IRA ASKS:

Both Jews and Muslims lay religious claim to Jerusalem’s Temple Mount / Noble Sanctuary, which has long been at the center of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. What is the basis of their competing claims?

THE RELIGION GUY ANSWERS:

This uniquely and deeply revered religious site in the eastern sector of Jerusalem’s Old City is called the Temple Mount by Jews and the Haram al-Sharif (“Noble Sanctuary”) by Muslims. Smithsonian magazine says this tract “has seen more momentous historical events than perhaps any other 35 acres in the world,” while The Economist magazine considers it “one of the world’s most explosive bits of real estate.”

That second assertion has been amply underscored in recent months. An expert at the U.S. Institute of Peace tells huffingtonpost.com that the Israeli-Palestinian conflict “has developed a religious character that was not as explicit in the past.” This has been the most troublesome period for the holy site since 2000 when Ariel Sharon, campaigning to be Israel’s prime minister, boldly entered the area with a large entourage and sparked the Palestinians’ second intifada.

A pivotal incident occurred October 29, the attempted murder of Yehuda Glick. He’s an activist with the Temple Mount and Land of Israel Faithful, which seeks to upset a delicate status quo and allow Jews to pray on the mount. This movement further vexes Muslims by campaigning for Israel to rebuild a Jewish Temple there as soon as possible. Though that hope is expressed in Judaism’s daily prayers, pious tradition holds that the Temple should only arise after the Messiah comes. (One Protestant faction also dreams of a new Temple, to accompany Jesus Christ’s Second Coming.)

Such an unlikely project would invite holy war because the Haram is the third holiest place in Islam after Mecca and Medina. It is believed to be the location from which the Prophet Muhammad ascended to the presence of God during his Night Journey. Temple construction would presumably require demolition of existing Muslim buildings there, an exceedingly offensive proposal.

A famous event there some 4,000 years ago unites and divides Jewish and Muslim tradition. The two faiths agree that this was where God tested the patriarch Abraham’s devotion by commanding him to sacrifice his son, after which God did not require that deed and provided an animal substitute. In the Bible the son was Isaac, a forefather of the Jews, whereas in Muslim tradition it was the Arab forefather Ishmael.

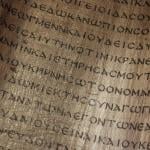

Moving forward a thousand years or so, this was where the biblical King Solomon constructed the first Temple, which was later destroyed by the Babylonians. A 1929 guidebook for Muslim pilgrims said this Temple location is “beyond dispute,” but no Muslim would admit that today. The Temple was rebuilt after the Babylonian exile and turned into a far grander edifice under King Herod beginning in 19 B.C.E. The Romans leveled the second Temple in 70 C.E. after a Jewish revolt and it has never been rebuilt. The Western Wall, a remnant of the foundation to the mount, became a sacred place for Jewish pilgrimage and prayer.

Muslim history in Jerusalem began with the conquest in 637 C.E. During subsequent decades Muslims built on the Haram their elegant Dome of the Rock, which commands the landscape, and the nearby Al-Aqsa Mosque. The Dome if not other buildings would presumably have to be leveled to make way for a new Temple, though some think the Temple was located somewhat to the north.

From the founding of modern Israel in 1948 till 1967, when Israel captured the Old City in the Six-Day War, the site was within the nation of Jordan and Jews were forbidden to visit either the Western Wall or the mount. When Israel gained control of the terrain it sought to aid interfaith harmony by handling only external security, with continued administration of the Mount / Haram by the local Muslim Waqf (charitable body). To accommodate renewed Jewish prayers at the Western Wall, Israel cleared away housing and created a large plaza. But rabbinical authorities ruled that Jews should not enter the mount itself lest ritually impure people accidentally tread on the unknown exact spot of the Holy of Holies, the most sacred precinct of the former Temple.

Today, the Waqf allows Jews (and Christians) to enter the mount, but they are forbidden to pray, and officers keep a close watch for prayer books or moving lips. Some Jews defy the rule by pretending to talk on cellphones. More and more Jews are demanding the right to pray there, and a bill to that effect has been introduced in Israel’s parliament.

The conflict is also journalistic. The conservative Media Research Center assailed a sizable November 23 New York Times roundup on the Jerusalem religious tensions, calling the piece “Exhibit A” that proved “the idea that the paper is balanced in its Israel coverage is a sad joke.” Meanwhile, The Economist insists that Israel maintain the prayer ban and “yet again make clear that the religious status quo on the Temple Mount will not change.”

A 2010 Palestinian Authority report rejected the belief that the Western Wall is an authentic Jewish holy site, saying it “was never part of the so-called Temple Mount,” while a former Palestinian chief justice has declared that the Wall “belongs to Muslims alone” and Jews “have no right” to pray there, much less on the mount itself. Palestinians are upset not only over Jewish prayer demands and the dangerous Temple rebuilding proposal but complain that Israel restricts permits for Muslims from the West Bank and Gaza to enter the Haram, and often prohibits young men for security reasons. After the Glick shooting, Israel briefly barred everyone from the compound. Jordan withdrew its ambassador in protest, and Palestinian leader Mahmoud Abbas accuses Israel of leading the region toward a “religious war.”