Faith on Film is a monthly feature published the last Sunday every month.

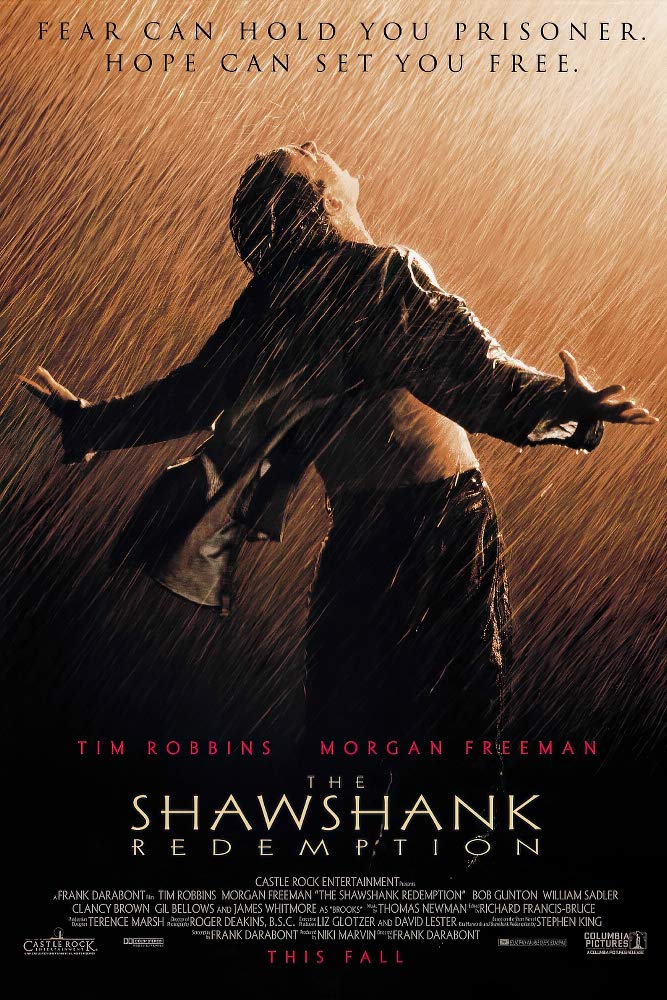

More than an amazingly entertaining, moving, well-crafted film, The Shawshank Redemption is also a manifesto against the dangers of institutions and the people who become their victims. It is a film the church needs to rewatch with new eyes, especially on Resurrection Sunday.

The Plot

In case you are one of the few who have never seen the film, The Shawshank Redemption follows the journey of Andy Dufresne (Tim Robbins), a banker wrongly convicted of murder, as he navigates life in Shawshank State Penitentiary. The story is primarily told through the eyes of Red (Morgan Freeman), a seasoned inmate known for his ability to smuggle goods into the prison.

Upon his arrival, Andy befriends Red and proves himself to be resourceful, using his financial skills to assist the guards and fellow inmates alike. Despite facing abuse from other prisoners and the corrupt warden, Norton (Bob Gunton), Andy maintains his dignity and hope for freedom.

Throughout the course of the film, we meet other inmates at Shawshank. One example is Brooks (James Whitmore), an elderly man who struggles to adjust to life outside the prison walls after being released on parole. Andy also befriends a clumsy young thief named Tommy (Gil Bellows), who he tutors to get a GED.

Andy’s activities within the prison walls include managing the prison library and helping Norton with his financial schemes. He also covertly works on a project that captivates the curiosity of his fellow inmates, sparking rumors and speculation about his true intentions.

As the years pass, Andy’s resilience and determination inspire those around him, including Red, who begins to believe in the possibility of redemption. Despite the challenges and setbacks, Andy’s unwavering spirit offers a glimmer of hope in the darkest of places.

Here is the film trailer:

Andy

This has always been one of my favorite films, and it probably is for many of you reading as well. It certainly is popular: it has been the #1 film on IMDb’s user submitted top 250 list since 2008.

It’s critical reevaluation over the past thirty years has led to many in the Christian faith community comparing protagonist Andy Dufresne to Jesus, and there is some validity to that comparison:

- Andy’s wife was unfaithful, as we, the bride of Christ, have been.

- Andy is plunged into a hopeless world or darkness, corruption of death.

- Andy is innocent, yet convicted anyway.

- Andy constantly works to encourage others to enjoy a life of freedom, beauty, hope, and love despite their surroundings.

- Andy subverts the rules of the powers that be to accomplish his goals.

- Andy descends into the worst imaginable hell to rise triumphant.

- Andy’s cell is empty the next morning, creating mass confusion.

- Despite all the warden’s schemes, Andy owned all his assets the whole time.

- Andy provided Red with the means to accept the gift of freedom Red was given.

- Andy is waiting to spend a life of freedom with Red when he arrives.

Certainly Andy uses weaknesses in the prison system to share beauty and educate his fellow inmates.

One such example is an amazing scene when Andy is given phonograph records by the state, and he locks himself in a room with the prison PA system, a record player, and a copy of Edith Mathis and Gundula Janowitz singing Mozart’s The Marriage of Figaro. The whole prison population freezes in place when they hear the beautiful singing, experiencing perhaps the most beautiful sounds that had ever graced their ears. Even when the guards threathen to break down the door, Andy looks through the window at them, and turns up the volume.

Andy’s clever fearlessness in transforming the lives of others is exactly how Jesus subverted religious leaders and their traps to offer freedom outside the rules of the Pharisees to anyone who had ears to hear.

But Andy’s true legacy lies in how he helps other inmates; in fact, although Andy is the main protagonist, the audience only sees him through the eyes of other characters. Like Jesus, Andy doesn’t just make friends, he makes disciples. He took people of different backgrounds, experiences, and personalities, and made them like himself.

What makes The Shawshank Redemption interesting however isn’t how Andy’s circumstances and actions could parallel allegorically with Jesus, but how others in the film have the same struggles many believers today encounter because they are imprisoned by the institutional church.

Brooks

When elderly inmate Brooks is released on parole, he struggles to function in the real world. “In here he is an important man, an educated man,“ says Red. “These walls are funny. At first you hate them, then you get used to them. When enough time passes, you get where you depend on them. That’s institutionalized.”

Brooks resembles believers I have known who spent the majority of their lives within the institution of the church, and their entire faith experience is synonymous with scheduled church services. The institution of a building, a pastor, corporate prayer, singing songs, and hearing a sermon became the sole manifestation of their connection to God.

In the film, forty-nine years of institutional life at Shawshank robbed Brooks of his ability to connect with others and experience love. He feels alone and unappreciated even when he is surrounded by others. When he writes a letter to the inmates he left behind, he notes that even the bird he released from prison was able to fly away and thrive, yet he himself cannot.

In Brooks’ final moments, he reverts back to institutional habits, treasuring the same things, such as attendance, that are prioritized in places such as prison or traditional churches. Every day of his prison life, he was counted, over and over, just like attendees at institutional churches. He looks up and carves the legend, “Brooks was here” over the beam from which he hangs his noose and soon his neck.

It’s as if Brooks desired that his presence, even in death, should be counted for something within the institution. Many fundamentalist Christians are no different; at the end of their lives, rather than a legacy of people they have loved and discipled, they will be known for their commitment to faithful church attendance.

Warden Norton

Before physical inspection and delousing, prisoners of Shawshank are lined up military style in a long row and greeted by Warden Norton. The only spoken rule inmates are given is to not blaspheme the name of the Lord.

Warden Norton himself is meticulously groomed and wears perfectly tailored suits which contrast sharply against the ratty attire of the incarcerated. He has a gold cross pinned to his lapel, and after one of the inmates is sadistically beat for asking when they could eat, Norton smiles and says he believes in two things: “Discipline, and the Bible.” Prisoners receive both at Shawshank.

Throughout the film, the warden, like many fundamentalists, treats the Bible like a magical talisman, almost as if devotion to words printed on a page could be a preferable substitution to a real relationship with God.

As Norton gives Andy more and more responsibilities, at first as prison librarian, and eventually as a creative bookkeeper, he allows small infractions such as Andy playing Mozart over the prison PA to be punished but not effect his usage of Andy for larger purposes “befitting a man of his education.”

The guards used Andy as well, asking him to do their taxes, as a way to make their lives easier and more profitable. Many Evangelical Fundamentalists have similar transactional connections with Jesus, as if the purpose of his presence is to grant prayer requests on demand rather than have a real relationship with people he died to save.

Warden Norton sees an opportunity to use free labor and profit out of introducing his institutionalized populace into society. Appropriately titled “Inside Out,” his contrived efforts were really just a façade to launder money and mask his own corruption. In this way, his efforts are not altogether unlike some superficial evangelical church programs lauded for making a difference in the community that actually function to funnel money back into the institution, and sometimes even line the pockets of church leaders.

The character of Warden Norton parallels corrupt church leaders today—which makes perfect sense, because many of them envision Jesus not altogether different than Warden Norton saw Andy: probably as an employee, and definitely as a meal ticket.

For church leaders who dress on Easter morning in clothes that others in their community are unable to afford and drive luxury cars filled with gas paid for by tithes and offerings to large, well-furnished church campuses in view of homeless and hungry people, Jesus does the heavy lifting while they sing songs and take communion.

People like you and me should take note.

Jesus fed the hungry, and lived in solidarity with the poor, the immigrant, and those rejected by society, while so many of us today eat jellybeans as our kids hunt plastic eggs.

Red

But we don’t have to live out the rest of our lives like Brooks, the guards, or Warden Norton.

Red was also victimized by the institution, and for decades said the same things that ultimately did not convince the parole board he was rehabilitated: “I can honestly say I’m a changed man. No danger to society here. God’s honest truth.”

Going to prison doesn’t redeem you, and it didn’t rehabilitate Red. Going to church doesn’t redeem people either.

Andy gave Red a harmonica, and spoke of the power of music, how it was one of the things that his keepers had not stolen from him. “There are places in the world not made out of stone,” said Andy. “There is something inside that they cannot get to, that they cannot touch…Hope.”

Red thought hope was a dangerous thing. But Andy’s escape gave Red hope, first in the form of a blank postcard sent from Fort Hancock, Texas.

Unlike Brooks, when Red left the institution, he saw that his life couldn’t be mapped out in terms that the parole board dictated: where he was supposed to work, where and how he lived. It was as if the institution was still trying to tell him when and where to even use the bathroom on the outside.

But Red followed another path, one Andy had told him of. The score swells and becomes achingly beautiful as Red hitches a ride in an old Ford truck and finds the hill and the rock fence Andy had earlier described. It is no mistake we hear a harmonica buzzing too.

Red learned to not fear the institution, and accept in faith Andy’s example of hope. It was a life he had never lived before: it was true redemption.

You and I

The life we have been offered in Christ because of his resurrection is a life of faith and hope, not rules and fear. There are no walls, no bars or guards to a life of redemption, and the more we make the body of Christ about such things, we ourselves become no different than a prison guard, and these beautiful sanctuaries we build do nothing but incarcerate those who are too weak to leave.

Today is Resurrection Sunday, a promise fulfilled by hope and love. May your days be filled with dreams, hopes, and plans rather than rules, meetings, and programs. The life we have been given doesn’t belong in an institution, but together, united in love and hope.

★★★★½