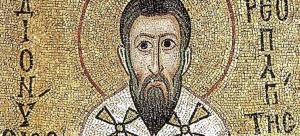

The most mysterious of all the church fathers is a man whose identity we only know by the pen name he used.

In fact, when modern historians discovered that the author who calls himself Dionysius was not in fact the man mentioned in Acts 17, they began calling him “false-” or Pseudo-, Dionysius. That’s not quite fair, holding ancient writers accountable to modern intellectual property laws. In fact, I think this annoyance missed the point. So I prefer just to call him Dionysius, or Denys, as the French say. Because it’s shorter.

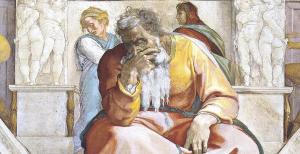

Paul’s Sermon at the Areopagus

The Dionysius from Acts is a convert from Athens, a man who hears Paul preach his sermon at Mars Hills. Mars Hills is Ares Hill, Areios Pagos in Greek, and so the hill and the Athenian council that met there was the Areopagus. Luke, then, is naming a prominent convert. Among the believers is Dionysius the Areopagite, Supreme Court Justice of ancient Athens.

The content of Paul’s sermon matters for our mysterious church father. Finding a shrine to “the Unknown God,” Paul proclaims this to be the ultimate name of the Creator. The God beyond shrines, temples, and even names made by humans.

Read carefully: Paul is not saying, God is unknown to you Athenians, but not to me. He is saying, rather, The God I proclaim is beyond all knowing. This is the paradox at the heart of all Christian preaching. What we put into words still remains beyond all human language. It’s also the paradox at the heart of the Corpus Areopagaticum—that’s the fancy Latin way of referring to the works of the later church father.

None of those Things

Our Denys was not a first century Athenian counselor. He was likely a late fifth or early sixth century Syrian. The most important thing about the name he took is not that it wasn’t really his, but the theological moment for which he selected it.

The proclaimed God of creation and resurrection remains the Unknown God. Look around you, Denys says. Every single thing you can see issues from the one who is not a single thing at all, but the source of all that is. “He is not a facet of being, rather being is a facet of him.” (God is the original Chuck Norris, I think Denys is saying.) That means that everything that is good and true of anything at all is something you can say of God. Yet God “is none of those things.”

This divine excess could check our theology before we get started. It’s foolish, even dangerous, to say anything at all about God. Why would we ever try?

Denys’s answer is that God invites us to. The Unknown God reaches for us and invites us to reach back. The place where that embrace occurs, Denys says, is called “worship.”

God’s Reach

The first bit of evidence we have of God’s invitation to name God in worship is the existence of holy scripture. All of scripture is centrally “about” the naming of God, and so invites us to contemplate God through written words. Without these revealed names, our language would be utterly bankrupt. “Let us therefore look as far upward as the light of scripture will allow” as we attempt to know the God beyond being.

For Denys, though, pouring over the names of God—light, love, beauty, truth—is only the threshold. Knowing the Unknown God is a contemplation that ends in sacramental worship. All the words that we read and sing and pray in liturgy become “a poetic narrative of all divine things.” This story we sing is our way of bringing our fragmented lives into a living, communal unity with God. In placing our bodies in that narrative, we become one with ourselves, one with one another, and one with God.

As we make this liturgical journey together, even the angels are present with us. They do not, for Denys, intervene at various mystical moments, so much as provide a heavenly scaffolding for our whole earthly adventure. Baptisms and Eucharists, Denys tells us, are embodied manifestations of the invisible liturgies of heaven. When we find our place in that poetic narrative, we walk with celestial beings who are also making their approach to the creator beyond all things.

Divine Excess

Ultimately, together with our fellow believers and the saints and angels, we sing of the God who exceeds all our songs. That is the “point” of all praise: proclaiming divine excess.

That means there is a “darkness so far above the light!” Everything we can affirm of God—God’s goodness, God’s faithfulness—must give way to what still remains hidden. To come into the presence of God is to “know an unknowing.” It is more like saying what God is not than saying what God is.

Even the Incarnation, Denys says, is a presence that leads us to affirm God’s hiddenness. This is what the Apostles learn at the Ascension: the one they know retreats into the clouds. He was somehow neither light nor dark, but simple “beyond.”

This may sound overly mystical and paradox-laden. Fair enough. But then so is Paul’s sermon in Athens. In preaching the gospel of the risen Christ, we make known the unknown God!

The theologian who calls himself Denys of Mars Hill wants us to know that he is preaching that same God. When we encounter the resurrected Christ, we encounter the great mystery of a God who is, finally, beyond all being and nothingness. And only God’s loving reach allows us to commune with this transcendence.