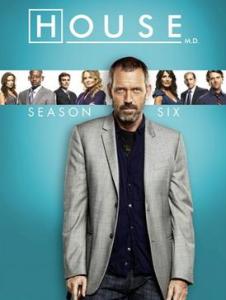

Good House Keeping: House, M.D. and Faith through Stoic Philosophy

Thousands of years of blazing insight are available to the world. It is likely that you have the power to learn anything you want at your fingertips. So today, honor the Stoic virtue of wisdom by slowing down, being deliberate, and finding the wisdom you need. – Marcus Arelius

It’s about truth. ― David Shore

Massive Attach, Teardrop (Instrumental)

There’s a need for a doctor these days

The year was 2004. I was settled into life’s groove going through the expected motions of one closely approaching their middle years. Nothing drew immediate attention, and the days dribbled one into the other. The daily schedule was predictable. Nights came to a slow close without any drama or excitement. I can recall thinking, this is it ? This is what it’s going to be like from now on? From an external view, all matters appeared to be in place. Internally, there was nothing to gleam enthusiasm. The early years of the 21st century were nothing but ordinary. Then, the phone rang. The voice on the other end said, “did you see that new show?” It was from that unassuming call that everything changed.

The following Thursday evening I took it upon myself to find out why this new show was such a must-see for me, or so I was told. Just like that, things changed. In that one-hour primetime viewing, I was hooked. House, M.D. became the interrupted escape to the zombie grind of the week.

It didn’t take long for me to start to think, isn’t (Dr. Gregory) House a stoic? Once again, the echoed effect of internal change hit like a massive seismic shift in my theoretical; mind. After watching – binging if I’m going to be honest! – all eight seasons – ending May 21, 2012 – I continued to critique the characters, plot lines, subtextual themes, philosophical bends, theological notes, and even the recurring nonverbal character of cancer. All these years later, after the end of the last season, House still holds a special pop cultural experience for many.

My own unanswered questions remain, isn’t (Dr. Gregory) House a Stoic? And, with all the theological interjections through the eight seasons, doesn’t Stoic philosophy have a historic relationship with faith and core belief systems? This is where the apologetic fun begins. Let’s see how an apologetic deconstruction of stoicism helps solidify faith and belief structures using the past decade’s number one stoic character Dr. Gregory House and his entourage.

What’s Stoicism?

To start the conversation, it’s important to examine the basics, the three pillars of Stoicism – Logic, Ethics, and Physics. These three basic philosophic pillars of Stoicism assist in how life can be flexibly structured to endure not only the stressful essentials of life but equally the unspoken yet highly sought-after stream of happiness. Stoicism is not going immediately grant a state of happiness, or euphoria when an issue has been resolved.

Stoicism necessitates daily practice and clear attention to how Logic (word, thought), Ethics (interactions, situations), and Physics (existence, nature) interact. These three pillars need to be incorporated into daily Stoic practice. The good news is that in time Stoicism can lead to a mental paradigm shift toward a more productive, stress-reduced, and clear association with the trivial and astronomical issues in our lives. Stoicism suggests that we are capable of steering clear of self-defeat as we relate to the unfolding chapters in our days. Let’s just phrase it this way, this is where the fun begins.

The three pillars of Stoicism advance into a more granular level, the four virtues – Courage, Temperance, Justice, and Wisdom.

Mechanically, the three pillars relate to the four virtues of Stoicism, Courage, Temperance, Justice, and Wisdom. These two combined fundamental levels of Stoicism demonstrate how to understand daily interactions through Stoic thought, philosophy, and posture. The combined pillars and virtues highlight a living technique that clothes a complex structure in a poetically elegant fashion.

In relationship to the four virtues of Stoicism there are the four cardinal virtues – prudence, justice, fortitude, and temperance. Further, there are three theological virtues – faith, hope, and charity. These three theological virtues would later expand to include love. Keeping on the development of the theological virtues, King Solomon narrated virtues he later in his life came to recognize – faith, courage, compassion, integrity, and justice. Contemporary philosophers and psychologists have sought to coin the six Values-in-Action (VIA) that are to be understood as universal virtues – justice, humanity, temperance, wisdom, and transcendence.

Each of these elements, albeit virtues or pillars, overlap at some point and seek to serve as tools for humanity to relate to their physical realities and contend with the complexities of the world. Wisdom and Justice remain consistent in both faith/belief systems and Stoic disciplines. Ironically, these are the points that the character House both values and discounts almost at whim.

Interesting to note that fans and other cultural critics who have applied a faith/theological/philosophical reading of House M.D. tend to lean heavily on episodes that deal directly with religious context. Following the work of Barbara Barnett in her article Faith, God, And Religion on House, M.D. (2015) I concur that there is much more to House’s acceptance, denial, questioning, and indeterminate relationship to faith/belief systems.

Atheism or bust?

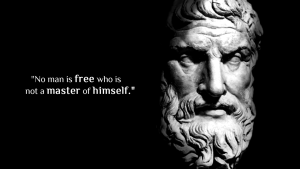

The character House states his fundamental atheist perspective echoed throughout the eight seasons of this television drama, “either God doesn’t exist or God is unimaginably cruel.” Throughout the run of the series House took pride in “mocking colleagues and patients who express any belief in religion.” Both these quotes can be drawn back to both the skeptical philosopher David Hume, and the Greek philosopher, and Stoic, Epicurus. In an odd counterpoint to himself, House further qualifies his atheism stating that he doesn’t believe in an afterlife…he finds it better to believe that life ‘isn’t just a test.’ Given this final quote, that life “isn’t just a test,” underscores that there is some level of faith and belief system that House recognizes yet is unwilling to openly admit.

Barbara Barnett takes a deep dive into the major episodes in all eight seasons and how faith and religion are noted. My argument is that the subtext to House’s ongoing tug-of-war with faith/belief system need not be limited to any prescription of virtues nor the pillars of Stoicism. House fluctuates between his acceptance of faith/belief systems internally with his external atheist doubts.

My argument sheds a different light on the depth of the character Gregory House, M.D. I propose that the self-proclaimed atheist is one who seeks to have a firm faith/belief system. Again, other pop cultural fans have even ranked the top episodes of House, M.D. that deal with religion. It’s the discourse and covert desire to embrace faith/belief system that I argue is central to the identity of House. Just looking at the episodes that directly point to religion or faith is too trite a low-hanging fruit venture. My apologetic deconstructive reading of House sets in motion the opportunity for us to see how the classic, theological, and philosophical virtues/pillars function within our daily lives. It’s this self-analytical apologetic deconstructive reading that turns the microscopic lens on our realities. Is a poetic tragedy worth taking? An adventure into a faith/belief system for the fortification of faith/belief structures? A rhetorical answer to these is the overarching “yes.”

Not so private

In season 6, episode 15, Private Lives, House is accused of reading sermons at a time when he must contend with the passing of his father. On the surface, the baseline is that House is reading to discover something about his biological father. House is seeking to relate to his familial lineage that he has, up to now, discounted. I argue that the subtext to this action – reading of sermons – is House’s veiled attempt at questioning his own faith/belief system. In his own way, House is mourning for a relationship he can no longer biologically ascertain. There is another level to this search. I propose that House is mourning for and at the same time seeking another father (read: a spiritual Father). House segues his physical mourning for an instinctive spiritual searching. House is seeking to replace the physical father with faith/belief in a greater Father. In his own way, House is building from the ground up, his faith in a belief system.

At that critical moment, at the close of the episode, when House states, “…my father died…” For something to die away is simultaneously the opening of a new life. In this simple comment, House transcribes the passing of his biological father for a faithful desire to die from his atheist history. His emotional movement is not for the one who passed but is underscored by the loss of the one he never had, internally, his spiritual Father. House mourns for his own passing. House is seeking to transcend from a position of nonbelief into one of faith in a secure belief system. At that moment, House’s scientific mind, his Stoicism is transposed by a longing for faith and the comfort of a belief system.

Another critical moment in the episode Private Lives is when the character James Wilson confronts House as to why he was reading sermons (without pointing to the obvious that this reading was done secretly). The belief is that House was, indeed, looking for some logical, ethical, physical relationship with another person. In true form, House reverts to his atheist identity script by stating that he only found “God stuff” in the sermons. The attitude here is that the writings were trivial and held no further value. Is this reversal of perspective an abandonment of desire? Does House really believe that he has no physical connection to the extent that he relies on external logic and ethics? Did House come close to finding value and faith in his sermon readings that challenged his historic core atheist values? Though these are rhetorical questions, their place in the faith/belief system progression for the character House is important to present. Further, it is worth noting that this moment of faith/belief system construction was displayed for a major TV audience of 81.8 million viewers.

There is another phrase echoed throughout the Private Lives episode. Though this phrase is in reference to a colored past event in the college years of James Wilson, the phrase, “be not afraid” is a persistent refrain.

Who’s afraid?

“Be not afraid.” Had House elected to invest his faith/belief system in this agent of change, the outcome of the episode and House’s identity would each have been different. Embracing this simple charge, House could have come to grip his faith/belief questioning and seeking. An atomic revelation could have occurred within the psyche of House. Had this taken place, the future of the series would have led to a very different yet imaginable trajectory.

This hypothetical predicament yields questions that will go unanswered. In the end, House remained the love-hate atheist the series writers developed for the viewing audience. Still, in an episode where House comes close to exchanging the absence of faith for that of faith and the secondary theme is one cheering for change all seems more than a coincidence. Was it House that was afraid, or was the writers/producers afraid of House’s ability to change? Had House been liberated by not being afraid, perhaps his suggestion that life is not just a test may have rung true. Were House to have been courageous to change his faith/belief system, perhaps the “God stuff” would no longer be an easy excuse.

House may not have been afraid of rhetorical change. House may have been afraid of a logical-ethical-physical challenge to his core argument against firm theological discipline. Stoic philosophy did more than merely brush up against faith/belief systems in this episode. Yet, the resultant outcome was predictable. House codified his atheist reliance. In summary, House was afraid to know if there was more to life than just a conscious limited test. The narrative of the episode sought to bridge Stoic philosophy with the reality of faith/belief systems. But, just as House was not prepared with this proverbial leap of faith, so too the viewing audience may have been ill-equipped to see the value of this belief system change. Life continued for House as a test without a satisfactory answer key. Classical Stoic pillars/virtues overshadowed the companion theological virtues and Values-in-Action (VIA). House’s seeking for knowledge of faith/belief was reduced to a dramatic thread. By keeping House afraid of any “stuff,” pop culture was safe to know that their atheist hero would continue to hold a stereotypical mantle of Stoicism high throughout the remaining episodes. House lost in the struggle for his advancing faith/belief. We, the viewers lost in seeing the faith/belief growth of a favored character.

Drama simulacra drama.

Alan Lechsuza

https://www.patheos.com/blogs/thesweatpantsessions/

References

Blog Critics. https://blogcritics.org/faith-god-and-religion-on-house/ n.d.

Fandom.com. https://house.fandom.com/wiki/House_vs._God n.d.

Gospel Coalition. https://www.thegospelcoalition.org/reviews/free-ancient-guide-stoic-life/ n.d.

[H]ouse MD on religion. YouTube. 3 August 2013IMDB. House M.D.; episodes about religion ranked, 19 August 2021.

https://www.imdb.com/list/ls507932753/

Manz, Charles C. and Karen Manz. The Wisdom of Solomon at Work: Ancient Virtues for Living and Leading Today. Berret-Koehler, 15 January 2021.

Massive Attach, Teardrop (Instrumental), https://music.youtube.com/watch?v=Tb0MC0jFv6M

Michael B. quora.com. n.d.

Mitchell, Kerrie. The world’s most popular TV show is…’House’?. Entertainment Weekly, 12 June 2009.

Private Lives. House, M.D., Season 6, Ep. 14, March 8, 2010, https://house.fandom.com/wiki/Private_Lives

Peterson and Sellgman, qtd in Ruch, Willibald and Rene T. Proyer. Mapping strengths into virtues: the relation of the 24 VIA-strengths to six ubiquitous virtues, Frontiers Psychology, Vlm. 6, 21 April 2015, https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00460/full#:~:text=The%20study%20of%20various%20writings,et%20al.%2C%202005

Wikipedia. en.wikipedia.org>Gregory_House, 29 December 2023.

Image References

https://unsplash.com/s/photos/epictetus