THE QUESTION:

Should religion influence U.S. public policy? For instance, look at Protestants.

THE RELIGION GUY’S ANSWER:

The media occasionally press this question upon us as, as with a timely May article by Religion News Service columnist Jeffrey Salkin titled “Should religion influence abortion policy?” His thinks not. Salkin acknowledges that “religious ideas are part of the public discourse” but even so “those ideas cannot determine policy. Public policy must be open to rational discourse, with provable data, and not merely rely on beliefs, however sacred their sources.” (Naturally, pro-lifers would reply that they rely on “rational discourse” and “provable data” from biology.)

He continues, “America does not allow you to turn your own religion’s theological ideas into public policy. . . . This way lies chaos, and worse — holy wars between religious groups. This way lies a return to the Middle Ages. It is time for all religious people to call: Time out.” For Salkin, this approach is required by freedom of religion — or perhaps should we say freedom from religion?

Salkin champions the pro-choice public policy advocated by this own faith, Reform Judaism, which puts this among 17 causes on the agenda of its Washington lobby. The pro-lifers believe laws should protect the tiny human life growing in the womb. Faiths such as Reform Judaism oppose such protection, believing that women must exercise unimpeded abortion choice. To a journalist, religious alliances on both sides seek to impose their belief as public policy,

Whether America’s religious groups should try to influence policy, they’ve in fact done so since Plymouth Rock and will continue to under the Bill of Rights. Reminders. As much as anything it was Christian zeal that led to abolition of slavery — and 620,000 Civil War deaths. Similarly with the colonists’ rebellion against Britain, women’s vote and, in a remarkable demonstration of Protestant power now mostly regretted, nationwide alcohol Prohibition written into the Constitution.

Which brings us to very important but oft-neglected history depicted convincingly in the new book “Before the Religious Right: Liberal Protestants, Human Rights, and the Polarization of the United States” (University of Pennsylvania Press) by University at Buffalo historian Gene Zubovich. As the title indicates, media treatments and political agitation since 1979 or so have concentrated on religious conservatives. But liberal Protestants, who’ve been steadily losing steam since the mid-1960s, exercised outsize political influence across the preceding half-century.

Leaders’ engagement was whole-hearted, whether or not ordinary parishioners necessarily agreed. There’s something of the same dynamic today. Scholars tell us that alongside vocal national conservatives, at the local level evangelical congregations are the least politically active segment of American religion, in comparison with Catholics, Black Protestants, white “mainline” Protestants and a collective category of non-Christian faiths. See www.getreligion.org/getreligion/2020/9/21/evangelicals-are-actually-americasleastpoliticized-group-of-churches/ Back in the liberals’ heyday, in fact, the predecessors of today’s religious right continually .criticized liberal Protestants for pushing politics to the neglect of soul-winning.

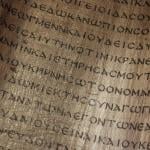

Here we must pause to define what today is called “mainline” Protestantism, this book’s focus, over against the evangelicals (who also form factions within “mainline” groups). These denominations originated in Colonial times and the early Republic. They are predominantly white, relatively affluent, tolerant in theology and easily identified by membership in the Federal Council of Churches and, after 1950, the successor National Council of Churches. Zubovich flatly calls these churches “liberal” and usually refers to them as “ecumenical Protestant.”

As of 2022 the most prominent “mainline” bodies are American Baptist Churches, Christian Church (Disciples of Christ), Episcopal Church, Evangelical Lutheran Church in America, Presbyterian Church (USA), United Church of Christ and United Methodist Church (which is beginning a sizable schism over the Bible and sexuality). Their predecessors were America’s unofficial religious and educational establishment from the founding till well into the 20th Century.

The power-brokers in the golden era before 1970 are often forgotten today except to some extent theologian Reinhold Niebuhr. Zubovich tells us about other players like Niebuhr’s seminary colleagues Henry Van Dusen and John Bennett, Methodist Bishop G. Bromley Oxnam, Methodist women’s leader Thelma Stevens and Congregationalist executive Douglas Horton., Especially intriguing are two attorneys, Presbyterian John Foster Dulles (yes, later Ike’s secretary of state) and Episcopalian Charles Taft (the president’s son).

The substance of this research is too complex to easily summarize here, but just a couple themes. Without question, ecumenical Protestants’ proudest achievements were rallying behind international human rights, leading to the great 1948 Declaration of the United Nations, and the later struggle to defeat America’s racial Jim Crow and segregation.

Reluctance to enter World War II is thought of today as a right-wing, what with America First, Charles Lindbergh and anti-semitism. But a powerful segment of liberal and pacifist churchmen hated war and preached isolationism till Pearl Harbor, just as idealistic preachers believed the 1928 Kellogg-Briand Pact would simply end war by making it illegal. The influential Christian Century even looked for economic benefits from the National Socialist conquest of France. Many later were optimistic about the Soviets and lamented the Cold War mentality (Dulles by then had turned hawkish).

It’s common but a bit unfair to say an author should have written a somewhat different book. Still, The Guy would have welcomed key brief comparisons with Catholicism, for instance the way the 1919 Bishops’ Program of Social Reconstruction, formulated by priest-sociologist John Ryan, anticipated much of the FDR Democrats’ New Deal. Zubovich bypasses heavy theological disputes that explain liberal-evangelical competition. And given the book’s subtitle, it very much needed a final chapter bringing the story through liberalism’s slide up to evangelicalism’s ‘ current political morass.