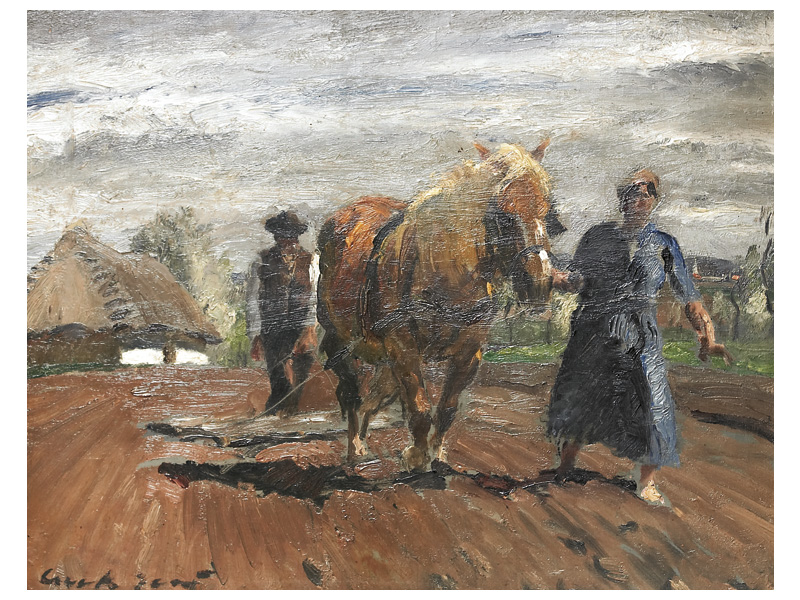

Csuk’s “Harrowing” – axioart – PD-US

I feel like we’ve been stuck in Aquinas’ thought for a few weeks now. Maybe “stuck” isn’t the right word, maybe a more appropriate phrase might be “privileged to occupy” or something. And it makes sense that we (and Nault himself, the impetus for this deep dive) would spend so much time with Saint Thomas: 1. His work is complicated and demands a slow meander 2. His work is relevant and rewards a slow meander. That said, let’s move on to Saint Thomas’ second definition of acedia, disgust with activity, or taedium operandi.

This second definition of acedia stands in contrast to the first, a sadness with God, in that it has to do not with a misplaced valuing of final ends (valuing other things over a friendship with God), but reticence to bring action to a conclusion. Nault says that this second definition of acedia contains within it “an interpretive key to all moral theology”. A big claim, so let’s explore what he means.

Like I’ve said, to understand one thing about Saint Thomas’ thought requires you to understand ideally all of the rest of it, but certainly a lot more than just the atomized section you’re looking at. The term “system” is a bit cool and abstract a description of his thought – maybe “organically cohesive” might work better. You can’t understand how the human hand works without also understanding skin, bones, the nervous system, blood flow, etc. It’s the same with Saint Thomas’ cathedral of thought. And in order to understand this second aspect of acedia, we have to return to his writing on beatitude. Thomas makes a distinction (a nearly arbitrary one, by his own admission) between “the object of beatitude itself” and “the process by which the soul is blessed”. Why the distinction is redundant seems obvious, but Saint Thomas makes it in order to underscore the idea that beatitude itself is a verb, an act, and doesn’t exist merely in “static repose” (requiem aeternam). “Now the perfection of a being consists in its being in act,” Nault writes, “because potency without act remains imperfect.” The point here is that action is vital to the morality of Saint Thomas. Nault calls it a “morality of excellent activity“, with virtue acting as the principle of the act – therefore rendering excellence on both the act and person acting.

So our actions always move us in a direction. That direction is either closer or further from God, depending on the orientation of those actions. But, of course, God is already always there (shades of Augustines “closer to me than I am to myself” here) – so the acts of man reveal to man the nature of God. As Nault writes, “The activity of man – particularly of the saints – reveals a true reflection of God’s face. There is an original character to the lives of the saints in which the mystery of God is reflected.”

It should be pretty obvious now how acedia and hatred of activity would relate to the beatitudes. There simply would be no opportunity for man to acquaint himself with God if right-oriented actions are stifled.

So there’s definitely a lot more to talk about here, but the next topic (VIRTUE IS NOT A HABIT) deserves a post all to itself.