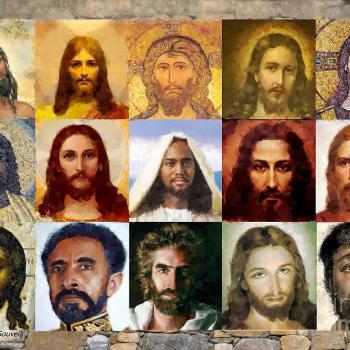

On the surface, this week’s gospel reading at the end of John (John 20:19-31) is a story about doubt and belief, and a recounting of an appearance by Jesus before his disciples. But I can’t read it without drawing in biblical studies. Because one of the key aspects of this passage is the statement “Blessed are those who have not seen and yet have believed.”

John was the last of the gospels, written many decades after Jesus’ life. The writer of the gospel and the leaders behind the Johannine community did not know Jesus. They were among those who “had not seen, yet they believed” because they did not serve as witnesses to Jesus’ life on this earth. So this story is, on an important level, about the authority of the leaders behind the gospel of John. It is saying, we may not have known Jesus, but we have just as much authority as those churches founded by the apostles! In this context, the statement “Blessed are those who have not seen and yet have believed” has a competitive ring to it. I draw attention to this not only because it’s interesting socio-historically, but because this story about “doubting Thomas” has often been used to guilt people for not believing enough, or not believing the right things. Maybe it is saying no such thing.

Trust, not “beliefs”

Increasingly in podcasts or in news stories, I hear references to the fact that Americans on the whole—especially younger people—drift away from religion. It seems every month this refrain grows louder. Maybe you notice this among people in your life or in your community. I feel strongly that an emphasis on beliefs misleads people to think that the faith life is about believing the right things—when the faith life is about love, and a mature trust in God as a benevolent presence in one’s life. We have all known people who can rattle off the right beliefs yet who put their full trust in money or might, or who rattle off the right beliefs but show very little kindness to others. Beliefs just don’t get us far in life without more important things like kindness and rootedness and trust.

But then why do liturgical traditions stand up each Sunday and recite the creed, stating what “we believe”? Especially when some of us have as much doubt as belief when it comes to various statements of the creed? In large part we do this because it is an ancient part of our tradition. The word “credo” in Latin is related to the word “heart.” In the sense of the ancient creed, to “credo” something doesn’t mean to accept it in your head. It really means to embrace it with your heart—as a part of a historical community rooted in those stories. I especially like the “we believe” language of the Nicene Creed. In saying “we believe” it defines the tradition of “us,” of our community as Christians. And we are part of this Christian community and can embrace it with our hearts even if we, like Thomas, need to experience things for ourselves before we can trust.

What I wish most for our young people is that they will be a part of close communities that will teach them kindness, encourage them in deepening trust in God, and light their paths through life so that they will develop values and character and strength for the journey. In my view, healthy faith communities do this well. They teach us how to live this life for others, and to be true to ourselves. These are the things that are important, not holding the “right” beliefs.

Wren, winner of a 2022 Independent Publisher Award Bronze Medal