Recently a meme made its way around Facebook; and on the left side, it depicted a member of the U.S. military; and on the right, a Mexican attempting to scale a wall. The meme told us that the soldier deserves free health care and the Mexican does not. He’s breaking a law, don’t you know? What disturbed me most—perhaps it ought not have–was, the reason I came across this meme in the first place was because a well-known Catholic apologist shared it.

The narrative we’re supposed to accept here is that health care is a reward for having contributed to society in a way that society approves of. If you’ve not—if you’re just a Mexican scaling a wall to mooch, for that’s what they do—you can go die.

This narrative is one that Pope Francis (otherwise defended by the Catholic apologist I won’t name) has warned against. Back in 2016, the pope said: “Health is not a consumer good but a universal right, so access to health services cannot be a privilege.” The pope rejected the notion that health care is for “those [who] can afford it.” (Don’t make here the facile distinction between health care and health coverage.)

In saying this, the pope is not going off on his own Catholic leftist, SJW, liberal boilerplate, Patheos blogger path. He is repeating what any one of you can read in the Church’s Magisterial texts.

But Alt! What does it mean to say that health care is a universal human right?

Glad you asked. The Compendium of the Social Doctrine of the Church tells us in §388:

The rights and duties of the person contain a concise summary of the principal moral and juridical requirements that must preside over the construction of the political community. These requirements constitute an objective norm on which positive law is based and which cannot be ignored by the political community, because both in existential being and in final purpose the human person precedes the political community. Positive law must guarantee that fundamental human needs are met.

Because “the human person precedes the political community,” he has human rights (which come from God) that the State must guarantee. Whether he is a member of that community is irrelevant because he has those rights as a person made in the image of God, and not as an American, or a Jordanian, or a Norwegian.

But Alt! Where does the Church list health care as one of those rights?

Glad you asked. It does so in the same Compendium §166:

The demands of the common good … [require] the provision of essential services to all, some of which are at the same time human rights: food, housing, work, education and access to culture, transportation, basic health care, the freedom of communication and expression, and the protection of religious freedom.

But Alt! The Compendium of the Social Doctrine of the Church is not doctrine!

I’m not trying to be amusing, dear reader; someone did in fact say that to me once. I think he was trying to make the point that what is in the Compendium has no more authority than the authority of the original source. Which might be true, but the original source is Pope St. John XXIII’s encyclical letter Pacem in Terris, and encyclicals rank just below apostolic constitutions as authoritative documents. Here is what J23 writes in §11:

But first We must speak of man’s rights. Man has the right to live. He has the right to bodily integrity and to the means necessary for the proper development of life, particularly food, clothing, shelter, medical care, rest, and, finally, the necessary social services.

But Alt! If you break the law, you forfeit those rights!

No. No you don’t. Not the rights that pertain to you as a human person made in the image of God. And the USCCB, teaching with the same authority as any successor of the apostles in union with Peter, makes this clear specifically with reference to “illegal immigrants.”

In the Bible, God promises that our judgment will be based on our treatment of the most vulnerable. Before God we cannot excuse inhumane treatment of certain persons by claiming that their lack of legal status deprives them of rights given by the Creator.

And one of those rights is the right to be treated when you are sick. Whether you can pay for it or not is irrelevant. Whether you have committed a crime or not is irrelevant.

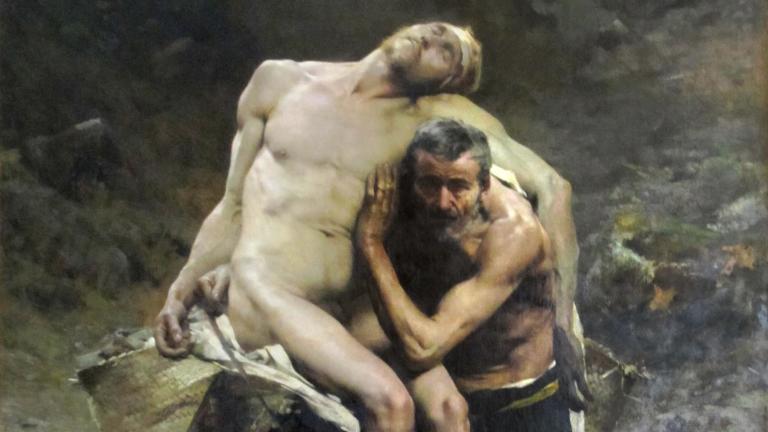

When the Good Samaritan encountered the wounded man on the road to Jericho, he did not ask if he was there legally. He did not ask whether he had committed a crime. He did not ask if he had fought in the Jewish army and did his duty. No. He paid for him to be treated, and then gave the traveler a handout on top of it.

Jesus told this parable to a legalist who asked him, “What must I do to inherit eternal life?” And then Jesus said: “Go and do likewise.”