DAVID ASKS:

Most of us in the U.S. are aware of Orthodox Christians but don’t really understand their organization. Can you expand on their split around the world?

THE RELIGION GUY ANSWERS:

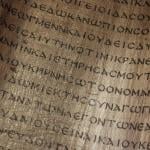

Our previous Q and A about Islam’s founding Sunni – Shi’a split mentioned divisions within Orthodox Christianity. Orthodoxy, which means “correct teaching,” sees itself as preserving Christianity’s earliest and most authentic form. This faith is in the spotlight what with 1) history’s first meeting between a Catholic pope and a patriarch of Russia’s massive Orthodox church, and 2) the June 16 – 27 “Holy and Great Council” of all bishops in Crete, potentially Eastern Orthodoxy’s most consequential event in more than 12 centuries.

Writing online February 10, sociologist Peter Berger (a Lutheran) said through recent centuries this faith has existed mostly in three contexts: as a state religion, as a “persecuted or barely tolerated” church under Islamic or Communist rule, or in the diaspora outside its heartland (e.g. in the U.S.) where separate and competing churches under foreign hierarchies generate “ethnic cacophony.”

Orthodoxy is organized into three branches that stem from the 5th Century debate on how to define the divinity and humanity of Jesus Christ. Caution: This gets technical. The Assyrian Church of the East, with 200,000 followers at most, is centered on dangerous turf in Iraq and Syria. Assyrians are called “Nestorians,” a disputed term taken from Patriarch Nestorius, who was deposed by the Council of Ephesus (A.D. 431) because his party rejected as heresy the Virgin Mary’s title “Mother of God” and prayed instead to “the Mother of Christ our God.”

Nestorians were further accused — they said wrongly — of believing Jesus Christ exists as two separate persons, not one person of two natures, divine and human. In 1994 Pope John Paul II and Assyrian Patriarch Mar Dinkha IV deemed this a misunderstanding in a “common Christological declaration” that the Savior’s “divinity and his humanity are united in one person, without confusion or change, without division or separation.” Full text: www.vatican.va/roman_curia/pontifical_councils/chrstuni/documents/rc_pc_chrstuni_doc_11111994_assyrian-church_en.html

A second branch, “Oriental Orthodoxy,” claims tens of millions of believers among the 283 million Orthodox of all types counted by the Center for the Study of Global Christianity. This is no unified body but a category of separated bodies with a shared doctrine of Christ, chiefly the Armenian (Christendom’s first national church), millions of Ethiopians and Egyptian Copts, Syria’s “Jacobites,” and a “Malabar” segment in India.

This branch emerged when the Council of Ephesus (A.D. 451) further defined Christ’s two natures, divine and human. Those who affirmed only one nature are called “monophysites,” a term Oriental Orthodoxy dislikes. The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church (which guided this entire answer) says such theology “covers a variety of positions, some capable of orthodox interpretation.”

In 1973 the Catholic Pope Paul VI and Coptic Pope Shenouda III jointly issued the “common declaration” that in Jesus Christ “are preserved all the properties of the divinity and all the properties of the humanity, together in a real, perfect, indivisible and inseparable union.” Full text: www.vatican.va/roman_curia/pontifical_councils/chrstuni/anc-orient-ch-docs/rc_pc_christuni_doc_19730510_copti_en.html

The third branch, what we call “Eastern Orthodoxy,” upheld the doctrines of Chalcedon and the six other ecumenical councils through A.D. 787, alongside Catholicism. But the Eastern churches and western Catholicism drifted apart and excommunicated each other in 1054 over the Roman papacy’s authority claims and rewording of the Nicene Creed. Eastern Orthodoxy’s 2016 Council could join Catholicism in seeking closer relations with Oriental Orthodoxy, already improved in certain situations.

Eastern Orthodoxy consists of 14 national churches that are “autocephalous” (with their own “heads,” that is, self-governing) with honorary leadership of the hierarchy’s “first among equals,” Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew of Constantinople (i.e. Istanbul). He has no pope-like authority over the others (and Oriental Orthodoxy lacks any such presiding figure). Bartholomew leads Turkey’s small flock. There are the other ancient sees of Jerusalem, Antioch (Syria), and Alexandria (Egypt), the huge Russian church (Constantinople’s perennial rival), and the churches of Albania, Bulgaria, Cyprus, Czech Lands & Slovakia, Georgia, Greece, Poland, Rumania, and Serbia. (Constantinople disputes Russia’s grant of autocephaly to a 15th entity, the Orthodox Church in America).

Bartholomew summoned leaders to Switzerland in January for final Council planning. Three church heads were absent, two for health and one for unspecified personal reasons; will they make it to Crete? Work toward a common calendar proved too difficult to pursue. Antioch’s delegation boycotted the meeting’s Divine Liturgy service due to its dispute with Jerusalem over geographic jurisdiction. Antioch also opposed draft texts on marriage law (as did the Georgians) and rules of procedure for the Council.

This dissenting body, formally the Greek Orthodox Patriarchate of Antioch and All the East, has a North American subunit based in New Jersey, the Antiochian Orthodox Christian Archdiocese. Its leader, Metropolitan Joseph, was among nominees the Americans proposed but had to be appointed by bishops in his native Syria. Ten American “canonical” ethnic branches are subject to such Old World ties alongside the O.C.A. with its disputed status. Berger thinks this “almost bizarre structure” hinders New World outreach.

There’s a worse tangle in Ukraine, with three competing Orthodox bodies that emerged from the Communist era, plus the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church with similar traditions that aligned with papal Catholicism in 1595. Troubled relations with such “Uniate” Catholics, and with Catholicism otherwise, are on the June Council agenda. But nettlesome disputes and rivalries within Eastern Orthodoxy may well prove tougher to handle.