Intellectual dishonesty and moral laziness often are at the heart of political debate. People from various political positions justify their position on little to no logic. Indeed, there are two common ways of dealing with social issues which are found throughout the political spectrum, and both must be rejected.

The first kind of response is simple: I have proven you wrong, therefore I must be right. This kind of response often comes from the fact that people tend to have a very dualistic understanding of the world, and they think that there are one of two possible ways of dealing with things. This means that if you can prove A is not right, then you have proven B is correct. In America, this often seen in political rhetoric. We are led to believe that answers to the nation’s problems must come from a politician representing one of two political parties: the Republicans or the Democrats. If you can show Republicans are wrong for going to war in Iraq, you then prove Democrats are right; if you can show Democrats are evil for supporting abortion, you then prove Republicans are good, wholesome people.

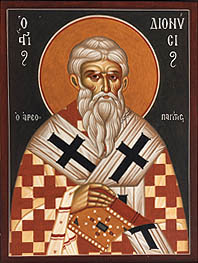

This way of looking at things often seems to make sense. Yet, if one critically examined the situation, they should be able to see how false this line of thought actually is. Pseudo-Dionysius explains the problem well when he writes, “Do not count it a triumph, reverend Sosipater, that you are denouncing a cult or a point of view which does not seem to be good. And do not imagine that, having thoroughly refuted it, all is therefore well with Sosipater. For it could happen that one hidden truth could escape both you and others in the midst of falsehoods and appearances. What is not red does not have to be white. What is not a horse is not necessarily a human” Pseudo-Dionysius, “Letter Six” in Pseudo-Dionysius: The Complete Works. trans. Colm Luibheid (New York: Paulist Press, 1987), 266.

This way of looking at things often seems to make sense. Yet, if one critically examined the situation, they should be able to see how false this line of thought actually is. Pseudo-Dionysius explains the problem well when he writes, “Do not count it a triumph, reverend Sosipater, that you are denouncing a cult or a point of view which does not seem to be good. And do not imagine that, having thoroughly refuted it, all is therefore well with Sosipater. For it could happen that one hidden truth could escape both you and others in the midst of falsehoods and appearances. What is not red does not have to be white. What is not a horse is not necessarily a human” Pseudo-Dionysius, “Letter Six” in Pseudo-Dionysius: The Complete Works. trans. Colm Luibheid (New York: Paulist Press, 1987), 266.

Now the general populace is probably not culpable for following this line of thought, because they have been raised to accept it, and have not been given the skills, or the time, to think beyond it. But those politicians who do know that this kind of reasoning is wrong and yet and still use it demonstrate how dishonest they are willing to be for the sake of personal gain. While it might prove useful, utility does not justify dishonesty; the morality of one who continues to use this kind of rhetoric, when they know it is erroneous, is questionable at best.

The morality of the second position is even more questionable. It deals with social problems in this fashion: unless you can provide a solution, don’t criticize what is being done (or, if nothing is being done, don’t point out that nothing is being done). It’s like saying if you can’t find a solution to poverty, don’t point out that killing the poor is evil.

This kind of answer can only come from a moral reprobate who does not care that evil is being done in the name of the good. “Woe unto them that call evil good, and good evil” (Isaiah 5:20). Such a utilitarian reasoning is never used by those who actually care for the good. If they see the error of a given practice, they will try to have it stopped. It’s why Christians cannot accept the response, “Well, the woman is impoverished, and she couldn’t deal with raising a child” as an excuse for abortion. While they must agree with the fact that hardships will exist for such a woman, and for the child, abortion is not the answer. Something else must be found. Christians are required to work for a proper solution to the situation. The same, however, must also be said with other social issues. “Well, if you don’t support the Iraq war, tell me how you would have dealt with Saddam Hussein.” Even if one doesn’t know what one could do to deal with Iraq, that does not justify invading Iraq. Clearly, as Pope Benedict has said recently, we need to work for new models and new ways of dealing with such situations, and we cannot allow old ways, which have proven to be wrong, to continue just because it is seems to be an easy way out. The consequences of doing evil show that, despite all initial appearances, it is never the easy way out. If one is not capable of recognizing the problem, and what solutions are not acceptable, one will never be able to find the real answer. It might take time, it might take cooperation, it might take humility, it might even take mercy and forgiveness, but in the end, the only legitimate solution is one which meets all moral criteria, no matter how difficult it is to live up to it. Just because one has not, at one given time, found the answer does not mean it is not there; and it certainly does not justify the utilitarian approach which is commonly held by politicians.

In the end, we need moral politicians. To be a person of character is to be someone who is willing to sacrifice their own security, their own pleasure, their own temporal happiness, if all of these come from evil. That is the problem many of us face. Until there is a true conversion of heart, until the mechanizations of sin in the world are faced down for what they are, and the fruit of sin is recognized for what it is, there will be no true solution. It is why the Christian must always stand firm with their values, and why moral compromise can never be justified.