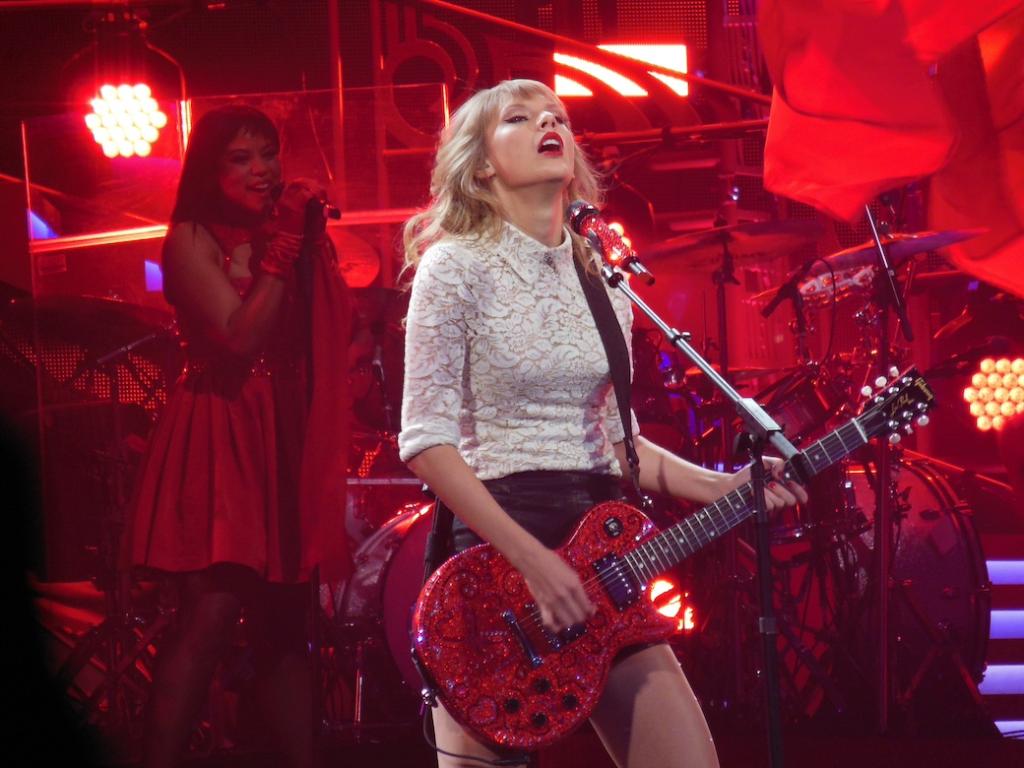

For many millennials (not to mention others), Taylor Swift is a religious experience. One such person calls me Mom. My daughter—the same age as Swift—drove the backroads of rural Tillamook County blaring Swift’s earliest albums from a beat-up sedan that won ‘Worst Car’ her senior year. To daughter Madison, Swift comes close to perfection. Deciphering the genius and intent of her songs, the closest thing she has to religion. Her attendance of Taylor’s Eras Tour last year was her observance of high holy days—almost akin to a pilgrimage as she traveled halfway across the country to attend with her best friend.

In this column, I assert that all people are religious. We all have sacred meaning systems that offer us stories, rituals, community, beliefs, and values to live by. Most of us have multiple religions, and many hold them unconsciously. Examples of “secular” religions might be football, party politics, or grandchildren. Though everyone has these meaning systems, many don’t realize they are shaped by a religion. They might think of religion in turns of dominant faith traditions, period.

As long as people’s religions are healthy for themselves and others, I have no problem with this breadth of religion. Humans have been religious since our earliest imaginings because we need meaning systems. I do regret when people are unconscious of their religions. If we are to critique our religions and fold in our doubts, we need to hold them consciously.

I don’t mind that Taylor is one of my daughter’s religions (and she does seem to hold the religion consciously). The stories, rituals, beliefs, and values she gleans from Swift’s work challenge her, make her think, evoke her powers of perception and analysis, and perhaps most importantly, move her. From formal faith traditions to basketball to political elections—emotional buy-in is clearly key to religion. One example, the Psalms. I see the power of these story-songs in their expression of the full human catastrophe and their probing for the meaning of life. At their best, the Psalms move us.

Telling Stories that Empower and Inspire Us

But honestly, most of what the Psalmist talks about, I struggle to relate to. While I appreciate the emotions expressed in the Psalms, I can be moved to tears by Taylor’s expressions of heartache; her stories of seeking connection, finding it, losing it, repeat. At the crux of her discography are stories of a rocky and disappointing love life. In a 2023 interview, she described her song-writing as sucking the poison out of a snakebite and depriving it of its power. For some, singing along with her songs has this same effect. A song from her album Midnights speaks to my experience so potently, I automatically exchange for “New York,” the word “Nehalem” because that’s where I was during the experience:

When the silence came, we were shaking blind and hazy / How the hell did we lose sight of us again? / Sobbin’ with your head in your hands / Ain’t that the way shit always ends? / You were standin’ hollow-eyed in the hallway / “Carnations you had thought were roses, that’s us” / I feel you know no matter what / The rubies that I gave up / And I lost you, the one I was dancin’ with / In New York, no shoes / Looked up at the sky and it was maroon

This song, eerily produced by Swift producer Jack Antonoff (himself, voluminously talented), sends a chill.

If people, especially young people, will have the “fight” to survive and thrive in an uncertain future, they need stories. We all need stories. Not just four second stories we see scrolling through the reels of social media, but stories we hear over and over, and that we see ourselves in. The heart of religion is storytelling. Sacred stories help us see ourselves in a narrative much larger than our own small struggles.

People who follow Swift see her rising up in an exploitative industry to re-record her entire discography, wresting control of it from an exploitative label. They see her pouring herself into creating when she could otherwise be broken, to make something beautiful out of tragedy. They see her overcoming an early eating disorder, touring with her mother and keeping close her true friends over decades, admitting her vulnerability and frailties (see interview link above). So too, her probing of self-doubt and her quest for self-understanding, for understanding her own role in the relationships that fail. They see her writing songs about her grandparents and honoring where she came from. In all of these things, they are empowered and inspired by her stories in the ways we are all empowered and inspired by religious narratives. That’s why it’s important to choose those narratives carefully.

I still remember walking into Sierra Sound Records at 17 to purchase U2’s Joshua Tree album on the day it came out, the memory tinged with ambrosial light because of my heightened anticipation of it. As a youth, following that band, being inspired by the worldview of their main songwriter Bono—in particular, his railing against violence and his fervor to find meaning while increasingly awash in power and materialism—shaped me as a young person more than any religion. U2’s anthem, “I Still Haven’t Found What I’m Looking For,” grew up with me, an exquisite expression of the roller coaster of faith, of the quest for meaning in a sometimes nihilistic, vacuous culture. I understand my daughter’s religious adherence to Swift because I felt that way about U2, and still love the band. When I first heard that song, I cried. It was so perfect, so evocative of things inexpressible in my young heart—doubt of the meaning system I’d been given, permission to begin my own quest for what is real.

I never did see U2 in concert. When my daughter saw Taylor Swift , I was smiling.

Wren, winner of a 2022 Independent Publishers Award Bronze Medal

Winner of the 2022 Independent Publisher Awards Bronze Medal for Regional Fiction; Finalist for the 2022 National Indie Excellence Awards. (2021) Paperback publication of Wren , a novel. “Insightful novel tackles questions of parenthood, marriage, and friendship with finesse and empathy … with striking descriptions of Oregon topography.” —Kirkus Reviews (2018) Audiobook publication of Wren.