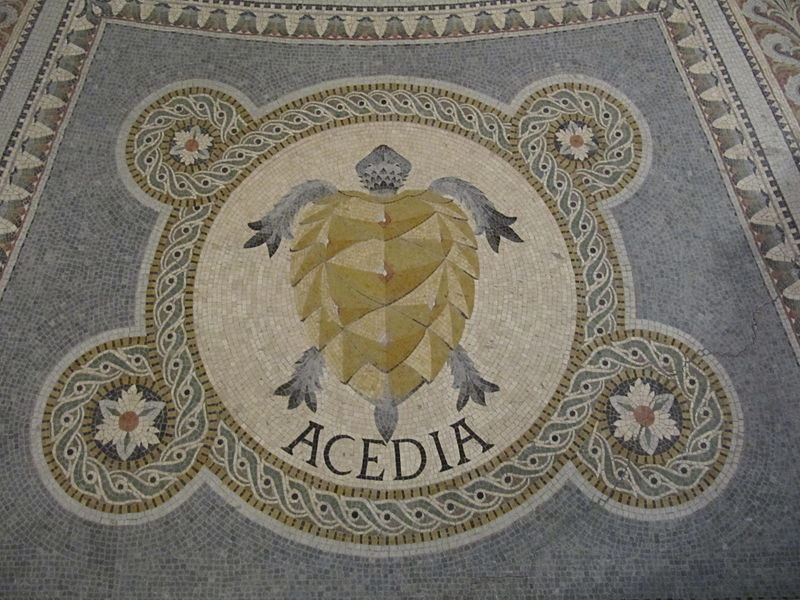

Уныние – мозаика, алтарная часть крипты базилики Нотр-Дам-де-Фурвьер, Лион, Франция – Rartat – Public Domain

“Very early on, the monastic tradition became interested in a strange and complex phenomenon: acedia. Spiritual sloth, sadness, and a disgust with the things of God, a loss of the meaning of life, despair of attaining salvation: acedia drives the monk to leave his cell and to flee intimacy with God, so as to seek here and there some compensation for the austere way of life to which he felt called by God. The psychological and spiritual subtlety of those who first studied this phenomenon – the Desert Fathers and Evagrius of Pontus in particular – cannot fail to challenge our contemporaries who, although they are no longer familiar with the term acedia, no doubt still experience the terrible symptoms of it. For acedia, the monastic sin par excellence, is certainly not to be considered as something from another era. On the contrary, might it not be the gloomy evil of our age?”

So begins Marc Cardinal Ouellet’s forward to The Noonday Devil: Acedia, The Unnamed Evil Of Our Times, by Jean-Charles Nault, O.S.B. I’m not yet even halfway through the book and I think I’d be forced to answer Ouellet’s question in the affirmative.

It bears repeating that acedia, or sloth, isn’t what we would call “laziness” in our market-frenzied world. This kind of sloth doesn’t have anything to do with not being economically productive or not having sufficient “use value” to society. A couch potato watching 12 hours of TV a day might (probably) suffer from acedia, but not because he lacks the vaunted Protestant Work Ethic. It’s more accurate to describe it as a sort of spiritual torpor that, through a devastating combination of melancholy, restlessness, and profound emptiness distracts people from seeking Christ.

The etymological history of the word is fascinating. The English word comes from the Latin acedia, which was borrowed from the Greek akèdia, and according to Nault is translated as “lack of care”. The Franciscan Bernard Forthomme explained in De l’acédie monastique è l’anxio-dépression that the word in the pre-Christian era was used to describe necessary funeral rights that had been abdicated. In other words, not burying the dead. It’s an essentially “inhuman” act that, rather than denoting the kind of “laziness” that we might mean when we use the word sloth colloquially, is instead more of an atonia, or relaxation of the soul.

Nault draws heavily from the writing of Evagrius of Pontus, and since I hope to write more about this subject tomorrow and this weekend, I’ll end this post with a quote from Evagrius that describes and defines acedia:

The demon of acedia, also called the noonday demon (cf. Ps. 90:6 Douay-Rheims), is the most oppressive of all the demons. He attacks the monk about the fourth hour [viz. 10 a.m.] and besieges his soul until the eighth hour [2 p.m.]. First of all, he makes it appear that the sun moves slowly or not at all, and that the day seems to be fifty hours long. Then he compels the monk to look constantly towards the windows, to jump out of the cell, to watch the sun to see how far it is from the ninth hour [3 p.m.], to look this way and that lest one of the brothers…[might have the good idea of coming to distract him from the monotony of his cell!]. And further, he instils in him a dislike for the place and for his state of life itself, for manual labour, and also the idea that love has disappeared from among the brothers and there is no one to console him. And should there be someone during those days who has offended the monk, this too the demon uses to add further to his dislike (of the place). He leads him on to a desire for other places where he can easily find the wherewithal to meet his needs and pursue a trade that is easier and more productive; he adds that pleasing the Lord is not a question of being in a particular place: for scripture says that the divinity can be worshipped everywhere (cf. John 4:21-4). He joins to these suggestions the memory of his close relations and of his former life; he depicts for him the long course of his lifetime, while bringing the burdens of asceticism before his eyes; and, as the saying has it, he deploys every device in order to have the monk leave his cell and flee the stadium. No other demon follows immediately after this one: a state of peace and ineffable joy ensues in the soul after this struggle.

Obviously there are spatial and temporal dimensions to acedia. More on that later/soon.