I recently moved, and this morning while unpacking a box of books I came across one I probably haven’t looked at for 50 years — The Prophet by Kahlil Gibran. When I was in college — 1969 to 1973 — this was one of the books everybody read, or claimed to have read, or at least carried around and cited occcasionally.

The Prophet was first published a century ago in 1923, and I doubt that it has ever been out of print since then. It’s a short book of prose poems that one might call brief sermons or meditations, spoken by a sage named Al Mustafa — “the chosen and the beloved, who was a dawn unto his own day.” The book has no clear sectarian orientation, although God is mentioned now and then.

And now that it’s in public domain, you can read it online. There is also an animated film version, released in 2014 or thereabouts.

Quotes from The Prophet

Here’s a sample:

When love beckons to you, follow him, / Though his ways are hard and steep. / And when his wings enfold you yield to him, / Though the sword hidden among his pinions may wound you. / And when he speaks to you believe in him, / Though his voice may shatter your dreams as the north wind lays waste the garden.

Not your standard inspirational spiritual quotes, in other words. If that speaks to you, The Prophet may be worth your time.

One quote from The Prophet I’ve carried with me through the years is “Your daily life is your temple and your religion.” Religion is a loaded word these days, and I want to address that in a future post. Most of the time people use the word to refer to a category of belief systems and the institutions that promote and support them. But in much earlier times religion was more about the way one lived and the obligations one carried out faithfully. To what do you give your time and attention? What do you do conscientiously and faithfully? In a sense that’s your true religion. And it may or may not have anything to do with beliefs or institutions.

About Kahlil Gibran

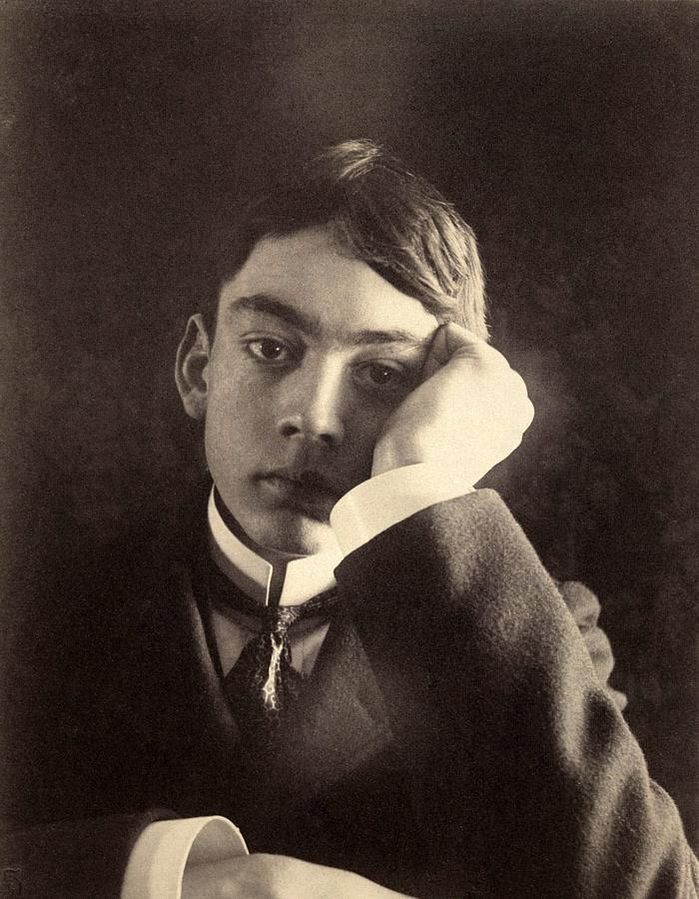

Khalil Gibran (1883-1931) was born in Lebanon into a family of Maronite Christians. He immigrated with his mother and siblings to Boston in 1895. His American teachers recognized that he was gifted at drawing and painting, and they encouraged him to study art. His artwork received enough recognition that he was able to study in Paris from 1908 to 1910. He was also writing by then. His first works were mostly short stories, in Arabic.

Gibran’s first book in English was The Madman, His Parables and Poems. It was published in the U.S. in 1918 by Alfred A. Knopf. You can read it here; it’s a book of little vignettes. This was followed by The Forerunner in 1920 and The Prophet in 1923. Several other books came after. But it was The Prophet that somehow caught on.

About The Prophet

After The Prophet was published, demand for the book doubled every year. At the time of Gibran’s death in 1931 the book had been translated into French and German and was selling briskly in Europe. It’s been translated into many other languages since. Someone bought the millionth copy of the book in 1957. And then The Prophet became something like the official catechism of the 1960s counterculture.

Professor Juan Cole, historian of the Middle East at the University of Michigan has translated several of Gibran’s works from Arabic. He spoke to the BBC about the appeal of The Prophet — “Many people turned away from the establishment of the Church to Gibran,” Professor Cole said. “He offered a dogma-free universal spiritualism as opposed to orthodox religion, and his vision of the spiritual was not moralistic. In fact, he urged people to be non-judgmental.”

But The Prophet, one of the best-selling books of all time, was never accepted into the English language academic literary canon. Gibran is considered a major figure of Arabic literature, but most western literary critics and academics have dismissed The Prophet as insipid and sentimental. The problem, some have argued, is that The Prophet is a Middle Eastern work even though it was written in English. It is more closely related to the didactic work of long-ago Persian poets like Rumi and Saadi than to anything in modern American literature.

The Next Hundred Years

Sometimes a book or a song or a work of art resonates with a particular time and place and with a particular generation. So it is hugely popular when it’s new, but it doesn’t catch on with generations that come after. Will The Prophet become a work for the ages, whether academia approves of it or not? It’s certainly got a good start.

Reading it again, I found some lines that still resonate with me and others that don’t. But this is probably an individual thing. For example, today I was very much taken with this bit:

“Your children are not your children. / They are the sons and daughters of Life’s longing for itself.”

But someone else may just find that odd.

End note: Back when I was in college everyone also was reading anything by Hermann Hesse (1877-1962) — especially Steppenwolf, Siddhartha, and The Journey to the East. I remember getting bogged down in The Glass Bead Game and not finishing it; maybe I should try it again. Also popular was something called Jonathan Livingston Seagull by Richard Bach, which I can’t say I remember clearly. There were birds. It’s been a while.