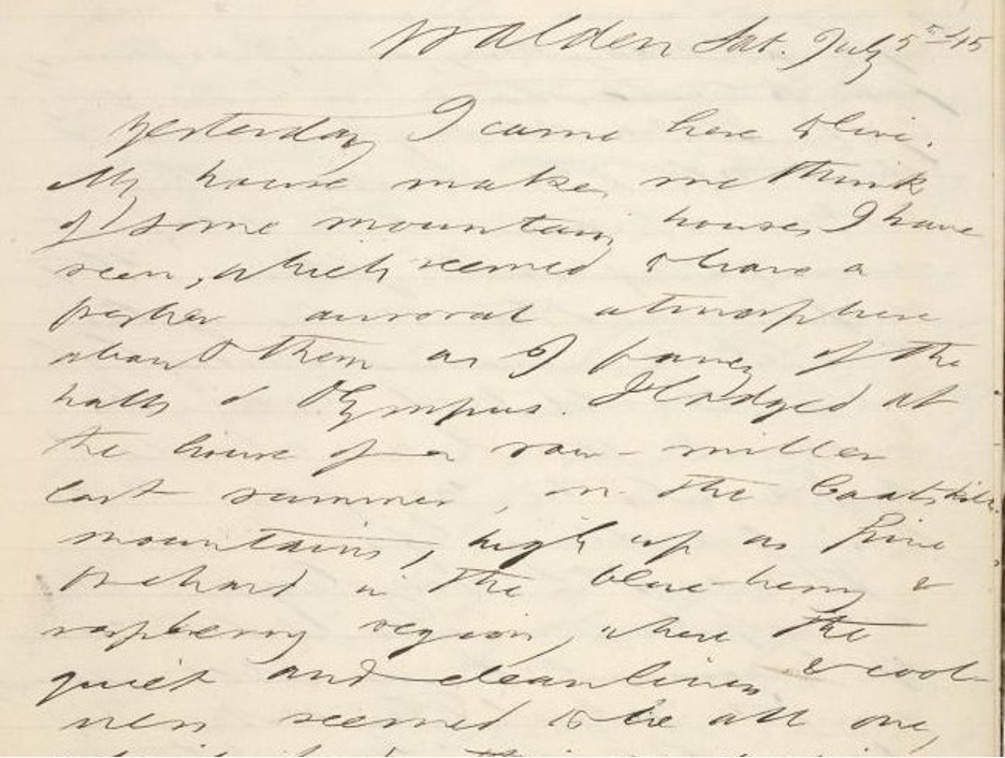

{Four years ago at this time, I was at Walden Pond. Before the trip, I wrote this reflection. While in Concord, I saw handwritten, original drafts of Thoreau manuscripts, pictured above.}

When I moved from Oregon’s Willamette Valley to the north Oregon coast in 2004, it was a leap. I parachuted out of a life that no longer accommodated into a 10-month sojourn of dis-illusionment, dismantling, and radiant transformation in a tiny Oceanside, Oregon duplex on a cliff overhanging the Pacific. The move began as a freefall. No one pushed me; I jumped. Fortunately, after a few unsteady years, I landed in 2007—feet on the ground—in a small river valley cottage I helped to build (mostly doing finish work with the help of skilled friends). Turns out many make radical life moves in similar fashion: hold your breath, leap, crash, stand and dust off and survey the new territory. Something about the ocean, in particular, invites this, beckoning those who want a life of substance and synergy with nature—a life difficult to cultivate in bustling towns. People move to such areas seeking reflection and art. We long to pare down our material belongings, our external obligations, and to attend the things that mend the soul. Ultimately, we believe this will change the world.

Then something gradually happens. Slowly our ambrosial Thoreauvian fantasies come face to face with a little reality called the economy. This perplexing imbrication is unavoidable: the shady overlap where our commitments to simplicity meet the realities of high cost of living, high rent and property values, lower paying jobs, taxes, and in the case of those who live on the coasts or similar destinations—economies based largely on tourism, shopping, and second-home ownership. Cognitive dissonance ensues.

But let’s back up to those ten quiet months in Oceanside. During 2004 to 2005, I listened to Thoreau’s Walden on audiobook repeatedly while walking the beach. At earlier times in my life I had attempted the book. Yet I couldn’t still myself enough to absorb the baroque constructions of Thoreau’s language, or to understand his message. Yet walking amidst the wild, solitary expanses of the Pacific coast, I let Walden soak into me and inspire me. The Conclusion became like sacred scripture. In fact, it’s hard not to recognize the similarities between parts of Thoreau’s Conclusion to Walden and some of Jesus’ teachings. Thoreau writes:

“However mean your life is, meet it and live it. Cultivate poverty like a garden herb, like sage. Do not trouble yourself much to get new things, whether clothes or friends. Turn the old; return to them. …Sell your clothes and keep your thoughts.”

“In proportion as he simplifies his life, the laws of the universe will appear less complex, and solitude will not be solitude, nor poverty poverty, nor weakness weakness. If you have built castles in the air, your work need not be lost; that is where they should be. Now put the foundations under them.”

“No face which we can give to a matter will stead us so well at last as the truth. This alone wears well. For the most part, we are not where we are, but in a false position. … However mean your life is, meet it and live it; do not shun it and call it hard names. It is not so bad as you are. It looks poorest when you are richest. The fault-finder will find faults even in paradise. Love your life, poor as it is.”

It was the unclutteredness, the time to “keep my thoughts,” that had drawn me to my life on the Oregon coast. But the contemplative sojourn in Oceanside was only to last ten months, just as life by Walden Pond lasted, for Thoreau, only two years. Many misunderstand Thoreau as a recluse and escapist, but we was neither. He lived his life mostly in town (all but his two years at Walden); he was largely consigned to jobs he didn’t necessary relish (for example, successively teaching, caretaking Emerson’s home and kids, helping run his family’s pencil-making business, surveying) to support vocations that while not money-making, were his life’s work (explorations in nature, writing); he was deeply engaged with his mother and sisters and the family chores, as with members of the Concord community among whom he sang, danced, argued and learned.

In coming weeks [this was written in 2018] I will be visiting Walden Pond for the first time with my grown daughter, and it feels like a pilgrimage. Anticipation rises. I have read no American writer so resonant with my longings for simplicity and transcendence as Henry David. (I say this while simultaneously repudiating Thoreau’s nineteenth-century views tainted with misogyny and racial prejudice, especially in terms used for Native Americans. Both the resonance and repudiation are true.) Thoreau encourages me to keep living the life I have chosen—even if others don’t get it. Whenever my schedule allows time for a quiet walk by wild margins, for artfulness, or a bit of time to sit and reflect, and each time the deep life and energy stir in me, I am reminded of why I choose this path. And whenever I re-read Walden passages like those above, my inner Amen-chorus rouses. Living out the truths of these passages may be easier said than done, but it is worth the effort.

Walden is often dismissed as a nature treatise by those who haven’t really read it. Yet while Thoreau does discourse stunningly on nature in the book, Walden is really a discourse on freedom—freedom of the spirit, freedom from the “lives of quiet desperation” our economic realities lead us into if we are not vigilant. We all have circumstances beyond our control that limit our choices. But Thoreau encourages readers to set ourselves free from the shackles we impose upon ourselves, in our desperation to be seen a certain way by our peers, to live up to societal expectations, to have more and more pretty things, to distract ourselves, to lazily avoid hard questions, to cloyingly grope for company and adulation. The costs of freedom may be high, but the payoff for choosing freedom is resurrection and mirth. To surrender to the mystery, we must first catch a glimpse of what awaits. We must be able to see. That is the challenge. For as Thoreau writes in the final sentences of Walden: “The light which puts out our eyes is darkness to us. Only that day dawns to which we are awake. There is more day to dawn. The sun is but a morning star.”

Thank you for supporting my work by subscribing (free).

Wren, winner of a 2022 Independent Publishers Award Bronze Medal