There is a new Global Faith and Media Study on how news media cover religion and religious issues. Apparently neither journalists nor religious people are happy with religious journalism these days.

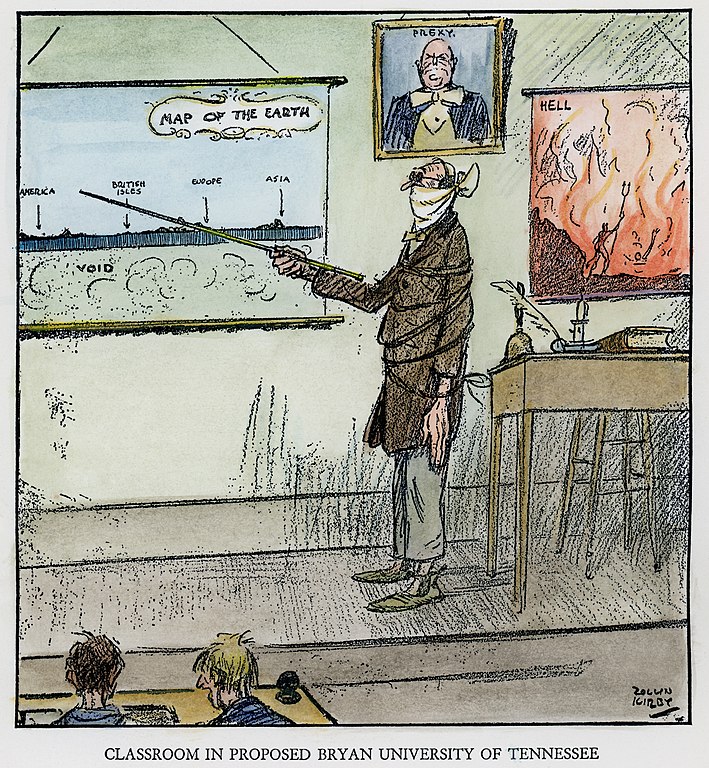

But it’s arguably been worse. Consider the s0-called Scopes Monkey Trial of 1925. You probably recall that a high school teacher in Tennessee named John Scopes was put on trial for teaching evolution, which violated Tennessee law. The trial became a media circus featuring two famous lawyers, Clarence Darrow (for the defense) and William Jennings Bryan (for the prosecution). Much of the trial testimony centered on the biblical story of the Creation.

You may not know that a Maryland newspaper, the Baltimore Sun, paid $500 for Scopes’s bail. The paper also paid part of Clarence Darrow’s legal fees and the $100 fine when Scopes was convicted. It was primarily the Sun‘s reporting that made the story a nationwide sensation. The newspaper made itself part of the story in ways that would be considered unethical today.

Reporting or Editorial?

The Sun sent its popular columnist H.L. Mencken to cover the trial. Mencken made no pretense of objectivity. He was famously opposed to organized religion. “One of the most irrational of all the conventions of modern society is the one to the effect that religious opinions should be respected,” he once said. It was Mencken who first called the proceedings the “Monkey Trial,” and the name stuck.

In Mencken’s reporting, the trial was biased against Scopes from the beginning. For example, on July 11 Mencken wrote,

The selection of a jury to try Scopes, which went on all yesterday afternoon in the atmosphere of a blast furnace, showed to what extreme lengths the salvation of the local primates has been pushed. It was obvious after a few rounds that the jury would be unanimously hot for Genesis. The most that Mr. Darrow could hope for was to sneak in a few bold enough to declare publicly that they would have to hear the evidence against Scopes before condemning him.

This may have been accurate.. However, it’s fair to say that no reporter today would refer to local citizens as “primates” in a news story.

The Ethics of Journalism

Even as Mencken was reporting from Tennessee, there was a strong move among American newspapers for professional standards and ethics for journalism. The late 19th century had been the era of “yellow journalism,” in which stories were sensationalized and facts were, um, creatively enhanced to sell newspapers. This reached a peak when exaggerated and sometimes completely fabricated “news coverage” in newspapers owned by William Randolph Hearst and Joseph Pulitzer helped push the nation into the Spanish-American War in 1898.

In 1901 two of William Randolph Hearst’s writers, Ambrose Bierce and Arthur Brisbane, separately published columns suggesting the assassination of President William McKinley would do the nation good. When McKinley was shot on September 6, 1901, and died on September 14, people accused Hearst’s writers of driving the assassin to do the deed.

Soon professional groups such as the Society for Professional Journalists, formed in 1909 as Sigma Delta Chi, began to put together guidelines for best ethical and professional practices. Journalism also became an academic subject in which getting the facts right was the first priority, followed closely by eliminating personal bias in news stories.

The View From Nowhere

In more recent decades journalism is sometimes accused of going too far to avoid being perceived as biased. Economist and New York Times columnist Paul Krugman explained why that’s a problem: “If a presidential candidate were to declare that the earth is flat, you would be sure to see a news analysis under the headline ‘Shape of the Planet: Both Sides Have a Point.'”

Writing news that treats all sides of an issue equally even when some of those sides are ridiculous is sometimes called the “view from nowhere.” This happens when reporters leave out context and background that might reveal, for example, when an interview subject is lying.

It’s probably the case today that no general interest news outlet, including the Baltimore Sun, would be so openly partisan in its coverage of a religious issue as the Sun was with the Scopes trial, if only to avoid losing readers or viewers. But that doesn’t mean faith and media are getting along any better now than they did then.

Faith and Media Today

Going back to the recent Global Faith and Media Survey, what are the current issues with reporting on religion and religious issues? One of the issues that struck me as I looked at the data was the problem of stereotyping. “Religion is frequently positioned as a conservative or extreme force in coverage and this framing drives the tendency to seek out outspoken dogmatic spokespeople over more middle-ground religious observers with mainstream views,” the study said.

I think that’s a good point. Islam is rarely in the news except in regard to violence and terrorism, for example. In the U.S., Christian Nationalism has become a huge part of the political landscape that can’t be ignored. I don’t think news coverage so far has made it clear that many Christians are opposed to Christian Nationalism.

Today news reporting is suffering from shifting business models. Few news organizations keep specialized religion reporters on staff. The general news reporters, when asked to cover stories involving religion, fear getting it wrong. It takes time to understand a religion in any depth, and covering a religion one knows little about must feel like covering news in a foreign language.

Religious Diversity Is Lost in Media

The Global Faith and Media survey also found people thought religion was too marginalized. It isn’t seen as something that attracts reader interest unless there is controversy or scandal involved. But religion permeates society and culture; it makes up the landscape of our inner lives and conditions how we make sense of reality. And this affects all of us, including the nonreligious.

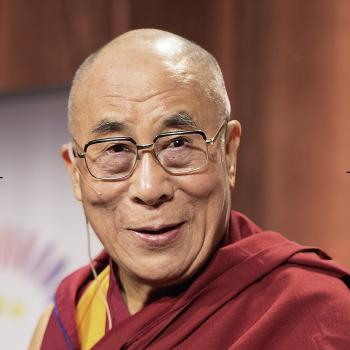

It’s also the case that religion is incredibly diverse and growing more so. Yet “religion” in mass media disproportionately focuses on the most conservative and dogmatic parts of it. If you aren’t a right-wing evangelical with political connections or a conservative Catholic, good luck getting media attention.

In 2020, Justin Ray of the Columbia Journalism Review interviewed Nick Fish, the president of American Atheists, an organization “dedicated to advancing the civil rights of atheists, promoting separation of religion from government, and providing information about atheism.” Fish complained that the perspective of atheists is entirely ignored.

He also said, “People use religion as a shorthand for morality. They will frame someone like Jerry Falwell Jr. as a faith leader, and will go to him for ‘analysis about the moral direction of America.” This was before Jerry Falwell Jr. became mired in scandal himself. But this exemplifies how’ an unrepresentative few somehow stand in for all of “religion” in news media. I remember that for a long time in the 1980s and 1990s, whenever television news wanted to present the perspective of “religion,” it would call on the same few conservative evangelicals, notably Jerry Falwell (the elder) or Pat Robertson. The perspectives of liberal Christians and not-Christian religious people were ignored.

And the Moral Is …

It’s probably the case that faith and media always will be awkward with each other. Religious organizations probably need to be more proactive about media relations. Reporters could probably use broader general knowledge about religious diversity. The Global Faith and Media Survey pointed out that “In all regions the journalists rarely represent the plurality of religious views present in society,” which

“becomes self-limiting in exploring a diverse faith agenda.”

In a 2016 interview, religion lecturer Diane Moore told the Harvard Gazette, “We can say it’s the media’s fault that we have such a one-sided understanding of Islam or other religions, but I don’t think it’s the media’s fault. The media ends up reproducing assumptions about religions that are embedded in our culture that are problematic, and they do it often unwittingly.” Let us hope for more dialogue that will open minds to better news coverage of religion.