THE QUESTION:

In Islam, what is a fatwa? Why the demand to kill novelist Salman Rushdie?

THE RELIGION GUY’S ANSWER:

In 1989, the Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, Iran’s theocratic ruler, ordered the assassination “without delay” of novelist Salman Rushdie because of his novel “The Satanic Verses.” Remarkably, this official fatwa imposed the duty of freelance killing in the name of God upon masses of Muslim believers in all nations, and also demanded death for the editors and publishers involved with the book.

Three decades later, a Lebanese-American stands accused of attempting to murder Rushdie by repeated stabbings onstage at New York’s Chautauqua Institution. The author suffered severe injuries but survived. Though the Muslim Council of Britain condemned the attack, the Iranian regime’s Kayhan newspaper dispatched “a thousand bravos” to “the brave and dutiful” assailant while militants in other Muslim lands celebrated. We’ll see what prosecutors and defense attorneys finally say about links between Iran’s fatwa of death and the sensational bloodshed.

Rushdie’s complex fantasy had dream sequences in which depraved enemies of Islam — not the author himself — complain about moral absolutism and treatment of women and demean the Prophet Muhammad’s wives and closest Companions. They also challenge the divine inspiration of the Quran. A Wall Street Journal op-ed correctly noted that the far greater threat to the Quran is the revisionist theorizing on its origins by the late John Wansbrough at the University of London.

The Rushdie novel resulted in book-banning and riots in the Muslim world, and the famous fatwa sent Rushdie into hiding for years. In 1998, Iran’s president declared the case “finished” during diplomatic efforts, but the regime did not actually abolish the fatwa. It was reaffirmed by Khomeini’s successor as Supreme Leader in 2017, and re-published on a government Web site five days before the Chautauqua stabbing. During the past decade, Iranian groups have pledged to pay a $3.9 million bounty to anyone who slays Rushdie.

What should not get lost in the tumult is that Khomeini rewrote the definition of what a fatwa can be in modern-day Islam. And though his policy was opposed by devout individuals and groups, no effective, wholesale condemnation of the new concept has been established across global Islam.

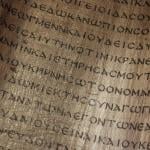

In Islamic tradition, a fatwa is simply a formal ruling by a recognized authority on a question that has not been decided by existing religious law (Sharia) and jurisprudence (fiqh). Most often, believers ask for decisions on specific personal matters that arise in limited circumstances. Myriam Renaud of DePaul University says a fatwa might address, for instance, hygiene, marital relations, job decisions, inheritance, lifestyle matters, or what allegiance believers owe to their nation, and “rarely” calls for execution. These rulings are distinct from the criminal law and court procedures of Islamic governments, which may involve the death penalty.

In certain strict Muslim nations, perceived blasphemy against God and his Prophet, and apostasy from the faith, are considered crimes subject to death, which creates continual controversial cases. But Khomeini turned untold millions of ordinary Muslims into potential self-assigned assassins who should kill the apostate anywhere on earth. Theoretically, that could inspire a deranged extremist to execute, for instance, Barack Obama. The former president, who converted to Christianity, is regarded legally as a Muslim, and therefore an apostate, because his (non-religious) father was Muslim.

This vigilante order still in force ignores Islam’s established justice and trial procedures. It seeks to slay not just an individual Muslim seen as a traitor to the faith but non-Muslims who worked on the book, which provoked a murder in Japan and attempted murders in Italy and Norway. By reaching far beyond Iran into Muslim communities everywhere, the fatwa roused hysteria about Sharia and damaged the religion’s stature in democracies that uphold freedoms of conscience, speech, and press.

Khomeini’s critics within Islam saw no basis in the Quran for his policy and in fact the opposite. When people mocked the faith, God through Scripture advocates patience or else withdrawal of association (see 3:186, 4:140, 10:44, 41:34, and 45:14). Verses that express hostility occur in contexts of combat, they contend. On this, consult commentaries in The Study Quran (HarperOne, 2015), edited by Seyyed Hossein Nasr of George Washington University.

What, then, might justify Khomeini-style vigilante justice? Militant Muslims can cite one precedent in the authoritative Hadith collections of the Prophet Muhammad’s words and deeds. He asked for volunteers to kill the Jewish poet Ka’b ibn al-Ashraf because he “hurt Allah and His Apostle” (Sahih al-Bukhari, book 64, #84). Mustafa Akyol of the Cato and Acton Institutes says reformist Muslims think the poet was executed not just for insulting Muhammad but for inciting polytheists to warfare against the young Muslim movement. Akyol cites two other Hadith traditions in which Muhammad was lenient toward scoffers.

Aykol says Muslims take three main stances on blasphemy. Today’s “extremist” policy agrees with Khomeini that anyone who insults Islam and especially Muhammed deserves death, even if carried out by vigilantes. Targeting of non-Muslims is legitimate, for instance the 17 murders in 2017 at the office of France’s satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo.

The “mainstream conservative stance,” embraced by all four Sunni schools of legal thought and by Shia jurists, also considers “insulting the Prophet” a capital crime, but punishable “only by courts, with due process, not by terrorism or mob violence.” There’s disagreement whether repentance can remove punishment.

Aykol advocates the third, “reformist” Muslim view that insults are “morally reprehensible” but cannot be treated as crimes. He contends that “the right Muslim response is either to counter criticisms with reason or to ignore sheer vulgarness with dignity” because this gains “respect for our faith” and demonstrates confidence in it.