{For the beginning of this series, click HERE}

A Buddhist friend once shared a technique she uses to manage stress in difficult circumstances: “walk slowly.” I have tried at times, and it helps. It is also opposite of what until recently I did under stress, when I’d rush around like I’d quickly get to peace-and-quiet if I got things done quickly. In the midst of my current flare-up of chronic illness, I’m walking slowly. It’s fairly easy to remember when each step on a hard surface sends pain through my ankles.

The other day after a nap, my husband and I watched a hummingbird at the feeder outside our bedroom window. It fluttered in place, drinking, then ascended and came back; repeat. Sharing moments like this come with slowness. When have I taken time to lay in bed and watch a hummingbird at midday except under this imposed slowness?

The disappointments of slowness

But with this necessity of slowness also comes disappointment. I am an artist and projects in my head wait to be done. Before my lupus crash, I ordered supplies for slab pottery because using my wheel took too much exertion. The box of supplies sits unopened. At times, I feel my motivation for almost everything has been sucked out of me by pain and fatigue. Those moments don’t last long, but when they come, I am devoid. I am a vacuum. Where once there was passion, now I just don’t care. Physical struggle has a way of telescoping everything down to a narrow aperture: me and my body. Though I am not prone to chemical addiction (my addictions are of other varieties), I now understand on a deeper level the constricted world of the chemically addicted. The body’s needs have a loud echo that can drown out everything else.

My future looks different to me: less travel, more paying people to do things I always thought I would do for myself. More asking for help. Some days I don’t know if I can make a couple of beds, or move a moderately heavy box, because the consequences of these small actions will be too great. Lifting a tea kettle requires both arms because of pain in my wrist. Forget the prospect of a road trip.

Yet on the outside, I look normal. As I walk through the grocery store on a rare outing—this time on my way to the pharmacy, I realize how invisible much physical suffering can be. On the outside, I look “normal,” unafflicted. If I pass someone I know and share a few words of greeting, they would have no idea I’m unwell. It raises my awareness that many people I pass while out might be physically or emotionally suffering in ways entirely invisible. Lord, have mercy, as we Episcopalians say.

“I will never have this version of me again. Let me slow down and be with her.”

{Quote by Rupi Kaur.} I am getting better bit by tiny bit, day by day. Making my way up from the low of this lupus crash/flare. But nothing will be the same after this experience. In the past I could work at something until it caused pain, then I’d rest for a few days and be back to baseline. I’ve accomplished great things this way. Now the pain is a signal throughout my body of an inflammatory process that puts my organs at risk, and my life. In this sense, the pain is my friend. It’s not something to push past, but something to heed. This friend says, “Psst, it’s time to slow down now. You’re going to hurt yourself.” And so, I do. This friend, I am recognizing, is reliable. In reading the stories of people with lupus, I recognize that a bad flare can set one back permanently. The flare I’m in now seems to have set me back permanently. The trick is to learn how to live at a different decibel, a different velocity. To proceed from here as if everything is different. Because it is. But also to learn what slowness offers.

What needs putting aside is put aside, what needs prioritizing is prioritized. On Palm Sunday I was back in church for the first time in a month, serving as deacon and preaching. The Gospel reading on Palm Sunday is very long and as I read through it, lightheadedness dogged me. I was covered in sweat and shaking. But then my bearings arrived. As I preached, so did steadiness and presence.

Back home, as I lay resting from the morning, I was overcome with gratitude and tears.

{Roughly 52% of Americans live with chronic illness. If you know someone who might benefit from this series, please share.}

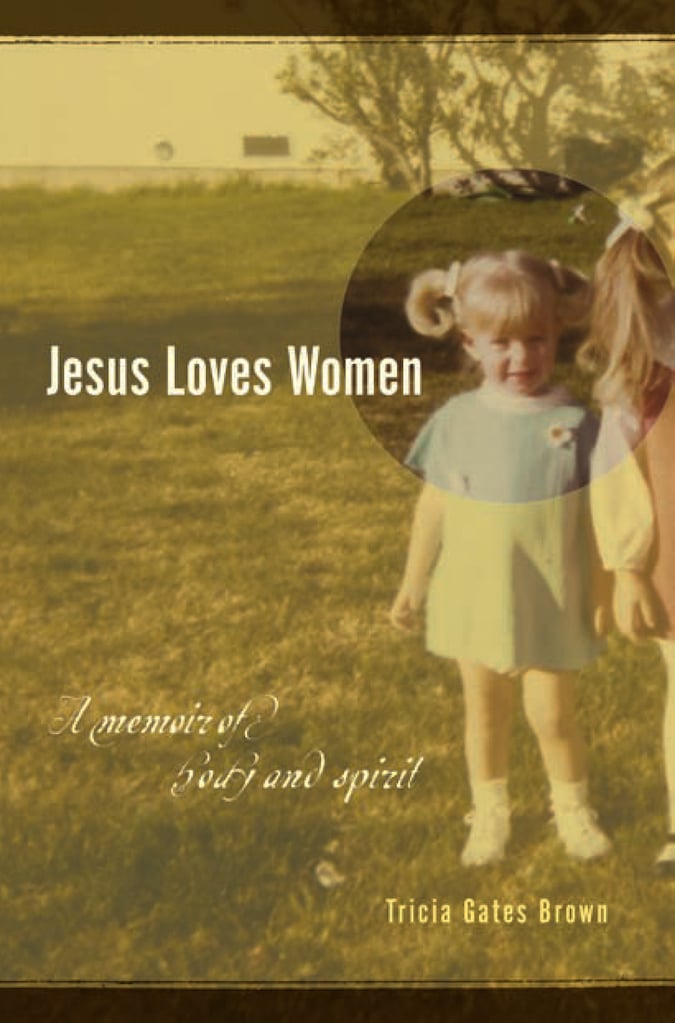

Available in paperback HERE.