Michaelangelo, “Creation of Adam”

At the New York Times, Rabbi Mark Sameth asks pertly: “Is God Transgender?”

Here’s the short answer: No. God has neither sex nor gender. The former is a biological construct, created by God; and the latter is a linguistic construct, created by man. (See what I did there?) God, being transcendent, is outside both. You can’t gender God.

But Sameth attempts to do just that, which is why a longer answer is required here. After some introductory paragraphs involving a cousin who had sex-reassignment surgery, he turns to a few biblical texts in order to posit the existence of an “elastic view of gender” in the Hebrew Bible.

I’m a rabbi, and so I’m particularly saddened whenever religious arguments are brought in to defend social prejudices—as they often are in the discussion about transgender rights. In fact, the Hebrew Bible, when read in its original language, offers a highly elastic view of gender. And I do mean highly elastic: In Gen. 3:12, Eve is referred to as “he.” In Gen. 9:21, after the flood, Noah repairs to “her” tent. Gen. 24:16 refers to Rebecca as a “young man.” And Gen. 1:27 refers to Adam as “them.”

(I’m a bit confused, as an aside, by Sameth’s appeal to “transgender rights.” That’s a separate question from the gender of God or the concept of gender fluidity, which his article is ostensibly about. What does Sameth mean by “transgender rights,” and how is it relevant here? Maybe I’m being picky.)

That aside, in one sense Sameth is right. The Hebrew Bible does “offer a highly elastic view of gender”—if the word is understood properly, as a reference to grammar. But that is not how Sameth uses the word. He uses it to mean either one’s biological sex or a psychological construct about one’s sexual identity. And that’s where his argument breaks down.

Take, for example, his claim about Gen. 3:12, in which the author presumably refers to Eve as “he.” The Hebrew, transliterated, reads: “hā’ēs min-lî nātenāh hî immādî nātattāh ‘ašer hā’iššāh hā’ādām wayyōmer.” (“And the man said, The woman whom thou gavest to be with me, she gave me of the tree, and I did eat.”)

Sameth’s contention that the author calls Eve “he” is based on the Hebrew pronoun “hī.” You can check out all 314 of its uses in the Old Testament here. But according to Strong’s, “hī” (also hu) could mean “he,” “she,” or “it.” It was a flexible pronoun. It is even used as a reflexive pronoun (e.g., Lev. 6:9) or relative pronoun (e.g., Num. 5:18).

So yes, gender is elastic in Hebrew—the Hebrew language. This is a grammatical point only, and it is improper to extrapolate from that to speculate about Hebrew views of biology, psychology, or theology.

With regard to the other verses Sameth mentions:

- I can not tell from Strong’s how “āholōh” in Gen. 9:12 (not to mention Gen. 12:8 and Gen. 35:21) is supposed to mean “her tent” as opposed to “his tent.” The initial letter is a pronoun reference, but like the earlier one, it can be used as any of several grammatical genders, depending on context. This does not tell us that “gender” (psychological sense) is fluid, only that language is fluid.

- The Hebrew word “hanna,” in Gen. 24:16 appears to always mean “young woman” or “damsel,” not “young man” as Sameth claims. (See also, among many other passages, Gen. 24:14, Gen. 24:28, Gen. 24:55, Gen. 34:3, Gen. 34:12.) At least, I can find nowhere it does mean “young man.” Where in the Hebrew Bible is there a passage where “hanna” (or a related word) is used in reference to a biological male? There isn’t one. (Cite the text, if I be wrong.)

- “Ōtām” in Gen. 1:27 does mean “them,” but the reference here not to Adam specifically but to the human species (“male and female he created them”). The reference is to Adam and Eve. (The Hebrew word “adam” means “man,” as in the human species, but it also is the proper name of Adam, the first male. It is important to distinguish.)

***

But Sameth attempts to throw other examples in front of the New York Times’ readers’ unsuspecting and uncritical eyes.

In Est. 2:7, Mordecai is pictured as nursing his niece Esther. In a similar way, in Isa. 49:23, the future kings of Israel are prophesied to be “nursing kings.”

Okay. Let’s look at these texts. Est. 2:7 tells us, “And he”—i.e., Mordecai—“brought up Hadassah, that is, Esther, his uncle’s daughter: for she had neither father nor mother, and the maid was fair and beautiful; whom Mordecai, when her father and mother were dead, took for his own daughter.”

The key word is the one translated “brought up.” The Hebrew is “ōmen.” A more striking example, which Sameth does not mention, is “hā’ōmen,” in Num. 11:12. “Have I conceived all this people? have I begotten them, that thou shouldest say unto me, Carry them in thy bosom, as a nursing father beareth the sucking child, unto the land which thou swarest unto their fathers?”

A nursing father bearing a sucking child? To be sure, this is arresting, but the real question is what to make of it. (And, just as importantly, what not to make of it).

In Numbers 11, during a particularly trying time in the journey from Egypt to the Promised Land, when the Hebrews are being once again rebellious, Moses decides to vent his frustration with God. He says to God, in so many words, “Why me? Look at how unsuited I am for this.” The “nursing father” who “beareth the sucking child” helps to underscore, by way of analogy, how inappropriate Moses thinks it is to put such a burden on him. Have I conceived this people? Moses asks. Am I a nursing father? In context, this image is right precisely because it is wrong.

In a related way, the word reappears in Esther when the author says that Hadassah, lacking both her parents, has to be raised by Mordecai. It is not there because the author means us to suppose that Mordecai has breasts, but because in a symbolic way he provides Hadassah with what she lacks in the absence of a mother. He nurses her, not by giving her suck, but by caring for her and raising her into a woman.

To use this passage as though sheds any light at all on our contemporary notion of what it means to be “transgender” is a wild abuse of the text.

Isa. 49:23, which Sameth also cites, reads: “And kings shall be thy nursing fathers, and their queens thy nursing mothers.” That too is a striking image, but again it is important not to read too much into it. By no means should we suppose that Isaiah is prophesying that the future kings of Israel will have breasts, or that even the queens will literally suckle the Israelites. The word “nurse” is not literal; it is analogy, it is metaphor. Sameth disregards the author’s rhetorical figure in order to force Isaiah’s prophecy to fit his notion of “gender fluidity.” In this way too he abuses the text.

***

At this point, Sameth tells us what he thinks we should make of it all.

Why would the Bible do this? These aren’t typos. In the ancient world, well-expressed gender fluidity was the mark of a civilized person. Such a person was considered more “godlike.”

Well, “gender fluidity” is a misnomer here, if all he means is that sexual stereotypes and “gender roles” weren’t such as they are in Western culture. There’s no reason for us to expect that they would be. It was a different age and culture. And God, being neither male nor female, would incorporate the stereotypical “characteristics” of both. That does not mean God is “transgender” or “gender fluid.” He is, rather, transcendent of all categories.)

Sameth continues.

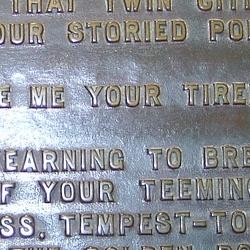

In Ancient Mesopotamia and Egypt, the gods were thought of as gender-fluid, and human beings were considered reflections of the gods. The Israelite ideal of the “nursing king” seems to have been based on a real person: a woman by the name of Hatshepsut who, after the death of her husband, Thutmose II, donned a false beard and ascended the throne to become one of Egypt’s greatest pharaohs.

Well, that’s a … stretch. What evidence does Sameth have that Isaiah borrowed from this historical example? If he has any, he does not mention it.

Rabbi Sameth: It’s a metaphor. It’s a figure of speech. That’s all. Let’s stop there. Isaiah wasn’t prophesying that Israel’s future kings would be women dressed up as men. And as for Hatshepsut, that example tells us a lot more about patriarchy in ancient Egypt than it does about “gender” in the current, hijacked usage of the word.

Sameth has more.

The Israelites took the transgender trope from their surrounding cultures [There was no “transgender trope,” to judge by the highly cursory and questionable evidence Sameth provides.] and wove it into their own sacred scripture. The four-Hebrew-letter name of God, which scholars refer to as the Tetragrammaton, YHWH, was probably not pronounced “Jehovah” or “Yahweh,” as some have guessed. The Israelite priests would have read the letters in reverse as Hu/Hi — in other words, the hidden name of God was Hebrew for “He/She.” Counter to everything we grew up believing, the God of Israel — the God of the three monotheistic, Abrahamic religions to which fully half the people on the planet today belong — was understood by its earliest worshipers to be a dual-gendered deity.

Not dual-gendered, Rabbi Sameth: non-gendered. God is not both male and female; he is neither male nor female. Pronouns, of course, do have gender—for gender, properly, is a grammatical construct—but it behooves us to not get excited and jiggly and read our agendas into the fact that some pronoun needs to be applied to God. That a pronoun has gender should not lead us to suspect that God has a gender, or multiple genders, or is transgendered, or is gender fluid, or whatever else your agenda compels you to want to say about God. God is transcendent.

But Sameth, in his haste to urge a particular ideology of “gender” upon us, misrepresents both the nature of God as well as the nature of human language.