NICHOLAS ASKS:

In the New Testament, Acts chapter 8 says that Simon Magus “believed” and then was baptized. But he was not saved. Does this teach us there’s a gap between mental assent and change of heart? Or what?

THE RELIGION GUY’S ANSWER:

The intriguing figure known in Acts 8 as just Simon was later designated “Simon Magus,” which helped distinguish him from the Bible’s other Simons. His name led to the sin called “simony,” the corrupt buying or selling of spiritual powers, benefits, or services.

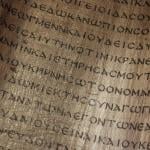

In its earliest phase, the Christian movement was centered in Jerusalem and entirely Jewish in membership. Acts 8 depicts the new faith’s very first missionary venture, Philip’s visit to neighboring Samaria. The Samaritans were despised by Jews due to historical enmity and their quasi-Jewish religion. For instance, the Samaritans regarded only the first five books of the Bible (the Pentateuch or Torah) as divine Scripture, and did not believe in the future coming of the Messiah.

Philip’s preaching was accompanied by miraculous healings, which won the attention of Simon, who had “amazed the nation” with his magic performances. We’re told that Simon described himself as “somebody great” (thus that “Magus” moniker) and that people thought “the power of God” was at work through his magic.

As Samaritans began accepting Philip’s message to follow Jesus Christ, “Simon himself believed, and after being baptized he continued with Philip.” That must have caused quite a stir. But – believed what, exactly?

The apostles in Jerusalem then dispatched Peter and John to Samaria, where they laid hands on the new converts who “received the Holy Spirit.” This passage underlies the Catholic, Eastern Orthodox, and Anglican belief that ministers must be formally set apart by the laying on of hands, in a line of “apostolic succession” that traces back to Jesus’ original founding apostles.

The Acts passage also inspires Pentecostalism’s belief that an infilling or “baptism” with the Holy Spirit is a necessary experience separate from conversion and water baptism. Non-Pentecostals think other Bible passages indicate that all water-baptized believers in Jesus Christ have God’s Spirit, for instance Romans 5:5 and 8:9 and 1 Corinthians 12:13. We’ll leave aside those ecclesiastical debates and turn to Nicholas’s topic.

Simon offered to buy spiritual “power” so that people he himself laid hands on would receive the Holy Spirit. Peter denounced Simon for this “because you thought you could obtain the gift of God with money. . . Your heart is not right before God. Repent therefore of this wickedness” and pray that “if possible the intent of your heart may be forgiven you.” Simon responded, “Pray for me to the Lord that nothing of what you have said may come upon me.”

So, was Simon only pretending to be a Christian believer in hopes of gaining authentic spiritual powers instead of magic trickery? Or was he a sincere convert, yet unformed and trapped in old ways of thinking?

Or, as Nicholas proposes, did he have a merely intellectual knowledge of what Christians taught without a change of heart and a true commitment to follow Jesus as his savior? After all, the demons depicted in Mark 1:21-28 stated as a fact that Jesus was “the Holy One of God,” and James 2:19 says that “even the demons believe – and shudder.”

A related issue across the ages is whether Simon regretted this and was authentically Christian even though seriously mistaken. The Acts passage about Simon’s sorrow seems to imply that he repented. If so, did he backslide later on? Christian legends following New Testament times said Simon became a noted and well-traveled heretic. In the 2nd Century, the “Simonians,” a heretical Gnostic sect in the Mideast, revered this magician as their founder. Christian authors came to treat Simon Magus as the forefather of all heretics.

Catholic exegete Joseph Fitzmyer said Acts 8 has this message for Christians: “Salvation is not dependent solely on faith and baptism but on one’s conduct too, and even more on one’s desires. These can lead to ‘perdition.’ “

Among Protestant interpreters, Britain’s William Neil thought that “clearly his conversion had been no more than skin-deep.” Another Brit, F.F. Bruce, wrote that “theologians may discuss whether or not [Simon] exercised ‘saving faith.’ Although (for a time at least) he ‘continued with Philip,’ Peter judged that the root of the matter was not in him. Perhaps he was simply convinced of the potency of the name of Jesus when he saw the mighty works wrought by its means.”

James Montgomery Boice, a scholarly Presbyterian pastor in Philadelphia, had a somewhat different slant on what he admitted was “a puzzling story,” in Acts: An Expositional Commentary (1997). Was Simon an authentic convert “or was he just carried along by his enthusiasm for Philip, professing something that had not really happened in his heart?”

Boice said “the easiest answer is that Simon was not a true believer.” However, it’s possible to think otherwise, since nothing in the text necessarily excludes that Simon may have been a true, if mistaken, Christian. Boice thought it “just possible” he truly believed but judged that it’s more likely “he did not have that genuine change of heart.” So “we can apply the story either way.”

Yet another possibility. What if Simon “was not a believer, though he thought he was”? For Boice, that’s “a warning to anybody who thinks that just because he or she has made profession of faith or has gone through certain motions expected of Christians that he or she is right with God for that reason.” Something to ponder.