“Being a Christian involves living within the tradition and letting it shape our lives. It means letting these stories have their way with us.” Marcus Borg (emphasis added)

What a rich piece of storytelling is John 12: 1-8 [lectionary the week this essay was originally published]. It has everything: a familial friendship; a reference to someone being raised from the dead; the sensuality of a woman dousing a man’s feet with perfume and wiping it off with her hair; a thieving villain thick with hypocrisy; and other details, such as the description of the perfume’s heavy fragrance. Sometimes we’re so familiar with scripture we forget that much of it is simply storytelling—meant to engage and entertain us, because that is the main way we pass on knowledge. Story is how we make meaning and how we learn. Have you noticed the whole season of Lent and Easter, as with Christmas, is about telling stories?

But how are we supposed to read the stories of the Bible? The question itself gets at the struggle—because the stories of the Bible were not really meant to be read. They were meant to be heard. They were passed along by communities through group storytelling. For thousands of years before the printing press, these stories were mostly told orally and later, read aloud by people far more skilled as storytellers and story-listeners than we are. We no longer know how to do this. Our trouble comes from having too much story, from information overload. Imagine standing in a stereo shop with so many types of music playing on different speakers that you can’t hear a song long enough to be moved by it. We are like that.

So why have humans always told stories? … People haven’t so much “applied their lessons” in an intellectual way as they have been formed by them. The repetition of familiar stories, and the characters and lives people come to know through story form them into certain kinds of people. Our view of the world is formed by repeated stories. Story shows us who to be.

This past week I heard the account of a man who’d been rescued and taken in as a child when he was orphaned and threatened by the Nazis in the 2nd world war. As a grown man he was curious why certain people risked so much, risked their own lives, to take in and protect children like him. No one had to do this. So as a man, he researched the question. He found that people who risk themselves to help others had just one thing in common. It wasn’t religion, it wasn’t politics, it wasn’t wealth or poverty or any other demographic category. People who helped in a risky way did so because they believed that is just “who they are.” They did it because that is the “kind of person” they wanted to be.

And who we are, what kind of person we want to be, depends so much on the stories we hear, what examples and characters we surround ourselves with through story. In the story we read in the gospel today—one we might read many times over the course of our lives, various characters are featured. Most prominently, Mary whose devotion to Jesus is so pronounced that she behaves scandalously and bravely, anointing his feet with costly perfume and wiping them with her hair. It is a stunning portrait of love and devotion. In contrast, we have the portrait of Judas, who is looking after himself while pretending he cares about others.

Most scriptural traditions show us that the divine speaks to us through story, that we are shaped by story. It is incredible! But nothing reveals this more than the dream world. Dreams are revelatory stories. They guide us in remarkable ways, even if subconsciously or beyond awareness. Metaphor, plot, character—these building blocks of narrative are the building blocks of dreams, and astoundingly, a key language through which Spirit speaks.

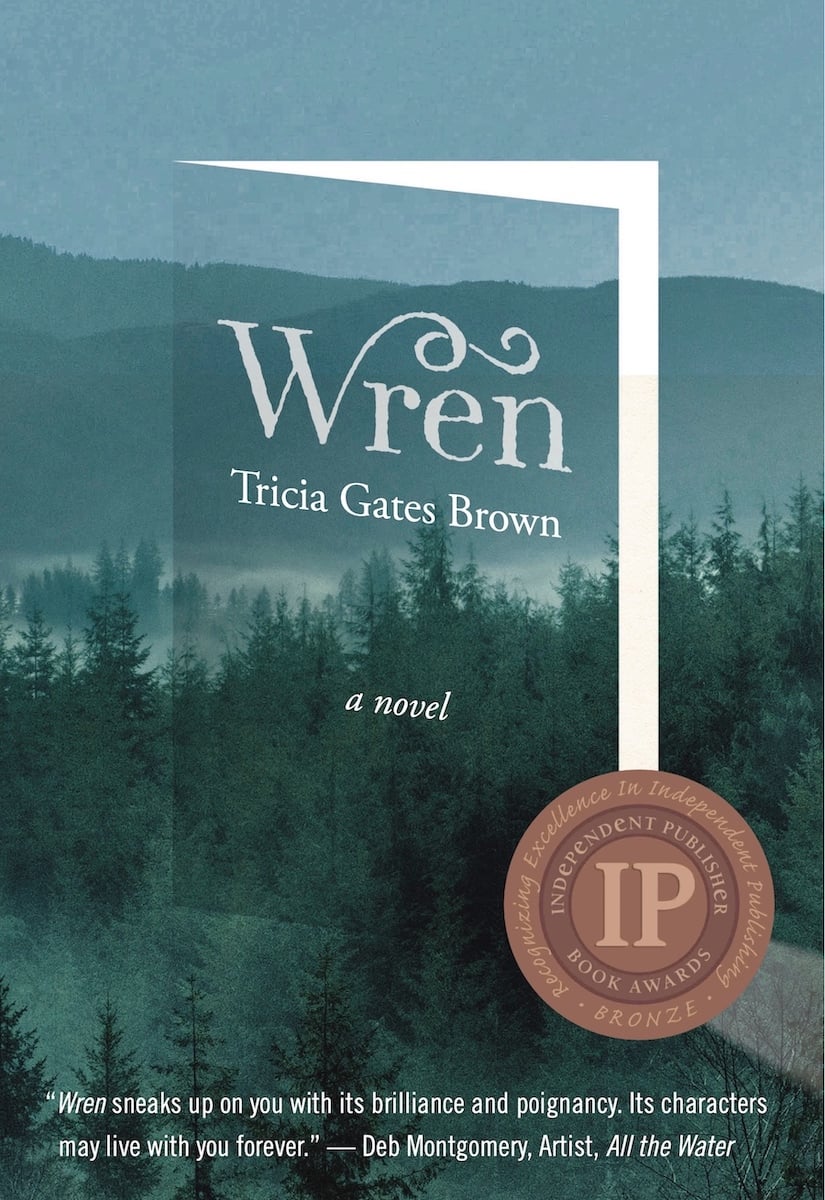

With the advent of platforms like television, home video and streaming, we have never had more story in our lives. We are surrounded by it. I relish stories in all of these forms. And the tales don’t just entertain me or distract me; they make me think. Because I have thought a lot about story, I am conscious that films/shows/books are also shaping me, determining who I will become.

It’s important then that we are mindful of story, both consciously connecting with a storytelling tradition such as scripture, or an oral or literary tradition, returning to it over and over and letting it have its way with us, but also being thoughtful about how entertainment shapes us. As we consume stories, ask: Who am I becoming because of the stories I consume? By this, I’m definitely not commending moralism; I’m not saying we should consume only what is PG-13 and stay away from sex and violence. Often I am far more disturbed by the simplistic moral universe of a cartoon on the Disney Channel, carelessly promoting the “myth of redemptive violence” (message: violence solves all our problems) and a worldview with black-and-white good guys and bad guys, than I am by dramas telling the human story in all its muddle and frailty, where violence perpetuates more violence, and we fail each other, and each of us is an amalgam of dark and light. What I am saying is that we should pay attention to the subtexts of the stories we consume, and not be naïve. These stories are creating us, they are having their way with us, especially when we consume them uncritically. Sometimes we may not see the effects until we are in crises and are put to the test—and our “characters” play out our values on the stages of our own lives. Stories and characters matter. Are the stories we surround ourselves with making us more like a Mary or more like a Judas?