THE QUESTION:

Can we rely upon New Testament texts that were copied and recopied over centuries?

THE GUY’S ANSWER:

It’s hard to think of any question more central for the Christian faith than that. The Catholic Church’s Second Vatican Council and subsequent catechism proclaim that the New Testament books provide “the ultimate truth of God’s revelation.” The church “unhesitatingly affirms” that they “faithfully hand on” the “honest truth about Jesus” and the history of his words and deeds.

Yet consider this. If people were to be asked what’s their favorite saying of Jesus Christ, many would certainly choose his words while being executed upon the cross: “Father, forgive them; for they know not what they do” Luke 23:34). Equally cherished is his admonition to the mob preparing to stone to death an adulterous woman: “Let him who is without sin among you be the first to throw a stone” (John 8:7).

Careful Bible readers will note that most Bible versions on sale today, including those produced by conservative evangelicals, have footnotes stating in all candor that those two sayings are absent in early and widely recognized Gospel manuscripts in the original Greek language. That does not prove the sayings are not authentic but that it’s possible or likely they weren’t in the two Gospels as originally written.

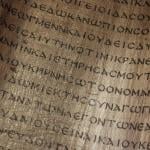

The familiar King James (Protestant) and Douay-Rheims (Catholic) translations from centuries ago raise no such questions. But today’s Bibles note such findings from modern-day scholarship in the highly technical field of “textual criticism,” which seeks to get us as close to the original writings as possible. The fact we have around 5,300 surviving manuscripts and fragments, a few of them quite early (vastly more evidence than with other 1st Century writings), means experts must evaluate and choose from many variations.

This situation led to doubts about New Testament credibility from a respected textual critic, Bart Ehrman of the University of North Carolina, in a scholarly work, “The Orthodox Corruption of Scripture” (1993). He then popularized his thinking for general readers in the best-selling “Misquoting Jesus: The Story Behind Who Changed the Bible and Why” (2005). New Testament books were copied and recopied by hand and Ehrman says in the process scribes made not just “accidental” but “intentional” changes. (Experts like Ehrman dismiss conspiratorial nonsense about this in novels like The Da Vinci Code from 2003.)

Similarly, an overblown 2015 Christmastime article in Newsweek contended that “at best” Bible readers have “a bad translation — a translation of translations of translations of hand-copied copies of copies of copies of copies, and on and on.” Yes, much depended on the accuracy and skill of copyists who distributed the holy writings across the ancient Mideast and replaced texts on papyrus or parchment as they deteriorated. The same is true, of course, with all ancient writings.

In the latest round, such challenges against the New Testament are analyzed in the anthology “Myths and Mistakes in New Textament Textual Criticism.” The co-editors are Elijah Hixson (Ph.D., Edinburgh) of Tyndale House, an evangelical Bible research institute near Cambridge University, and Peter Gurry (Ph.D., Cambridge) of Phoenix Seminary.

They and the 13 other contributors represent a rising generation of conservative, well-trained experts in these matters who defend the New Testament’s trustworthiness while honestly admitting problem areas, and write with clarity so we non-specialists can follow the action. The Guy here can only skim this rich material about scribal work and manuscript evaluation, so readers interested in these intricacies should buy the book.

This is a courageous step for InterVarsity Press, an evangelical publisher. Sure, the authors poke holes in fashionable skepticism from Ehrman and others. But simultaneously they criticize fellow evangelicals for distorting the realities and skirting the problems, and say such defenses have a boomerang effect that can make knowledgeable readers question Scripture’s credibility.

The introduction by Gurry and Hixson says “misinformation abounds.” The book does not argue whether the New Testament claims about Jesus are true but treats the preliminary question of “whether we can know what those claims are.” Leaving aside spelling variations, we learn, there are roughly half a million total differences among all the Greek manuscripts that specialists sift, or perhaps 1 percent of the New Testament. The authors say well-established techniques can securely trace the history of the texts.

In summary, the book contends that “the textual evidence we have is sufficient to reconstruct, in most cases, what the authors of the New Testament” wrote and “convey the central truths of the Christian faith with clarity and power” as the basis for “robust” Christian faith. The vast majority of differences are said to be trivial and do not touch central beliefs but the book honestly admits “doubt remains significant” with a couple dozen passages. Here are two important examples.

Most scholars think Mark was the first gospel to be written. Famously, three competing versions of the ending have come down to us. But the very beginning is equally puzzling. Most Bibles render the very first verse as “The beginning of the gospel of Jesus Christ, the Son of God,” with a footnote saying some ancient manuscripts omit “the Son of God.” The issue here is not whether Mark believed in Jesus’ divinity, which is taught throughout the book, but whether this was proclaimed at the start or meant to emerge as the story unfolds.

Then here’s one example Ehrman uses in his scenario that scribes purposely rewrote the Scriptures, which makes them unreliable. John 1:18 says “no one has ever seen God. It is God the only Son, who is close to the Father’s heart, who has made him known” (NRSV translation). Instead, some texts say “the only God.” Ehrman theorizes that scribes fiddled with the origiinal text to fight off the idea that God only adopted Jesus as his son during his life, as opposed to eternal divinity. The new book contends this “adoptionist” heresy did not emerge so early and that grammar argues for the other reading.

With Scripture, one little word or phrase can make a big difference.