THE QUESTION FROM VINCE AND OTHERS:

How can people believe God is both loving and all-powerful — for instance when a dread disease spreads worldwide?

THE GUY’S ANSWER:

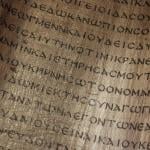

This quandary has challenged religious thinkers and troubled suffering believers from the Bible’s ancient Book of Job through modern-day reflection on the Holocaust and Covid-19. It’s infinitely above a journalist’s pay grade, so The Guy will only skim what a few people have said and are saying about this topic known as “theodicy.”

Literary scholar and lay Christian author C.S. Lewis (who died on the same 1963 day as John F. Kennedy) set up the dilemma as follows in his classic The Problem of Pain, written in 1940 when the imperiled British nation faced devastating death and destruction.

“If God were good, He would wish to make His creatures perfectly happy, and if God were almighty He would be able to do what He wished. But the creatures are not happy. Therefore God lacks either goodness, or power, or both.”

In his response, Lewis proposed that we need to carefully define “omnipotence” because God cannot do intrinsically impossible things. Remember the dormitory bull session question of whether God can create a rock so heavy He cannot lift it. Or, in this instance, cannot create a pain-free world while simultaneously granting sinful humanity free will. Lewis also sought to re-define our concept of goodness from a more cosmic point of view.

Not easy stuff to fathom, despite Lewis’s deceptively clear language, and impossible to summarize here. This was merely an intellectual argument and as Lewis honestly recounted in “A Grief Observed,” he himself could not blithely escape spiritual turmoil years later when his own beloved wife died.

An oft-quoted Lewis sentence catches us up short: “Reflect for five minutes on the fact that all the great religions were first preached, and long practiced, in a world without chloroform.” Imagine undergoing amputation without anesthesia like people did for centuries! “If the universe is so bad, or even half so bad, how on earth did human beings ever come to attribute it to the activity of a wise and good Creator?”

(Lewis saw here a strong argument against the atheism he formerly embraced. The fact that humans believe situations are unjust shows that supernatural reality underlies humanity’s inborn sense of right and wrong, which empirical science cannot explain.)

The question in the headline above is the title of a book by popular evangelical writer Philip Yancey. The Guy views it as among the best attempts to help workaday Christians try to comprehend suffering. Yancey is especially intriguing in showing that pain is essential to life and health, and in telling about people who stared down their sufferings and professed belief.

Like all writers on theodicy, Yancey offers no snappy solutions but does find partial explanations in the laws of nature and humanity’s free will and mysterious Fall into universal sinfulness. But he denies that God “directly causes suffering to teach us specific lessons.” (Remember those preachers who claimed 9-11 was God’s punishment for America’s sins?)

Methodist Bible scholar Ben Witherington blogged similar thinking this week, quoting 1 Kings 19:11-12, where “the Lord was not in the earthquake” and “was not in the fire.” He asserted that “you cannot read the will of God from natural disasters” such as Covid-19, and those who say otherwise are “false prophets.”

One approach is to sidestep the problem altogether. Oddly, that’s the case in this week’s interview with Pope Francis in Commonweal magazine. The interviewer, British theologian Austen Ivereigh, discussed environmentalism and economics but didn’t use the opportunity to ask the pontiff how he’d try to explain God’s nature and will amid the pestilence afflicting Italy and the world.

Others cope with this by believing God is something less than all-powerful, for instance with Rabbi Harold Kushner’s 1981 best-seller “When Bad Things Happen to Good People,” written in the wake of son Aaron’s suffering and death. In a salon.com interview about Covid-19, his view was affirmed by Rabbi Kara Tav, the spiritual care manager at a hard-pressed New York City hospital. She says God “created a world of inflexible laws” and disease is not “in any way part of some grand design on God’s part… God is as outraged by it as we are.”

Here are some other reflections from recent days.

Jesuit James Martin in Religion News Service: “In the end, the most accurate answer is that we don’t know. The question for believers is, Can you believe in a God that you don’t understand?”

Ephraim Radner, historical theology professor at the Anglicans’ Wycliffe College in Toronto, said the Bible “is riddled with the deepest of uncertainties, often signaled by the question ‘who knows?’ It is a question that both unveils our fundamental ignorance as creatures and, in that revelation, turns us to the dizzying grace of God in the place we actually live.” The biblical Psalms insist, “bad things keep happening, bad people keep pressing their will, bad things gnarl the mind and the heart.”

This being Holy Week, Christians naturally sought comfort in thoughts of Jesus’ death on the cross, for instance geneticist Francis Collins, who leads all federal virus research and clinical trials as director of the National Institutes of Health, interviewed at www.biologos.org: “We Christians have to recognize our story has been a story of suffering. This is not the first time nor will it be the last…. We serve a suffering Savior. If we think our suffering is unmatched by any other creature, we have only to think about Jesus.”

Similarly from attorney-journalist David French of thedispatch.com: “As Paul prophesied, ‘creation itself will be set free.’ That redemption comes through a messiah who came to this earth, experienced the full weight of evil in spite of his holiness, and then triumphed over death, the ultimate manifestation of physical decay. As Christians suffer, they worship a God who suffered also.”