Reviewing the abundance of articles written about the 1995 classic, Gangster’s Paradise by Coolio, there is more attention given to the production, the sample, the history and evolution of Coolio’s career, and the reference to gangster rap. With the opening lyrics quoting Psalm 23:4, it would be an obvious turn to critique the work from a theomusicological perspective. Yet, there is little written with this attention. Following the theomusicological work of Jon Michael Spencer, I propose to offer what is missing in the discourse of this Hip Hop and pop culture fixture.

Analyzing Paradise

Applying a critical comparative phenomenological theomusicological analysis, Gangster’s Paradise has the potential, of all works during its generation, to cross over from Hip Hop culture to a theomusicological work. The swath of Hip Hop productions during this era was reeling from the explosion of gangster rap and LA’s gangster culture. Such attention framed the stereotype of rap, which has been misapplied to Hip Hop culture. The degeneration of culture, a dystopian attitude, socio-economic oppression, heightened misogyny, drug, gang violence, and incarceration are a few of the common themes that defined this period of West Coast gangster Hip Hop. Pop culture romanticised these perspectives, and the Hip Hop industry exploited these on a mass market level, reaping a billion-dollar global industry. It was at this compressed time that Gangster’s Paradise rose to the top of the Billboard charts. Clean of explicit language, contextualized as an anthem for the soundtrack to the movie “Dangerous Minds,” Gangster’s Paradise was an anomaly for the time.

It was not the intent of Coolio, nor the accompanying producers, to author a border-crossing work, yet the invested potential of this work lends itself as a sonic bricolage. This manner of reading is highly overlooked by others who have written about Gangster’s Paradise.

Paradise By Coolio

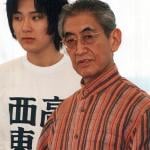

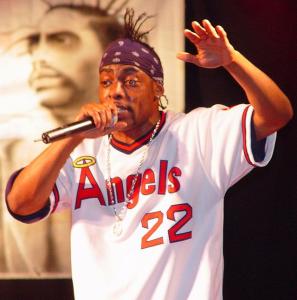

Coolio had a career in the late 1980s-early 1990s with two groups, WC and the Maad Circle. It became apparent early on that he was set to have a solo career and soon thereafter left Maad Circle. His first solo album, “It Takes a Thief,” was met with marginal success, ranking 8th spot on the Billboard 200 in 1994, with the well-known single “Fantastic Voyage” peaking at number 3 on the Billboard Hot 100 (Musicology blog, n.d.). His second album, “Gangsta’s Paradise,” released in 1995, was his breakthrough. The song went on to be an integral part of the film “Dangerous Minds,” which is troped in the video.

“The immense success of “Gangsta’s Paradise” cannot be overstated. The song topped the charts in 16 countries and became the United States’ best-selling single of 1995. It also earned Coolio a Grammy Award for Best Rap Solo Performance in 1996 and two MTV Video Music Awards for Best Rap Video and Best Video from a Film” (Musicology blog, n.d.).

Gangster’s Paradise owes its foundation to the early work by Stevie Wonder. Borrowing Stevie Wonder’s “Pastime Paradise,” Coolio’s work tropes on this theme and sonic landscape.

“The title track, [Gangster’s Paradise] produced by Doug Rasheed, sampled Stevie Wonder’s “Pastime Paradise” and delved into the struggles of gang life, offering a somber yet insightful look at the harsh realities faced by many in the inner city” (Musicology blog, n.d.).

Composer Doug Rasheed took the sample from the opening chorus of “Pastime Paradise” and reworked it. These were the sounds that caught Coolio’s attention. Altering the title to reflect the defeated landscape and attitude of the inner city, “Gangster’s Paradise” would embrace the haunting reality of the original Stevie Wonder track with a contemporary blend. Stevie Wonder would only allow the work to be covered with profanity removed, which made the final version of Gangster’s Paradise more acceptable to a larger audience base.

“Doug Rasheed…[w]ith a knack for blending hip-hop with orchestral elements, Rasheed skillfully crafted a musical masterpiece that continues to resonate with listeners worldwide. Beyond “Gangsta’s Paradise,” he has contributed to an array of memorable tracks, such as Tupac Shakur’s “Do for Love” and Snoop Dogg’s “Gangsta Move,” further solidifying his status as a highly sought-after producer in the industry. Rasheed’s ability to create evocative soundscapes that enhance the lyrics of each song truly makes him a standout composer in the world of hip-hop” (Musicology blog, n.d.).

Lyrics To Scripture

The work opens with a reference to Psalm 23:4,

Yeah, though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death, I will fear no evil; (NKJ).

This has not been disputed. However, the reference stops there, while the rest of Psalm 23:4 continues,

For You are with me; You rod and Your staff, they comfort me (NJK).

It is this point that is overlooked. Coolio only references the middle portion of the first sentence of this Psalm. If Gangster’s Paradise is considered to be a lament to living in a socio-economic oppressed environment, then limiting the review to only this first portion is consistent. However, there is hope within this work. Why does Coolio refer to praying in the night at the last line of the first verse?

“On my knees in the night, saying prayers in the streetlight”

The character refers to himself as being 23 years old and is unsure if he will make it to his 24th birthday.

“I’m twenty-three now, but will I live to see twenty-four/ The way things is goin’, I don’t know.”

There is a connection that presents a different reading of the work. The track opens with a reference to Psalm 23:4, a point of hope in the Psalm. Walking through trials and tribulations, the author of the Psalm, King David, positions this in the middle of the Psalm, a turning point away from defeat and leaning on the Lord for assistance to overcome the devastation of life.

“Psalm 23 – pain, strength, hope, and faith are delicately interwoven into these sincere lines that provide comfort to countless individuals throughout time (Ministry Voice, n.d.).”

“Psalm 23’s lyrics showcase how faith, trust, and divine providence are interlinked within the human experience and divine providence. Psalm 23 exemplifies this notion with each verse’s emphasis on finding inner peace while traversing this chaotic world (Ministry Voice, n.d.).”

If Coolio’s character – he was over 30 years old at the time this track was recorded – opens with this line, a turning point toward hope, then the character must be aware of the rest of the Psalm. Why is the second portion purposely removed?

The remainder of the Psalm is about hope and the grace that God gives to the one praying.

The LORD is my shepherd; I shall not want.

He makes me lie down in green pastures; He leads me beside quiet waters.

He restores my soul; He guides me in the paths of righteousness for the sake of His name.

Even though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death,

I will fear no evil, for You are with me; Your rod and Your staff, they comfort me.

You prepare a table before me in the presence of my enemies.

You anoint my head with oil; my cup overflows. Surely goodness and mercy will follow me all the days of my life, and I will dwell in the house of the LORD forever (NKJ).

Arguing Paradise

I argue that if Coolio’s character were to reference the rest of the Psalm, he would have to admit that, even though he is living in a troubled context, he is hopeful to be lifted from his circumstances. The character appears to be knowledgeable of scripture, at least this Psalm, and therefore has a tinge of hope embedded. Yet, if the character were to engage the rest of the Psalm, he would be going against the social pressures of the gangster lifestyle. He is threatened by the juxtaposition of the lived experience of a gangster’s life and the hope he prays for, at night, under the streetlight. The character is positioned in this middle space, which harkens back to slave narratives, where those in the middle passage, the Black Atlantic, would eventually write, sing, and storytell about their previous life while learning to embrace Christianity and translate their cultural traditions through this religious discipline as a way to understand the freedom through Christ as freedom from slavery. Coolio’s character is following this same lineage, which eventually became the black church and gave birth to gospel music. Following this analysis, the use of the gospel choir and the sermonizing voice of LV in the chorus is aptly applied. Gangster’s Paradise can be read as following this middle space, a middle passage from socio-political oppression and hegemony to one silently reaching for hope.

The complication remains in the voice of the character, who is firm on articulating his defeated position. I argue that Coolio’s character does so, as a narrative strategy, to confirm his dedication to his community and his lived experiences. It’s a mask behind which Coolio’s character hides his real intentions. Coolio’s character walks in similar footsteps as Nicodemus (John 3), who came to Jesus at night to learn how to gain the Kingdom. Coolio’s character prays at night under the streetlight, which is an obvious reference to the scripture. Continuing, Coolio’s character does not understand, believe, or have the faith to overcome his limited existence. He seeks the integral hope of Psalm 23, but does not understand this hope, as Nicodemus did not understand what Jesus was saying to him about being born again (John 3:3-12).

3 Now there was a Pharisee, a man named Nicodemus who was a member of the Jewish ruling council. 2 He came to Jesus at night and said, “Rabbi, we know that you are a teacher who has come from God. For no one could perform the signs you are doing if God were not with him.”

3 Jesus replied, “Very truly I tell you, no one can see the kingdom of God unless they are born again.”

4 “How can someone be born when they are old?” Nicodemus asked. “Surely they cannot enter a second time into their mother’s womb to be born!”

5 Jesus answered, “Very truly I tell you, no one can enter the kingdom of God unless they are born of water and the Spirit. 6 Flesh gives birth to flesh, but the Spirit gives birth to spirit. 7 You should not be surprised at my saying, ‘You must be born again.’

8 The wind blows wherever it pleases. You hear its sound, but you cannot tell where it comes from or where it is going. So it is with everyone born of the Spirit.”

9 “How can this be?” Nicodemus asked.

10 “You are Israel’s teacher,” said Jesus, “and do you not understand these things? 11 Very truly I tell you, we speak of what we know, and we testify to what we have seen, but still you people do not accept our testimony. 12 I have spoken to you of earthly things and you do not believe; how then will you believe if I speak of heavenly things? (NIV)

Limiting Paradise

What if Coolio’s paradise is the limited sense of absence of paradise? He frames the work through a sense of defeat. Paradise is popularized as a utopian concept. Yet, Coolio doesn’t see paradise in that manner. He longs for what he considers to be paradise, yet limits this state by his present context.

Paradise for Coolio is the present, not a longing future. His character is unable to articulate or conceive paradise, thus keeping him in a limited conscious state of defeat. He is akin to the rich man who asks how to enter the kingdom of heaven (Mark 10:17-31).

17 As Jesus was starting out on his way to Jerusalem, a man came running up to him, knelt down, and asked, “Good Teacher, what must I do to inherit eternal life?”

18 “Why do you call me good?” Jesus asked. “Only God is truly good. 19 But to answer your question, you know the commandments: ‘You must not murder. You must not commit adultery. You must not steal. You must not testify falsely. You must not cheat anyone. Honor your father and mother.”

20 “Teacher,” the man replied, “I’ve obeyed all these commandments since I was young.”

21 Looking at the man, Jesus felt genuine love for him. “There is still one thing you haven’t done,” he told him. “Go and sell all your possessions and give the money to the poor, and you will have treasure in heaven. Then come, follow me.”

22 At this the man’s face fell, and he went away sad, for he had many possessions.

23 Jesus looked around and said to his disciples, “How hard it is for the rich to enter the Kingdom of God!” 24 This amazed them. But Jesus said again, “Dear children, it is very hard to enter the Kingdom of God. 25 In fact, it is easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle than for a rich person to enter the Kingdom of God!” (Mark 10:17-31, NIV)

As the young rich man in the story, Coolio’s character is unable to release his possessions, a defeated life. When he is confronted with the reality of how to escape a socio-economically oppressed life, he turns away and returns to his current environment. It is here that Coolio’s character frames his defeated life and surroundings as a paradise, but one on earth, contextualized by gangster culture. The mask is fortified, socio-economic oppression is reified, and a gangster lifestyle is glorified. Coolio’s character performs this process daily as he exists in what he has come to articulate as a paradise, as marginal as it is.

To counterpoint this experienced reality, if Coolio’s character had continued to read and follow the hope of Psalm 23, he could be a metaphor of the thief on the cross who asks to be saved, is offered forgiveness, and enters into heaven with Jesus (Luke 23:39-43).

39 And one of the malefactors which were hanged railed on him, saying, If thou be Christ, save thyself and us.

40 But the other answering rebuked him, saying, Dost not thou fear God, seeing thou art in the same condemnation?

41 And we indeed justly; for we receive the due reward of our deeds: but this man hath done nothing amiss.

42 And he said unto Jesus, Lord, remember me when thou comest into thy kingdom.

43 And Jesus said unto him, Verily I say unto thee, Today shalt thou be with me in paradise (Luke 23:39-43, KJV)

Self-articulated Paradise

The track begins with a paraphrase of Psalm 23, “As I walk through the valley of the shadow of death…” This is the point of redemption for Coolio’s character. The following line articulates the character’s decision, “I take a look at my life and realize there’s nothin’ left…”

This turning point for the character comes at the start of the track. Seeing that Coolio’s character turns away from the opportunity of hope, he remains limited by his conscious earthly decision. When he tries by praying in the night (read: protected from the transparency of the day when no one can see him, or question his actions), he accepts his failures, rather than reading beyond the quoted lines of Psalm 23. The choir’s melancholy sonic landscape notes this personal defeat, and the hook by L.V. speaks to the audience of one.

“Been spendin’ most their lives livin’ in the gangsta’s paradise…” This frames the external as a shattered paradise.

“Keep spendin’ most our lives livin’ in the gangsta’s paradise…” This positions Coolio’s character in the shattered paradise.

“Tell me why are we so blind to see/ That the ones we hurt are you and me?” This is an inverted self-proclaimed analysis from Coolio’s character, but voiced by L.V. as an asking preacher.

Coolio positions paradise by his design, construction, and immediate environment. The character is crippled by the mask he has been wearing of a desire for hope, yet the external pressure is to be a role model for gangster culture. Paradise is not lost for Coolio’s character; it was never in existence. Biblical references to paradise are not conceivable for Coolio’s character as he turns away from the opportunity for personal reconciliation, forgiveness, and repentance provided in Psalm 23. The limited quote from that Psalm limits the character’s ability to accept what paradise can and is for him. The ambivalent space in which he resides, between an earthly gangster culture and the internal desire for hope, stunts his spiritual growth. The opportunity for repentance and acceptance of paradise is present, yet the character elects to define paradise through the active definition of gangster culture, thus making the gangster’s paradise his reality.