Because the church doesn’t understand sin very well, we don’t forgive very well.

It’s actually worse than it sounds.

The church has become a self-appointed gatekeeper, denying grace to individuals and groups who act, identify, or feel in ways we label “sinful.” Under misguided attempts to establish orthodoxy (right ideas) and orthopraxy (right practices), we have sometimes failed at orthocardia (right-heartedness).

When the church decides what is and isn’t sinful, we become legalists. And since the church has made sin about the law instead of good and evil, the world we have been called to reach falsely believes God’s love is conditioned upon a set of laws.

Consequently, God is misunderstood to be an all-controlling force that rules a universe filled with transgression and tragedy. Blaming God isn’t just a societal phenomenon, it is learned behavior perpetrated by the church upon the world. Instead of love, the church heaps guilt upon our members and others, and so traditional churches in North America are failing—deservedly, I might add.

But God’s love is the means and the purpose of our relationships with God and one another.

This is the essence of atonement, a subject I will share more about in coming weeks. But before we explore the role of God’s love in a theology of atonement, we should first re-evaluate how we think of sin.

Fire Codes

I used to think of sin as if it is fire.

In my mind, I imagined that sin, like fire, could be simultaneously beautiful yet destructive—and that it could spread insidiously just about anywhere, anyplace. A spark, seemingly innocuous on its own, could become a holocaust laying waste to both the innocent and guilty.

My reasoning also had much to do with the consequences of sin: the proverb is true, if you play with fire, sooner or later you will get burned—but equally of note is that such wounds inevitably leave a mark, a scar.

That word, scar, always gave me pause. Coming from the Greek ἐσχάρα (eskhara), meaning “place of the fire,” it seemed like an apt metaphor for how I believed sin could change us in a seemingly permanent way.

All of this dovetailed nicely with how I was taught about sin growing up in the church. Similar to the classical Augustinian definition, my church characterized sin with a specifically Wesleyan qualification as “willful transgression against a known law of God.”

Such legalistic terminology remains prevalent even today. And sure, James 4:17 definitely connects sin to misapplied free will, and 1 John 3:4 describes sin as lawlessness. But these verses really only describe what sin lacks, ultimately telling us only what sin is not.

Equally legalistic and opaque are Reformed definitions proposing sin to be any moral failing that deviates from God’s divine laws, whether by act or omission. Which is not altogether removed from the best of Catholic hamartiology (the study of sin), which forwards that sin is an utterance, deed, or desire that offends God.

Meanwhile, all traditional Christian views distinguish original sin from personal/actual sin. Although it may seem useful to specify how humanity’s inclination towards sin differs from how sin is committed, these considerations are in any event more an exploration of application, not constitution.

Judaism has similar distinctions, however sins committed between humanity and God are more easily atoned for than acts committed against other people. As with Christianity, sin can be categorized multiple ways within Judaism, but all are violations of God’s commandments. The primary Jewish/Old Testament definition of sin revolves around the Hebrew word חֵטְא (het), which is a term borrowed from archery meaning “to miss the mark.” Humanity’s inclination towards evil is called יֵצֶר הַרַע (yetzer hara), a shorthand Hebrew term connected to imagination.

Overall, traditional definitions tend to overcomplicate categories, types, and penalties of sin, while oversimplifying the nature of sin itself into confoundingly vague legalism.

The problem with all of these interpretations is that if sin was merely something that can be easily quantified, it does not account for the progressive nature of evil on an individual and global scale. If transactional violations of heart and/or deed are all there is to sin, then similarly, God’s love is reducible to a formula of good conduct rather than relationship.

And that’s not only contrary to human experience, its bad theology.

I’m not saying traditional definitions of sin are necessarily wrong…but they are fragmentary and unclear—shallow both in meaning and biblical scholarship.

In a word, inadequate.

Let’s Start from Scratch

Scripture actually presents a robust, dynamic view of sin, one that suggests much more than the narrow interpretations that often proliferate the church.

For example, believers and non-believers alike typically perceive sin to be an external force of temptation vying for their will. I certainly did—like a mesmerizing fire I could approach but not touch lest I get burned. Such doctrines have been responsible for leading some to even blame God for sin.

But Jesus taught that sin has a much different source:

“It is what comes out of a person that defiles. For it is from within, from the human heart, that evil intentions come: sexual immorality, theft, murder, adultery, avarice, wickedness, deceit, debauchery, envy, slander, pride, folly. All these evil things come from within, and they defile a person.” (Mark 7:20-23, NRSVue)

We ourselves bear responsibility for sin because it comes from our own hearts. God did not create humanity to serve as robotic code enforcers—so the freedom we have to desire a heart that loves like God also enables us to choose evil.

Jesus said that even the intention or desire to commit acts such as theft, murder, and adultery is sin. If we were to create a definition of sin that is biblically informed, we must include that we are vulnerable to sin because of our own desires, an attraction to evil.

James 1:13-15 reinforces this:

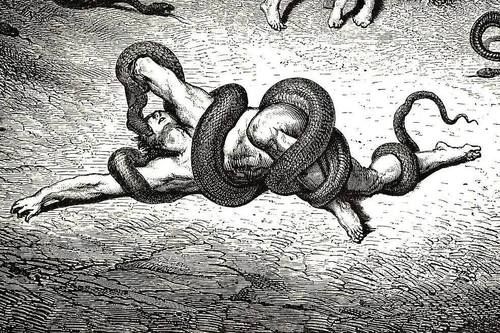

“When tempted, no one should say, ‘God is tempting me.’ For God cannot be tempted by evil, nor does he tempt anyone; but each person is tempted when they are dragged away by their own evil desire and enticed. Then, after desire has conceived, it gives birth to sin; and sin, when it is full-grown, gives birth to death.” (NIV)

Besides establishing unequivocally that God is not responsible in any way for temptation, sin, or evil of any kind, this passage presents a clear progression of the consequences of sin. Interestingly, the author of James describes the trajectory of evil in terms of seduction and strategy. Our working biblical definition of sin must include this pervasive characteristic of sin, and its final result: death.

The word pervasive comes from the Latin term pervadere, a verb meaning “to spread throughout.”

This is described in more detail in Galatians:

“For what the flesh desires is opposed to the Spirit, and what the Spirit desires is opposed to the flesh, for these are opposed to each other, to prevent you from doing what you want. But if you are led by the Spirit, you are not subject to the law. Now the works of the flesh are obvious: sexual immorality, impurity, debauchery, idolatry, sorcery, enmities, strife, jealousy, anger, quarrels, dissensions, factions, envy, drunkenness, carousing, and things like these. I am warning you, as I warned you before: those who do such things will not inherit the kingdom of God.” (Galatians 5:17-21, NRSVue)

While this passage offers a list similarly to the Markan passage we examined earlier, what is more important for our purposes is that it clarifies the pervasive progression described in James—eventually, sin spreads in a way that deprives us from connecting with God, because sinful desires are “opposed to the Spirit.”

The significance of the mutually exclusive dynamic between sin and the Spirit presented here cannot be understated. The Spirit is what connects us with God: this life-giving love-giving connection is holy because God is holy and the Spirit is holy, and sin prevents us from desiring this connection.

In his letter to the Romans, the Apostle Paul narrates his personal experiences losing ability to connect with God because of sin:

“So I find this law at work: Although I want to do good, evil is right there with me. For in my inner being I delight in God’s law; but I see another law at work in me, waging war against the law of my mind and making me a prisoner of the law of sin at work within me. What a wretched man I am! Who will rescue me from this body that is subject to death? Thanks be to God, who delivers me through Jesus Christ our Lord! So then, I myself in my mind am a slave to God’s law, but in my sinful nature a slave to the law of sin.” (Romans 7:21-25, NIV)

Paul laments the inner conflict between the desire to do good and the inclination towards sin. This struggle is depicted as a force that separates individuals from a harmonious relationship with God, reinforcing the idea of sin as a pervasive attraction to evil.

This also suggests a proto-framework for atonement: though we are unable to extricate ourselves from sin, we are still delivered by God through Jesus.

A New Definition

Let’s review the characteristics of sin we identified from scripture:

- Sin comes from within us, beginning as an attraction to evil.

- Sin is pervasive.

- Sin deprives us of holy connection with God.

- Sin results in certain death.

Therefore, I propose the following definition of sin:

Sin is a pervasive attraction to evil that deprives us of holy connection with God, resulting in our certain death.

This definition emphasizes the inherent struggle between human nature and divine morality, seeking to examine the spiritual consequences of succumbing to sinful inclinations.

Comparing this definition to more mainstream interpretations of sin, such as transgressions against a moral code or divine commandments, reveals a distinctive emphasis: while traditional definitions often focus on specific actions deemed morally wrong, my definition broadens the scope to include the underlying attraction to evil. This shift encourages a deeper introspection into the motivations behind sinful behavior, acknowledging that the pervasive nature of this attraction may not always manifest in overt transgressions.

This definition asserts that sin is not a checklist of forbidden deeds but a conflict against the allure of evil. It recognizes the subtleties of sin, urging individuals to confront the inner forces that hinder their connection with God. This perspective aligns with the teachings of Jesus, who emphasized the importance of purity of heart and intention (Matthew 5:8), suggesting that sin extends beyond outward actions to the innermost thoughts and desires of our hearts.

Furthermore, my definition offers a bridge between traditional theological concepts and psychological insights. By framing sin as a pervasive attraction to evil, it acknowledges the complexities of human psychology and the constant battle between our higher moral aspirations and baser instincts. This resonates with the psychological understanding of the human condition, acknowledging the inherent tension between our virtuous ideals and the alluring pull of darker impulses.

This definition presents a comprehensive perspective that encompasses both biblical teachings and contemporary insights. It widens the lens through which we view sin, emphasizing the internal struggle against the attraction to evil and encouraging a holistic examination of one’s spiritual condition. While traditional definitions focus on actions, my proposal delves into the root of sin and offers a deeper understanding of human experience in relation to divine morality.

The Heart of the Matter

To a world filled with tragedy and evil that believes Christianity is showing up for a scheduled service and following a list of don’ts, by contrast, the definition of sin I have proposed presents an opportunity to have a life filled with authentic loving relationships. Literally, it’s life over death—a pure heart rather than technicalities and legal judgements.

And that is important: as Christ-followers, we can ascend beyond legalism and farfetched expectations of human perfection to perfect love that casts out fear, a heart that loves unconditionally and without reservation.

It’s a mission to vanquish generational guilt and condemnation by accepting and treasuring others within the reach of our hearts with the same heart, mind, soul, and strength we love the Lord our God. Your life can be a gift of grace.