Monastic book production in the Middle Ages began in Ireland. This is recorded in the book How the Irish Saved Civilization by Thomas Cahill. The book tells the story of how Irish Christian monks preserved much of the knowledge and literature of Greek and Roman antiquity after the fall of Rome, thereby saving civilization. The Irish monks did this by copying every manuscript they could find. They didn’t stop at Bibles. They copied Virgil’s Aeneid and the treatises of Cicero and Plato’s Republic. And more. And then they traveled eastward to Britain and the European continent to spread knowledge of book making and love of literature. From the 5th to the 13th century every book produced in Europe was hand copied by Christian monks.

Thomas Cahill died recently, which inspired me to re-read How the Irish Saved Civilization. The book was a best seller that caused quite a stir when it was first published in 1995. It received glowing reviews, although some critics griped that Cahill’s claims for the role of the Irish in saving civilization was overstated. Still, it’s a grand book that begins in 406, right before great hosts of barbarian tribes — Visigoths, Ostrogoths, Vandals, Franks, etc., who in turn were being invaded by Huns — swarmed across a frozen Rhine River in Gaul to attack the Roman legions on the other side. By about 476 the western half of the Roman Empire, including all of it in modern-day Italy, had disappeared. Rome’s fall began the Dark Ages. Thomas Cahill argued that had the Irish monks not made copies of the great books of antiquity, they might have been forever lost.

Ireland was never part of Rome’s civilization. By most accounts it was a wild and violent place. Some time late in the 4th century a 16-year-old boy of Britain named Patricius was captured by Irish raiders and sold into slavery in Ireland. After six years of hardship he escaped and returned to his family. Patricius became a priest and returned to Ireland to convert the Irish to Christianity. Today Patricius is better known as Saint Patrick (ca. 385-461; in Irish Gaelic, he is Naomh Pádraig). Patrick introduced Christian monasticism to the Irish, who took to it with much enthusiasm. Monasteries multiplied. By 600 CE the Irish were the most monasticized people in Europe.

How Medieval Christian Monks Produced Books

Monastic book production in the Middle Ages was more than just copying. The monks were involved in all aspects of book creation, including the materials. Paper had been invented in China about 150 CE, but there was no paper in Europe before the 11th century or so. Instead, monks made parchment from animal hides that were cleaned, stretched, and bleached. The best quality parchment, called vellum, was made from calves’ skin. The finished pages were sewn into leather bindings with thongs. In the later Middle Ages, large books often were bound with wooden boards covered in leather, which made them very heavy.

The monks who did the copying were called scriptores, and they worked in large rooms called scriptoriums that were filled with wooden chairs and writing tables. Usually a rule of silence was maintained during working hours. A senior monk would supervise, maintaining discipline and assigning pages to be copied. Some sources say the scriptores worked only during daylight to avoid the fire hazard of candles, but Cahill’s Irish monks left us accounts of working late into the night. And we know the scriptores did not always enjoy their work, because sometimes they left complaints in the margins.

Illuminated Books

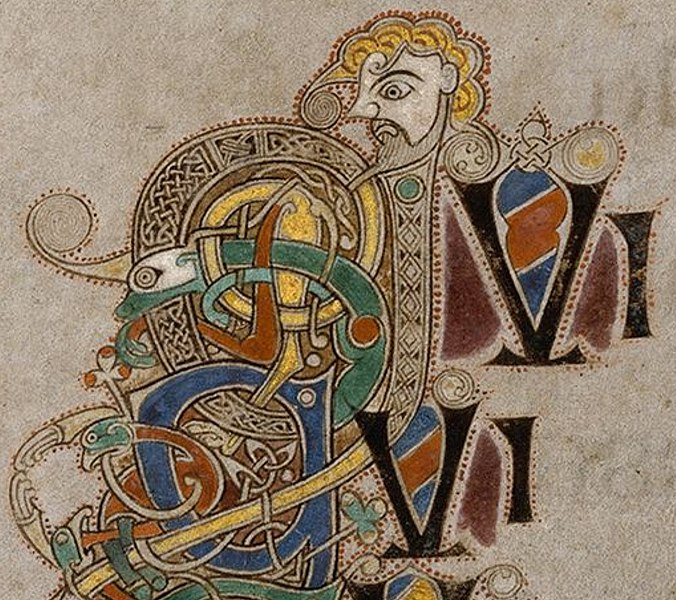

The illumination of books meant decorating them with painted illustrations and ornamentation, usually using inks mixed with silver and gold. Illumination probably began in Muslim countries with the decoration of Qurans. In Europe, the great age of illumination is said to have begun about 1100 CE, but the Celts of Britain and Ireland were producing illuminated books much earlier. One of the most celebrated illuminated books is the Book of Kells, believed to have been created about 800 CE. The Book of Kells contains the four Gospels with some other texts, in Latin. It is considered the finest example of “insular” art (from insula, “island”), a style that originated in Ireland and spread to Britain. Insular art combined traditional Celtic and Anglo-Saxon styles and motifs.

Creating an illuminated book required planning the pages in advance, determining where there would be text and where there would be illustration. The vellum pages were marked with lines for the text, leaving blanks for the art. The text was written first, usually in black ink but sometimes in gold or another color. After pages were proofread, another monk would add chapter titles and subtitles in a bright colored ink. Then the page was passed on to the illuminator, who painted the images and added the gold illumination.

Obviously, a labor-intensive illuminated book was an expensive thing. A particularly gorgeous Bible would have been the pride of any church or monastery housing it. In the later Middle Ages, illuminated prayer books, or books of hours, were much in demand by the wealthy nobility of Europe. These books probably were big money-makers for the monasteries. And this may have been why the monastic monopoly on book production ended in the 14th century, when laypeople went into the illuminated book business. But the hand-copied book industry was dealt a fatal blow in 1452, when Johannes Gutenberg used movable type and a printing press to publish a Bible.

Next: Piety and Peril: Life in Medieval Irish Monasteries