Advent, the Christian liturgical season leading up to Christmas, is the time when songs and sermons about hope fill churches of all denominations. We read prophecies about the beating of swords into plowshares. We sing “Come Thou Long Expected Jesus,” with confidence that his coming will “hope to all the world impart.” Sometimes we’re even more directive in our petitions. “Give them vict’ry o’er the grave;” “death’s dark shadow put to flight.” Those are but two of the hope-bathed lines of the seasonal favorite “O Come, O Come Emmanuel.”

Strange, though, to talk about hope when the world is demonstrably getting worse. When racism has become public discourse in liberal democracies. When a president of a world power uses military force to try and recreate the sort of empire most assumed was a relic of the old world. And over all, the great threat multiplier that is the climate emergency, likely now past the tipping-point according to the United Nations. Ours are not times that inspire hopefulness.

Avoiding Hopelessness

I felt the hope/hopeless tension while watching a recent episode of HBO’s White Lotus, released, as it happens, in the second week of Advent. “The world is falling apart,” one character says, rather puzzled that she even needs to say it out loud. It’s a theme, or at least a through line, of both seasons of the show: reality is hopelessness. But money–lots of it–can at least temporarily distract us from the real.

This tension is not lost on my colleagues in the world of theology. Some are suggesting that we abandon the language of hope altogether. It’s time for Christianity to embrace hopelessness: that’s the way Miguel de la Torre, professor at the Iliff School of Theology in Denver, puts it. It’s an impulse I understand, even if ultimately I disagree.

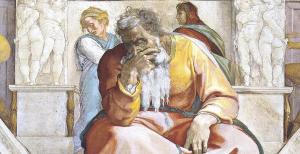

I understand the impulse because a certain kind of hope looks like the privilege of those insulated from the harshest of the world’s present realities. For White Lotus: vacationers at a Sicilian resort can be hopeful; prostitutes in a tanking economy have no such luxury. The “fat and sleek” of Jeremiah’s prophecies (eg. 5:28) can afford hope. The orphans and the hungry cannot. Communities who send their garbage far away have no motive to despair. Those who wake up every morning smelling it do.

Hope and Optimism

So a certain kind of hope can look like blind optimism, either naively or willfully acquired. Further, it keeps us from confronting with any true attentiveness the powers and principalities of this present darkness. If it’s all going to be ok, I am likely not going to change the way I eat or water my lawn. Let’s not despair. Instead, we’ll think positive thoughts.

Alternatively, some Christian theologies of the end times account for hope by giving up on creation entirely. Our hope is not in this earth at all, but in the new one that God will make after he destroys this one. But the idea that our world is not really what matters releases me from responsibility just as surely as the smiling assurance that all shall be well. Either way, hope looks like a half-interested patronizing assurance that there’s nothing to worry about, you’ll see. And this is not an attractive Christian posture. That is de la Torre’s point, and I think it’s a good one.

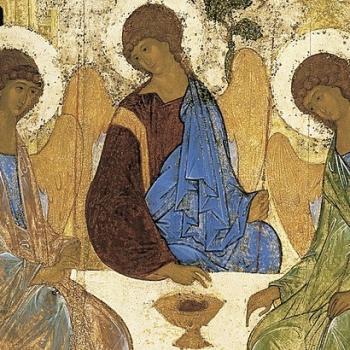

Advent is about Hope beyond Hope

Still, I am not ready to embrace hopelessness. That’s because I don’t actually think such leisurely positive thinking is what Christians have, since ancient times, meant by the word “hope.” Rather, hope is the coming–the advent–of God that none of us knows quite how to expect. Hope is precisely the arrival of the unhoped for, you might say. It’s the virtue that allows people of faith to confront the reality of looming disaster–war, famine, disease, mass extinction, loss of coastal lands–and still get out of bed the next morning. We are working alongside God, even if we have no idea what the final result will be.

This is why Jeremiah can speak of the mass destruction coming to Jerusalem, but then, in almost a different voice entirely, insist that the God of mercy will not make a full end of their lives. It’s not desolation or hope. It’s both.

Matthew’s parable of the bridesmaids–another of the Advent readings–is what hope looks like in the New Testament. Not an assurance that all will be fine, but the long and difficult habit of staying awake. Keep watch, so that you’re ready when the suprise of the groom’s arrival brings whatever unanticipated grace it brings.

I want to hang on to that sort of vigilant hope. Otherwise I’m forced to admit that hope is nothing more than the optimism of the distracted rich. And so embrace hopelessness.

It may not all turn out ok. It almost certainly won’t. And somehow that won’t count as evidence that God has forgotten us. That’s what Advent hope is all about.