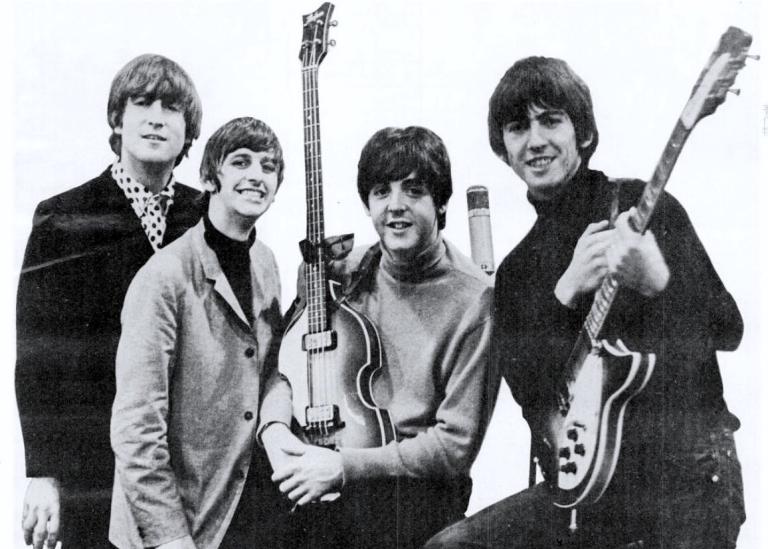

Hideous. Ugly. Grotesque. Shocking. All those things; add your own adjective. Indeed, one suspects—and one should—that the photographer, whose name was Robert Whitaker, intended that reaction. He meant for us to be disturbed by this depiction of The Beatles draped in red meat and holding the dismembered parts of baby dolls. Quick: Does The Iliad glorify war or simply expose its horrors? That is a long-debated question in the humanities, not just with respect to Homer, and everyone who approaches the arts must answer it. It also matters a great deal whether you get the answer right.

Another question that is important to get right is this one: What is this book, this poem, this painting about in the first place? What is the subject? What did the artist intend? What was Flannery O’Connor up to in “A Good Man is Hard to Find”? Or “Good Country People? Why should any decent Christian read those stories? She was just sick, sick, sick! Right? Or Slaughterhouse-Five? The title alone is just sick, and Kurt Vonnegut was a disturbed man!

Dr. Taylor Marshall recently posted this article, in which he asks the same question that may have occurred to you: “Did The Beatles Promote Abortion?” From his inclusion of the album cover above, we are meant to conclude that they did. (By the way, it is important to note that the photograph was never intended for use on an album cover, but in an altogether different context. More on that below.)

However, Dr. Marshall offers no real evidence for interpreting the cover as a commentary on abortion, other than:

(1) his characterization of the white coats as “physician smocks” (in fact, The Beatles are dressed as butchers, not physicians);

(2) his irrelevant observation that “[a]bortion was being hotly debated in the United Kingdom when this photo was taken.”

Well; case closed!

Let us stipulate two things from the start.

First, it is certainly possible—maybe even likely—that the individual Beatles were pro-choice. It would not surprise me if they were. But that is not the issue here. The issue is whether the album cover reflects a pro-choice ethos, for that is Dr. Marshall’s claim: The album cover is sick because the album cover is joyfully pro-abortion!

Second, whether or not abortion was “hotly debated” at the time is irrelevant. When Dr. Marshall points that out, he is implying that the cover must necessarily be a commentary on abortion, because abortion was being debated at the time. That is the fallacy of concurrence: x occurs at the same time as y, therefore the one must be a response to the other.

But I have searched, and I can find no one (other than Dr. Marshall) who suggests that the cover has anything at all to do with abortion. Not one. Unless there are some fairly obscure references out there (but he does not cite any such source), Dr. Marshall is the first and only in fifty years. If the cover were intended to “promote abortion,” how is it that that escaped discussion back in 1966? The Beatles, and their lackeys in the press, certainly did an excellent job keeping quiet about it. The Beatles must have been very bad at publicity. Shh. I am going to promote abortion, but don’t tell anyone about it. You are not to discuss this. If anyone asks you who John Lennon is, you don’t know.

Even if we assume the cover is a commentary on abortion, how do we know it is not pro-life? Could it have been that the band members wished to suggest the outright evil of abortion? Could they have meant to imply that abortionists are sadistic and gleeful at the the horrors they perpetrate? The Beatles are portraying abortionists, not advocating what they do. For after all, if The Beatles are depicting the remains of an abortion, is that not the kind of thing that a pro-choice advocate would wish to keep hidden? Why depict it so openly unless your intent is to make people recoil at abortion?

Dr. Marshall does not answer these questions, nor does he ask them.

I.

COVER STORIES

The most common misinterpretation of the cover—so popular that Snopes refuted it—is that it was meant to be a protest, by The Beatles, against the “butchering” of their albums by Capitol Records in the United States. (Capitol Records was known to shortchange the U.S. versions by a few tracks.)

Still another myth exists, which claims that the cover was meant to be a commentary on Vietnam. The misinterpretation of an offhand remark by John Lennon seems to lie behind this idea. Soon after Capitol Records recalled advance copies of the album, The Beatles gave an interview (quoted here) for an article in the British weekly Melody Maker.

The Beatles thought that the furor in America over their LP cover was “a bit soft,” to quote Paul.

“We were asked to do the picture with some meat and a broken doll,” said Paul. “It was just a picture. It didn’t mean anything. All this means is that we’re being a bit more careful about the sort of picture we do. I liked it myself.”

John Lennon gave a grin and roared: “Anyway, it’s as relevant as Vietnam!”

That last statement is typical Lennon sarcasm: He meant that the controversy over the album cover was much ado about nothing, but phrased it in a way that simultaneously critiqued people’s complacent attitude about the Vietnam War. Lennon’s feeling was that it was hypocritical for people to assume a pitch of outrage over an album cover featuring dolls, but to remain blithe and accepting of actual dead babies in Vietnam.

In fact, the photo was never intended for use as an album cover. At the time it was taken, The Beatles had only one-third of a finished album on hand and were not thinking about covers yet. Whatever the reason, Capitol Records (not the Beatles themselves) decided to use the “butcher photo” for the release of Yesterday and Today. The album and its cover were hastily changed after negative reaction to advance, promotional copies in the United States. This photo, also taken by Robert Whitaker, was used in its place. (It was even pasted over copies of the jacket that had already been printed.)

In a letter to reviewers, Ron Teppen of Capitol Records explained why the butcher cover was being recalled.

The original cover, created in England, was intended as “pop art” satire. However, a sampling of public opinion in the United States indicates that the cover design is subject to misinterpretation. For this reason, and to avoid any possible controversy or undeserved harm to The Beatles’ image and reputation, Capitol has chosen to withdraw the LP.

The Beatles “subject to misinterpretation”? Not the Liverpool Beatles! Who could have predicted that?

II.

A STORY OF COVERS

In his book The Unseen Beatles, Robert Whitaker explains the purpose behind the “butcher” photo. (See this article for a summary of the relevant content of the book.) The idea (which was Whitaker’s, not The Beatles’) was for a series of surreal and conceptual images that would parody the public’s “mass adulation” of The Beatles.

“I had toured quite a lot of world with them by then,” says Whitaker, “and I was continually amused by the public adulation of four people.” He planned a triptych of photographs—meant to form a sort of religious icon—that would contrast the public’s worshipful attitude toward The Beatles with their human reality.

In one photo from the series, George Harrison poses as though hammering nails into John Lennon’s head. The idea here, according to Whitaker, was to show that John Lennon—far from the invincible, etherel god he seemed to be to many—was in fact a flesh-and-blood human being capable of being hurt or pierced. (There isn’t so much the depiction of John Lennon as a Christ figure going on here, as there is a spoof of it.) The expression on Harrison’s face could be read: See, John Lennon, human being. If I nail him, does he not bleed?

In a third photo, Ringo is pictured inside a cardboard box labeled with the number 2,000,000. According to Whitaker, the point of this photo was that Ringo was no more important than any of two million other human beings. (Whitaker underestimated the population of the earth by a tad.) “The idolization of fans,” he writes, “reminded me of the story of the worship of the golden calf.”

The triptych was never completed. The “butcher” photograph was intended to include a gold background and halos over the Beatles. As a contrast with that depiction of the public’s perception of a godlike group of four, Whitaker wanted to include the most shocking image he could think of; he thought of broken dolls and pieces of butcher meat. He wanted to deconstruct the popular perception of The Beatles by showing them in the most unflattering pose he could imagine.

Indeed, one could view the series of photos as a fairly orthodox—if stylistically excessive—critique of the adulation of pop stars (a critique with which I imagine Dr. Marshall would agree): We make them out to be gods, when they are like us. The tryptich was intended to be nothing other than a spoof of the over-the-top near-worship of The Beatles. It is hard to know what the series of photos would have looked like had Whitaker carried his concept through to completion. No one can fairly judge, or interpret, work that is incomplete; who knows what may, or may not, have become of The Mystery of Edwin Drood or The Original of Laura?

In this case, all we have to go on is three photographs and what the photographer says he intended to do with them. No reason exists to dispute what he has said, or to posit a different and more ugly interpretation.

III.

EXPERT TEXTPERT OR ELEMENTARY PENGUIN?

Dr. Marshall’s article is a perfect example of how Catholics must not talk about artistic creations. It is perfectly valid to discuss secular art from a Catholic point of view; Catholics with training in the arts (I have an M.A. in literature) ought to do that. But some effort should be made to understand what the artist was trying to do in the first place. It is irresponsible to make assumptions like Dr. Marshall does, just because it just seems that way to you and your agenda is to expose all that wicked filth out there. To make false assumptions based on nothing other than initial gut reaction that something is “gross” or “kinda weird” (Dr. Marshall’s words), does nothing to promote a Catholic understanding of or contribution to the arts. In fact, it hurts it.

A case could be made that the shocking nature of the photos outpace any good or innocent intention Whitaker may have had. You might say that that is a problem of gallows humor in general, and that Kurt Vonnegut should have minded what he was about when he wrote Slaughterhouse-Five. You might say that dark satire and parody are really too risky to pull off, and Flannery O’Connor should have just busied herself with the peacocks. I would not agree with you, but at least you would show an understanding of and sensitivity toward what the artist was trying to do.

If a stereotype exists that religious or conservative critics of secular art don’t understand it, the best way to combat it is to show that we do, in fact, understand it. Embarrassing ignorance of the kind displayed by Dr. Marshall only reinforces the stereotype.

What does it mean, for example, that Dr. Marshall gives a list of everyone who’s on the Sgt. Pepper cover, together with liner notes like the following: “Lewis Carroll (author, alleged pedaphile [sic])”? Does he really mean to suggest that Lewis Carroll was included on the cover because The Beatles were into pedophilia? (By the way, the common notion that Lewis Carroll was a pedophile is and has always been an unsubstantiated myth based on his photos of young girls, which need to be understood in the context of the time and place in which Carroll lived—not based on our own sensibilities.)

Quite simply, John Lennon admired Lewis Carroll, as he admired Dylan Thomas, because he was a fan of wordplay. Read any of John Lennon’s lyrics and the wordplay is hard to miss. Although it is certainly true that The Beatles used LSD, “Lucy in the Sky With Diamonds” is better understood in the context of Lennon’s love of wordplay and unusual imagery. The imagery in “Lucy” comes largely from Alice in Wonderland, not from drugs.

Lewis Carroll is on the cover of “Sgt. Pepper” because Lennon admired his writing, and for no other reason. Dr. Marshall has no basis for his irresponsible insinuation otherwise.

One does not have to pretend The Beatles’ music is Christian, or argue for its inclusion in the Mass. Neither does one have to pretend that The Beatles were wonderful human beings. No one has to like their music. No one should have to pretend that “Imagine” is anything more than juvenile, atheist stupidity. But it is critically irresponsible, and counterproductive, to insinuate darkness or “intellectual poison” where none exists. That makes it harder to point out true poison with any credibility. Catholics who love and discuss the arts should do better—at the least, show an understanding of what the artist is really up to.

Also be sure to check out my follow-up post Seven Reasons to Reject Catholic Fundamentalism About the Arts.

The great Simcha Fisher at Patheos also takes on Dr. Marshall here.

***

If you like the content on this blog, your generous gift to the author helps to keep it active. I remember all my supporters in my Mass intentions each week.