic effect. Mandalas, graphical representations of the world or parts of it, made of gems and minerals, herbs and grain, or just colored sand can be made and destroyed as offerings.

Some traditions develop the idea of merit, a sort of calculus of karma, where the practice of giving over time accrues to the offerer a certain quantity of benefit in proportion to the gift. This kind of thinking can have its problems—the Catholic practice of indulgences comes to mind. But it can also be more positively applied to action as a mode of offering, where labor in support of spirituality (like cleaning the temple or supporting the priestfolk) is itself seen as a kind of sacrifice.

What is vital is the doing: the methods are numerous and should be chosen on the basis of experimentation. The lists above are only the beginning. Animal sacrifice should be on the table at least for the meat eaters, at least once in life. (It feels to me like there is a moral obligation in there because I eat meat.) We can also remember that making offerings is not just for the Spirits and to the Gods but to teachers and leaders for honor, thanksgiving, and for their health and well-being. Iamblichus counsels that in sacrificial best practice, we remember all the beings to whom offerings should be made: we should cycle up from the local spirits, the elementals, then All the Gods, the retinue of the Deity intended, and then the Deity. You can then go on to the Creator and the One and the Void, if those are part of your cosmology. Experience has shown that the time for doing magic is right after the offering cycle (powerful!). And remember, a libation without dedication is just a spilled drink.

It is time for Pagans to restore sacrifice to its ancient and central place in our rites (and some are!). The world needs the Gods in Their fullest presence and we need to be fully present to Them if we wish our species to live in harmony with our world. The rite of sacrifice is crucial to our success. Let us restore it.

[This column was previously published here. Click through to read the original discussion.]