There were liberal evangelicals? What if I told you that evangelical Christians were the original social justice warriors? Seems unlikely, I know, but keep reading.

One of my favorite quotes is from a British novelist named L. P. Hartley — “The past is a foreign country; they do things differently there.” History is full of surprises. It is not just a version of the present with strange clothes and bad technology. Cultures and institutions can sometimes change very rapidly in just a few generations.

Consider, for example, evangelicalism. Evangelicalism has become a major force in conservative politics in the U.S. that is especially linked to support for Donald Trump. Indeed, the number of self-identified evangelicals grew during the Trump Administration, although not necessarily the number of evangelial church-goers. This trend caused conservative commentator David French to deride “the decades-long transformation of white Evangelicalism from a mainly religious movement into a Republican political cause.”

So it might surprise you to learn that even White evangelicalism was once associated with liberalism and progressivism. This wasn’t necessarily true of all of evangelicalism, but it was certainly true of a large part.

First, some historical background. Just who are evangelicals, anyway? Term “evangelical” was coined in the 16th century by Martin Luther — in German, Evangelische, from the Greek euangelion, “good news,” referring to the Gospel. Luther taught that salvation came from faith in the Gospel’s message rather than by obeying the laws of the Church. After Luther’s time the title “evangelical” was associated with a number of transdenominational movements within Protestant Christianity.

The Second Great Awakening

Many historians will tell you the current version of evanglicalism began in 18th century Europe with a Protestant movement that emphasized a personal experience of repentance and living according to Christ’s teachings. When this movement spread to America in the 1790s, it touched off a phenomenon called the Second Great Awakening. Huge, boisterous camp meetings and revivals spread across the land, attended by people seeking catharsis in Christ. The Awakening presented a form of Christianity that was optimistic and egalitarian. It also stressed individualism, especially the need to make a personal commitment to Christ. Merely attending church and listening to sermons wasn’t enough.

Evangelicalism seemed a breath of fresh air at the time, especially in contrast to the prevailing Calvinism, which emphasized the sinfulness and depravity of humankind. The evangelicals preached that people had it in them to be better people, and Christ would show them the way. And a portion of evangelicals took Christ’s teachings about caring for those who are poor and oppressed quite seriously.

Evangelicals and Social Reform

You’ve probably been told many times that in the antebellum U.S. South, Christian ministers supported slavery, which is a black mark on Christianity. And this is true, especially of ministers who served in their positions at the pleasure of plantation owners. But evangelicals elsewhere were leaders of the abolitionist movement.

For example, Baptists in northern states began organizing in opposition to slavery in 1840. This put them at odds with southern Baptists. Rancor came to a head when the main convention began rejecting slave owners for missionary positions, saying that slave owners could not be true followers of Jesus. This caused the southern group to break off and form the Southern Baptist Convention in 1845. Evangelicals in Britain also were behind the push to end British involvement in the slave trade in 1807 and ban slavery in most of the British Empire in 1833. This was very much in keeping with the evangelical movement’s promotion of justice, mercy, and humanity as expressions of the teachings of Christ.

Yes, it can be argued that 19th century evangelicals were the original social justice warriors.

American evangelicals also were the driving force behind the celebrated temperance movement. And they took up a number of other social causes, such as criminal justice and education reforms.

The Social Gospel

After the Civil War and the ending of slavery, evangelicals and other Protestants in the U.S. formed the Social Gospel movement, which was prominent from about 1879 to 1920. Social Gospel advocates felt called to spread the Kingdom of Heaven through social improvement as well as individual salvation. They worked to end child labor, to increase wages and shorten the workweek, and to improve living conditions for the poor.

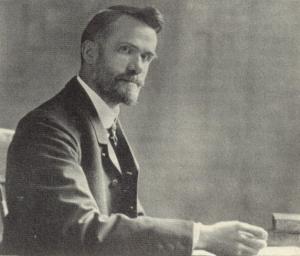

The Baptist minister Walter Rauschenbusch (1861–1918), one of the leaders of the Social Gospel, spoke for the movement when he said “The essential purpose of Christianity was to transform human society into the kingdom of God by regenerating all human relations and reconstituting them in accordance with the will of God.”

The Social Gospel gave rise to the original Progressive movement in the U.S., and many of their goals eventually would be realized through the New Deal reforms of Franklin Roosevelt.

At this point, you might be wondering how evangelicals went from the Social Gospel to Donald Trump in a mere century. Well, one, not all 19th and early 20th century evangelicals were committed to improving society. But it must also be remembered that, because of racial segregation, evangelicalism in the U.S. moved on two separate tracks — one Black, one White. The Black church more often continued to promote justice, mercy, and humanity as expressions of the teachings of Christ.

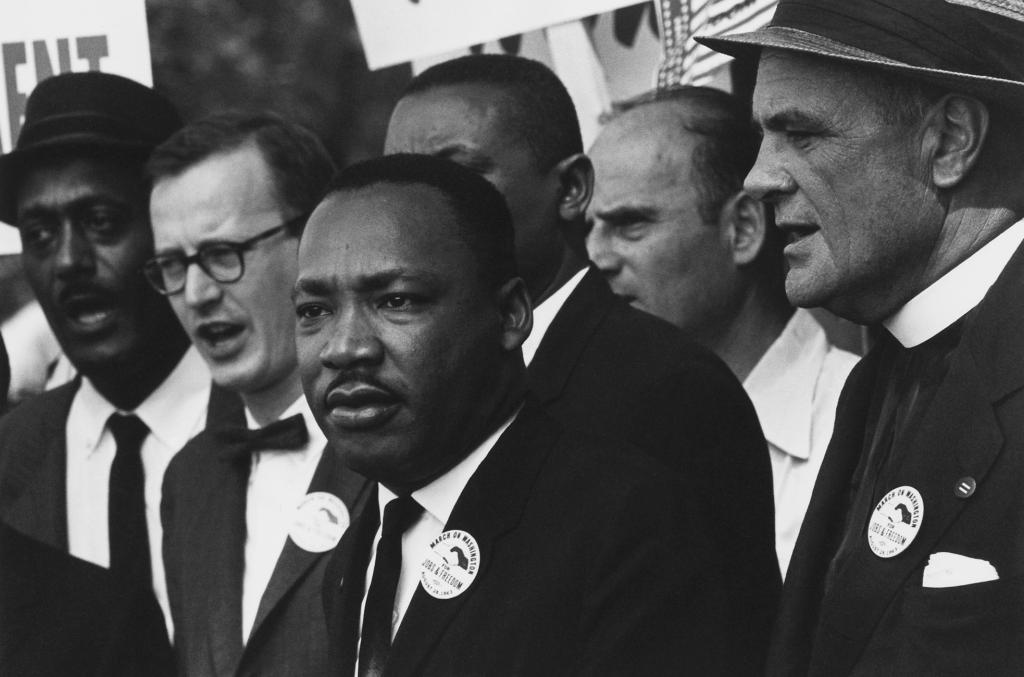

When the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King. Jr., worked for racial equality, he was drawing on evangelical tradition. Likewise, when the Rev. William Barber organized the Moral Monday movement, he was drawing on evangelical tradition.

Evangelicalism Today

It must be said there really are White liberal evangelicals in the world today, also. I have met some. They seem to be keeping their heads down at the moment. But it hasn’t been that long since President Jimmy Carter, a known liberal, could also identify as an evangelical and nobody thought much of it. In 2000 President Carter left the Southern Baptist Convention, however.

Still, the story of how so much of White evangelicalism came to be so disconnected from its roots is one that needs to be told, and I hope to explore that in another post.