The posts in this column contemplate our diagonal connection to God. I have written here, I mean, about the way that our life in time slopes upward into the eternal life of God. Is that too optimistic? Can these contemplations bear the weight of suffering? Should we even try to offer a meaning of suffering? Let’s take a moment to consider how the diagonal way might also be the way of the cross.

Why Do We Talk about Suffering?

There’s an irony to our worst pains: they defy description, and yet we can’t stop talking about them. Whether we deal with pain by calling a friend or writing a country song, humans seem driven to put the unspeakable into words.

“There’s a grief that can’t be spoken,” Marius sings in Les Miserables. And yet he keeps singing it: he speaks the unspeakable into song. The chorus of a classic tragedy sings long refrains about how the pain on stage resists language.

A recent issue of the journal Modern Theology took up this question. The issue featured a debate between Rowan Williams and David Bentley Hart, two of the greatest living theologians by any estimation. Williams had just written a book, The Tragic Imagination, and Hart challenged it, in the spirit of good, friendly, constructive banter. Hart took offense in particular at the William’s insistence that even tragedy never quite finds the end of language. Hart thinks that some suffering defies the impulse to speak. Williams argued back that a theologically informed imagination can’t give up on the hope that all suffering could one day make its way into words. Williams, by my estimation, got the better of the argument. If you’re keeping score.

Is Suffering the End of Meaning?

Suffering is like—feels like—the world attempting to escape meaning. It makes us aware that everything doesn’t actually happen for a reason, at least not in the sense that we tend to use that banal proverb. Some things defy reason. The death of a child or young person. A betrayal by a trusted friend or spouse. A hurricane that brings an island to its knees.

Still, the hope that all of this will eventually be “wordable” is consistent with the Christian insistence that “all things were made through Logos,” God’s original and originating Word. All things are likewise redeemed through this same Word: that’s the whole gospel right there. If a thing were utterly and conclusively unspeakable, then it would be utterly unredeemable. And Christians are charged with hoping nothing is like that.

So we speak. We don’t try to speak the ultimate and divine Logos itself, but rather our limited human-sized moments of meaning. We speak what the Greek theologians call our “little logoi.” Tiny words.

How Do We Make Meaning of the Cross?

Not that it’s easy. At the center of the Christian redemption story is the cross, and Dr. King noted that it is “difficult to see the love of God in such a shameful tragedy.” He could have said “meaning” just as easily where he said love. Difficult, but the preacher keeps preaching. The late James Cone connected King’s observation with the lament of Emmett Till’s mother over the death of her son. “Lord, you gave your Son to remedy a condition, but who knows but what the death of my only son might bring an end to lynching.” There was no meaning to the lynching. And yet she is prepared to try making some, just as Saint Paul and Dr. King attempted to make difficult meaning of the cross.

Nicholas of Cusa (d. 1464) called this halting attempt to put the unspeakable into words “conjecture.” “Every human affirmation about what is true is a conjecture.” (1.2) That’s always the case because our lives share in the great and changeless truth—Logos, meaningfulness—without being equal to it. For Nicholas that means whether the object or moment we encounter brings us joy or sorrow, we are never fully encountering its truth. To name the meaning of this birth, this death, this peaceful moment, requires a risky and creative use of language. It requires a conjecture.

These conjectures may use metaphor: perhaps the Friday of Jesus’ death was like the Day of Atonement, Saint Paul says. Perhaps my son’s suffering could be vicarious like your Son’s was, Emmett’s mother prays. Or, when we’re utterly at a loss, we may simply conjecture out loud on the event’s unspeakability, like Marius and the chorus of Oedipus Rex.

The Cross and the Diagonal Way

The diagonal way is our human attempt to share in divine meaning. This attempt is at its most challenging in the midst of overwhelming tragedy.

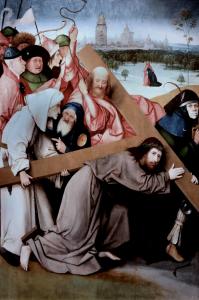

But the diagonal way is also the way of the cross. Not so much the cross planted in the ground, but angled over shoulders, first of Jesus then of Simon. On the road up the hill. From that angle, its beams are neither pointing directly up at the heavens or down at the ground. Instead they trace a line from the steps just in front of their bearer, and another from the steps just behind, toward a hazy horizon on either side. There is no transcendent sky that is not also linked with the dust of the road. But neither is there any patch of road that is not also touched by a ray of heavenly light.

On those diagonals of the cross, we conjecture on divine meaning. It’s never clear. It has no direct path to the heavenly Logos. It’s like Mrs. Till Bradley’s halting attempt to understand her loss. But she will try. She will use the language of the dusty path up the tragic hill to say what can’t possibly be said. A Christian can do no less. Because only what is taken up by Word can be healed.

So we pray our pain Godward, toward what we hope is a final, meaningful horizon.