GAGE ASKS:

Is killing as a protection of the United States, like going into the Army, a sin?

THE RELIGION GUY ANSWERS:

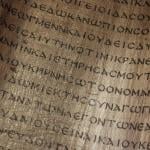

Adequate treatment of this classic issue would require thousands of words. But start with some venerable quotations: “Do not kill or injure living creatures” (typical wording from Buddhism’s Five Precepts). “You shall not kill” (from the Bible’s Ten Commandments). “Do not kill the living soul which Allah has forbidden you to kill, except for a just cause” (Islam’s Quran 6:151).

Very broad-brush, religions have generally accepted military service alongside those teachings, and the killing it inevitably involves, as justified for self-defense, protection of others, public safety, and other social values, although faiths usually also contain groups that favor total pacifism.

Mark Juergensmeyer, an expert on this history, surveys Asian religions as follows. India’s Jainism is strictly devoted to non-violence, to the extent that followers even avoid killing vermin. Hinduism cherishes ahimsa (Sanskrit for “no harm”) yet its culture has not been pacifist over-all, though it abhors killing animals to eat because people have other food options. Buddhism has been even stronger on ahimsa, yet Buddhist regimes have often considered armies necessary, limiting strict non-violence to monks (and note unpleasant modern ethnic conflicts against Hindus in Sri Lanka and Muslims in Myanmar). Sikhism takes pride in its military heritage. Islam accepts violence considered justifiable, as we see in newspapers every day, though non-violence is preached by some Sufi mystics and the Ahmadiyyas (deemed heretics by the orthodox).

The Jewish Bible countenanced warfare, but with ambiguity. God declared the great King David unfit to build the Temple because he was a warrior with blood on his hands (1 Chronicles 28:2-3). Some say Deuteronomy 17:16 tells Israel not to establish a large standing army. The prophets portrayed a peaceable kingdom as God’s ideal. After biblical times, Jewish minorities usually lacked the means for military activity till modern Israel arose.

Christianity presents even more complex history. The angels at Jesus’ birth proclaimed “peace on earth,” much like the Hebrew prophets. In the Sermon on the Mount, Jesus taught, “Do not resist one who is evil” and “love your enemies” (Matthew 5:39,44). When Peter raised a sword to protect him, Jesus declared that “all who draw the sword will die by the sword” (Matthew 26:52).

Christian pacifists take those words literally. But the majority believes Jesus was speaking about personal relationships, not local police work, national security, or international conflicts. Hawks note that Jesus didn’t rebuke a centurion over his vocation, Peter didn’t require Cornelius to quit the Roman army to be baptized (Acts 10), and New Testament epistles teach obedience toward rulers and regimes.

Historians William Klassen and Hans Lietzmann say that after New Testament times there was strong if not total opposition to believers serving in the military, expressed by major church fathers like Tertullian and Origen. A complicating factor is that Christians shunned the Roman army because soldiers had to take idolatrous loyalty oaths to the divine emperor. The earliest texts that portray Christians in military service concern prayers by Rome’s “thundering legion” in A.D. 174. But Klassen says very few believers were in uniform till the 4th Century.

There was dramatic and permanent change after the Emperor Constantine was baptized in 326 and Christianity emerged as an official faith responsible for public order. In that era the theologian-bishop Augustine built upon the Roman sage Cicero to develop moral criteria for waging “just war.” In the 13th century, Thomas Aquinas said war is always sinful, and yet occasionally moral.

When Protestantism appeared, total pacifism was revived by marginal Anabaptists (today’s Mennonites, Brethren, and Amish) and then the Friends (“Quakers”). The Seventh-day Adventist Church later developed a half-way view, recommending that draftees refuse to bear arms and instead join the medical corps.

The Catholic Church’s catechism defines the standard Christian stance. It states that “love toward onself” is moral so a personal right to life justifies self-defense. And defense becomes “a grave duty for someone responsible for another’s life, the common good of the family, or of the state.” Therefore Christian tradition acknowledges “the right to repel by armed force aggressors against the community.” With just cause, public officials “have the right and duty to impose on citizens the obligations necessary for national defense.” Soldiers are hailed as “servants of the security and freedom of nations” who “contribute to the common good of the nation and the maintenance of peace.” However, governments should honor those who in conscience cannot bear arms and provide them alternatives.

Writing in the dovish “Christian Century” magazine, ethics professor Martin Cook of the U.S. Army War College adds that Christians shouldn’t volunteer if their nation “routinely uses soldiers in ways that are not justified.” That doesn’t mean officials have to be “omniscient or infallible or even morally pure,” he says, but requires service to “a relatively good state led by reasonably competent and responsible leaders.”

All very commonsensical. Problem is, power politics can easily submerge ethical niceties on initiating and conducting a “just war.” And can “pre-emptive” strikes foster peace? Modern Christian ethicists say devastating modern technologies compound the moral dangers. Some apply Augustine to say Christians should be “selective pacifists,” for instance participating in World War Two but not the Vietnam War. Religious writers dispute conflicts that continually break out, while some question whether the American Revolution was justified.

And in this centennial year, will someone please explain World War One?