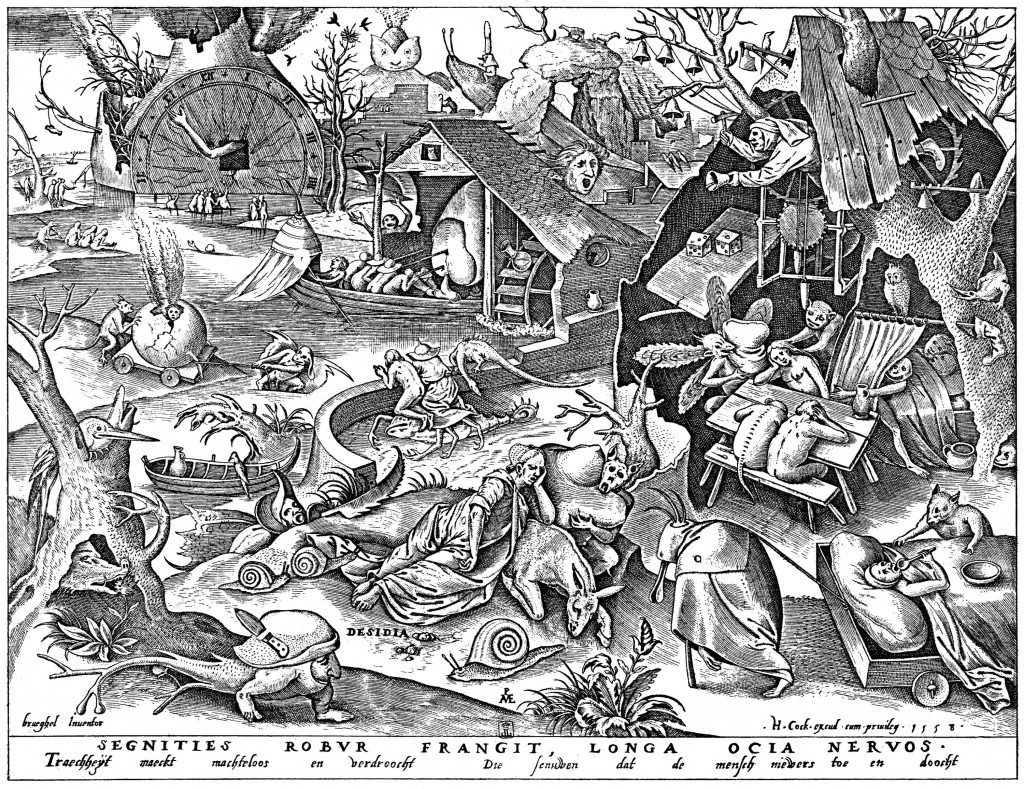

Brueghel: The Seven Virtues – Bibliothèque Royale, Cabinet Estampes, Brüssel – Public Domain

It almost seems foolish to present something as a “summary” of a Thomist idea. My months long exploration of acedia, profoundly punctuated by a self-introduction to Thomism, has been in large part a lesson in intellectual humility. Thomistic thought seems so fully integrated into itself that, if not impervious to dissection, it feels best understood used rather than explained – showing the thought in action rather than discussing the thought with its wings pinned to a piece of paper. Fortunately for you, poor reader, I’m such a novice that, not quite trusting myself to drive the car yet, you get to watch me fool around with the engine like a shade tree mechanic. I hope it’s as fun for you as it is for me.

So we know that Saint Thomas says love moves in a circular motion. And we move along with it. Jean-Charles Nault writes that “Saint Thomas’ profound insight is that we always act out of love, by being drawn, by attraction, to the Good.” This is how Saint Thomas depicts Freedom: a free movement towards the good. Remember here the metaphor of a musician who is “free” to play whatever they wan, including wrong notes, and the musician who is truly free – free to play well, and then to push towards the sublime.

The steps in this movement towards the Good are:

-An intentional union. An object has a profound effect on the subject.

-Then desire, which is a movement to adapt ourselves to the subject. The drive to make the potential union an actual union.

-Last a union with the object. This results in either happiness or true spiritual joy, gaudium.

The rub is not confusing lesser joy with the Good and to not become psychologically daunted by the grandeur and depth of human desire in its most profound application. Lowering his ambitions, man comes to accept what Saint Thomas termed “animal beatitudes” – things that are immediately attainable in this world. Nault writes, “In this sense, the Incarnation revives man’s hope by making him rediscover his dignity.”

When Saint Thomas’ circle of action and desire is applied to God (I guess you could say that this is its primal, formal, or original purpose, and that it only secondarily gets applied to lesser good), the last step in the cycle would be a direct encounter with Christ, after being called by God to desire such a union in the first place. The Holy Spirit makes possible Christ being the end motivation for every action – regardless of how wrongly oriented it might be.

Acedia is a theological vice, affecting all three theological virtues. It opposes faith in that it leaves you overwhelmed with the depth and scope of your true desire. It opposes hope because it engenders despair. And it opposes charity in so much as it baffles the joy of gaudium. Note that each of these correspond to the steps in Saint Thomas’ circular cycle of love. Things echo each other in his thought. Rafters dovetail perfectly with broad beams.

So how does Saint Thomas oppose acedia? Nault writes that we oppose it through wisdom, the savory science; “Wisdom develops in us the instinct of the Holy Spirit, who directs us interiorly.” Saint Thomas considered this in his commentary on Romans 14:8, “Those who are acted upon or driven (aguntur) by the Spirit of God, they are the children of God.” Saint Thomas reflects on that passive verb, aguntur, and what it could mean to be driven. Animals are driven by instinct. But Man, created in the image of God, is a creature with spiritual needs and a spiritual character. But the saints, he reasons, are both driven by themselves and at the same time acted upon by the non-carnal instincts of the Holy Spirit. His entire response to acedia is maybe best summed up in having the wisdom to let the Holy Spirit act upon and guide us.

Next up: William of Ockham. And heads up, I’m not so taken with him.