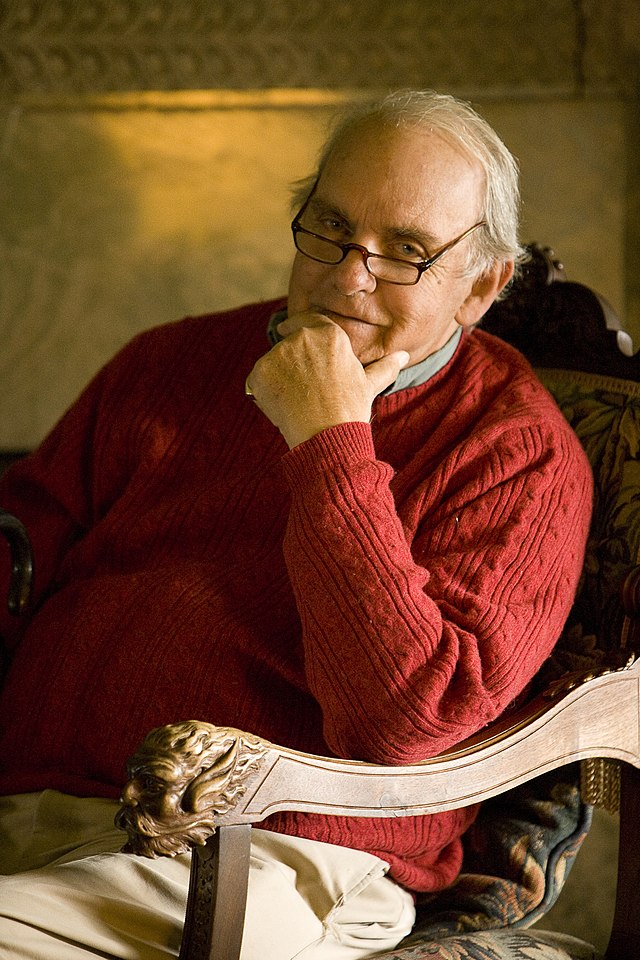

No author has impacted my life as has Frederick Buechner. Not only have I read all but two or three of his copious writings (two of his novels are among my ‘top five’: Godric and The Final Beast), but he inspired me to become a writer. Finding and reading him changed my life—the honesty, the remarkable loveliness of his writing filled me with aspiration. It still does. And the wide-open, not fussy, warm-and-hospitable God Buechner portrayed made me want to keep looking.

The following excerpt is from my memoir Jesus Loves Women: A Memoir of Body and Spirit. It tells of how I discovered Buechner. How blessed, the day.

My systematic theology professor reads aloud in class. One fall day he reads from an author named Frederick Buechner, his autobiographical trilogy. Sitting at my desk, I hear the following words in which Buechner tells of his encounter with a surprisingly down-to-earth faith healer:

“More even than our bodies, she said, it was [our] hurtful memories that needed healing. For God, all time is one, and we were to invite Jesus into our past as into a house that has been locked up for years—to open windows and doors for us so that light and life could enter at last, to sweep out the debris of decades, to drive back the shadows. The healing of memories was like the forgiveness of sins, she said” (Now and Then, p. 63).

As I hear these words, I stare at my desk and force back tears. Buechner’s words seep deep beneath my layers of guardedness, behind the bulwark I had erected to keep from remembering the hurts of my past. The words stir in me a longing for something I hadn’t even known I needed—the healing of memories.

The words linger with me all day: The healing of memories is like the forgiveness of sins. I picture God as an old woman, carefully working her way through dusty, stale rooms, humming, pulling back curtains and opening windows, whisking away the hurt and leaving rooms sunny and smelling of Murphy’s Wood Soap, leaving the memories changed and hallowed.

Within a couple of weeks, I encounter Buechner again. At the time I am cataloging books for the university library where I hold a part-time work-study job. Almost every new book that enters the library passes through my hands. One day as I work through another monotonous MARC record, robotically filling in the necessary fields on my computer screen, I notice Buechner’s name on the spine of a book halfway down my cart. The three short volumes of Buechner’s autobiography sit there, waiting to be catalogued, waiting like a treasure in a field. Since I have the privilege of signing books out before they’re processed, I take Buechner home.

I delve into those volumes of memoir the way I would relish good wine—mmm-ing over each sip, appreciating the richness—but in the case of Buechner, also weeping. Reading Buechner I feel as a child does, having done something careless or clumsy, and someone comes along to say, “Don’t worry. It’s going to be okay. Everything is okay.” In Buechner’s telling, that is like God. In his view, the only way we know God and see God is through the most ridiculous, painful, humiliating moments of our lives, because God is in those places embracing us and helping us along. God is there with the cursed more so than with the blessed. At first, I cannot read Buechner without sobbing.

Describing the way God speaks to people via the medium of everyday life, Buechner writes,

“God speaks to us in such a way, presumably, not because he chooses to be obscure but because, unlike a dictionary word whose meaning is fixed, the meaning of an incarnate word is the meaning it has for the one it is spoken to, the meaning that becomes clear and effective in our lives only when we ferret it out for ourselves” (The Sacred Journey, p. 4)

Buechner seems to revere human life, depicting everyone’s life as undeniably sacred. Love and God are there if we look for them. And wherever love is, there is God; and wherever God is, there is sacredness. Embarrassed by the mistakes of the past several years, I had walked through life like a person with voluntary amnesia. I had refused to look back for fear I would crumble under the weight of regret. The mixed-up marriage, the loss of my self and the unheeded deterioration of my confidence, the seeming waste of those years—I had blamed myself for all of it.

Buechner urges me to look back on my life not with shame but with reverence and to let God heal the memories. Years will pass before I experience more reverence than repulsion, before I experience actual healing. But it is Buechner, more than anyone else, who turns me in the right direction.

Buechner walks with me that entire year. I read volume after volume of his writing.

Thank you, friend Buechner. Thank you for writing no matter what. Rest in power.

Available HERE.