THE QUESTION:

What are the long-term trends for the world’s religions? What’s the situation in China?

THE RELIGION GUY’S ANSWER:

Broad-brush, Christianity remains the world’s largest and most widespread religion and will still be so in 2050 thanks to steady growth in “Global South” nations of Africa, Asia, and Latin America. But Islam is steadily gaining ground. Declines relative to the population have been suffered by folk religions in China, tribal traditions elsewhere, and the ranks of the non-religious. In 1800, Christianity and Islam together represented a third of the world population but these outreach-oriented faiths will encompass a projected 64 percent by 2050.

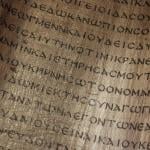

All that and much more is reported in the newly published third edition of the World Christian Encyclopedia (Edinburgh University Press, 998 pages, $215.95), compiled by the Center for the Study of Global Christianity at Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary, an evangelical Protestant school in Massachusetts. It was edited by the center’s Todd Johnson and Gina Zurlo, who led a team of 40 along with hundreds of expert consultants across the globe.

The encyclopedia contains unique statistics and analysis on each religious group that exists within each of the world’s 234 nations and territories, with elaborate information on cultural groupings and 45,000 Christian denominations. Quite obviously, this monumental reference work belongs in every serious library in the English-speaking world.

Here are the estimates comparing major religions’ size as of 1970 with their current numbers.

Christians: Grew from 1.2 billion to 1.99 billion, maintaining a stable proportion of nearly a third of the world’s population.

Muslims: From 570.5 million to 1.3 billion, expanding from 15.4 percent to 21 percent of the global population.

Hindus: From 463 million to 822 million.

Agnostics: From 544 million to 656 million (a somewhat shrinking percentage of the population, while atheists have actually declined in number, from 155 million to 141 million).

Buddhists: From 235 million to 452 million.

Chinese folk religionists: From 238 million to 431 million.

Other ethnic religionists: From 169 million to 224 million.

There are much smaller numbers for global adherents of the various new-born religions, and for Sikhs, Spiritists, Jews, Daoists, Confucianists, Baha’is, Jains, Shintoists, and Zoroastrians (“Parsis”).

Within Christianity, the researchers list the ten largest “families” of church members in this order: Catholics in the “Latin Rite” (as opposed to Eastern Rites), proliferating Pentecostal and Charismatic groups, other Evangelicals, the Eastern Orthodox, Anglicans & Episcopalians, Baptists, “united” church bodies, the “Oriental” and other Orthodox, Lutherans, and Presbyterian & Reformed Protestants.

The volume’s major scenario is the way Global South nations have emerged as the population center of the Christian religion after long dominance by Europe and North America. Remarkably, as of 1900 some 18 percent of Christians lived in the Global South compared with 67 percent today and a projected 77 percent by 2050. Africa is now the continent with the most Christians, having surpassed Latin America in 2018, which had surpassed Europe in 2014.

This southward dynamism is seen in foreign missions. Of the world’s 425,000 cross-cultural missionaries, 143,000 are being sent out from North America, but simultaneously other countries have sent 46,000 workers into North America. We see the same pattern in Europe. The most important sources of workers from the developing world are Brazil, Nigeria, and South Korea.

For an example of the work’s 234 detailed, country-by-country articles, let’s summarize the depiction of China. Since Communism took power in 1949, the world’s largest nation has experienced mass-scale death and major political, economic, and religious turbulence. Only faiths registered by the government are supposed to hold worship and then only those in the five recognized categories of Buddhist, Daoist, Muslim, Catholic, and Protestant.

Among Christians, there’s a long-running split between those that accept the required registration and oversight by the atheistic regime vs. those that refuse this in principle, including a profusion of somewhat or totally secretive “house churches” that are obviously hard to count. (The same with millions of “hidden Christians” in countries like India, where it can be wise to keep such belief private and maintain a Hindu image in public.)

The encyclopedia figures that China’s officially registered “Three-Self Patriotic” Protestants number 30 million. House churches in the dominant Han ethnicity encompass 39.5 million; they have been hit with renewed government crackdowns since 2018. Catholicism, much smaller, shows a similar two-way split. In all, China has 106 million Christians in 60 subgroups. (Thus churchgoers outnumber Communist Party members even though that credential is necessary to obtain good educations and jobs in the countless institutions and businesses the regime controls.)

The Communist government has gone back and forth on whether to try to exterminate religion, or only persecute religious believers, and if so how viciously, or simply leave them alone. The Communist-era constitution permits freedom for “normal religious activities,” though that leaves open what particular area authorities might deem to be “normal” at any moment.

Chinese folk religion, a complex mixture of spiritual elements and traditions such as veneration of ancestors, originally suffered greatly under the Communists’ mass anti-religion campaign, then underwent another wave of persecution during Mao’s destructive Cultural Revolution (1966-69).

In 1982, the regime adopted a more tolerant policy toward all faiths. Two other important traditions, Confucianism and Daoism, both loosely organized and hard to control, experienced similar ups and downs. They are currently somewhat in favor as a means to foster cultural unification.

Buddhism has experienced special rehabilitation so that its followers now number 237 million. But Communism attempted to wipe out the distinct ethnic form of Buddhism in Tibet led by the Dalai Lama, murdering many monks, seeking to secularize most others, and demolishing more than 1,000 monasteries.

Islam fared somewhat better than other faiths during the Cultural Revolution, though mosques were generally shut down. But the religion now experiences systematic suppression of believers in non-Han ethnic groups, especially the Uighurs in western territories.

Coronavirus willing, the Gordon-Conwell center plans an interesting-looking conference about its new research September 28 – October 1 at the Massachusetts campus. For details, e-mail [email protected].