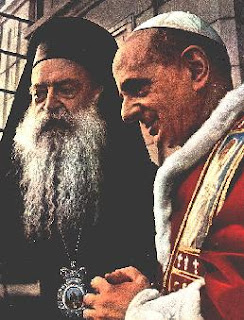

“God Himself took the initiative in the dialogue of salvation. ‘He hath first loved us.’ We, therefore, must be the first to ask for a dialogue with men, without waiting to be summoned to it by others” Pope Paul VI, Ecclesiam Suam (Vatican: 08-06-1974), par. 72. Dialogue between God and humanity provides the means by which we can go and dialogue with others about God. All of us encounter God in many different ways. We might not always realize when God is talking to us, or understand how to interpret what He says (which explains why many think God is silent in their lives). Yet we can, and should, use God’s dialogue with humanity as the basis for our own dialogue with each other about God.

“God Himself took the initiative in the dialogue of salvation. ‘He hath first loved us.’ We, therefore, must be the first to ask for a dialogue with men, without waiting to be summoned to it by others” Pope Paul VI, Ecclesiam Suam (Vatican: 08-06-1974), par. 72. Dialogue between God and humanity provides the means by which we can go and dialogue with others about God. All of us encounter God in many different ways. We might not always realize when God is talking to us, or understand how to interpret what He says (which explains why many think God is silent in their lives). Yet we can, and should, use God’s dialogue with humanity as the basis for our own dialogue with each other about God.

Perhaps the first and most common encounter we have with God is internal. When we examine the values we hold most dear and discern why this is so, we find out that the reason is because God is at work, gently guiding us, trying to get us to follow His higher standards. “In the depths of his conscience, man detects a law which he does not impose upon himself, but which holds him to obedience. Always summoning him to love good and avoid evil, the voice of conscience when necessary speaks to his heart: do this, shun that. For man has in his heart a law written by God; to obey it is the very dignity of man; according to it he will be judged” Gaudium et Spes (Vatican: 12-7-1965), par. 16. No matter how muffled the voice has become, no matter how many layers of filth we have put over it to hide the dictate of this voice in our life, the voice is always there, always talking to us. “Conscience is the most secret core and sanctuary of a man. There he is alone with God, Whose voice echoes in his depths” Gaudium et Spes, par. 16.

In a sense, inter-religious dialogue begins when two or more people meet, realize that they both have encountered God’s voice in their lives, and share their experiences with God with one another. Their understanding of that voice, even if they come from the same religious tradition, will not be the same. We could find many reasons for this, as for example, the intellectual ability, religious education, or spiritual preparation of a given individual will provide for different hermeneutical approaches to the experience of God. Yet, in their dialogue, they can come to realize that they share the voice of God in common, and this could provide the means by which they find some sort of unity between them. While we must not think that the development of a given religious tradition was entirely irenic, because of course, as a whole most this was not the case, yet, we must also understand that the role of dialogue (and debate) in the history of a religious tradition provided the means by which that tradition was established. It also formed the basis by which the religious experiences people had were explained by that religious tradition. From this we can then understand why people of one religious tradition seek to dialogue with people of other religious traditions: because, in a sense, all religions are founded upon such dialogue and continue to thrive and evolve by it.

We must not take this analogy too far. Some people believe inter-religious dialogue is aimed towards the creation of a one-world religion, and that this religion will be based upon what all religions hold in common and nothing else. Others, also believing that inter-religious dialogue aims for a one-world religion, think it does so, not by trying to find one common denominator, but by trying to syncretically jumble all religions together into one monstrous religion. Neither of these, however, are the objective of inter-religious dialogue. Inter-religious dialogue does not want to create a one world religion. But if this is the case, then what is it trying to do? What are the possible goals of inter-religious dialogue?

Inter-religious dialogue aims at establishing a better understanding of world religions, that is, it wants to overcome erroneous views people have about various religious traditions by rejecting one-sided, polemical presentations of these faiths. In place of such biased presentations which people have had in the past, it wants to allow people who hold a given faith to be witnesses of that faith, to proclaim what it is their faith truly believes. Inter-religious dialogue also seeks to find ways members of various religious traditions can work together in the world we live in for the sake of the common good. Or, as Cardinal Arinze describes it, “Interreligious dialogue is a meeting of people of differing religions, in an atmosphere of freedom and openness, in order to listen to the other, to try to understand that person’s religion, and hopefully to seek possibilities of collaboration. It is hoped that the other partner will reciprocate, because dialogue should be marked by a two-way and not a one-way movement” Francis Cardinal Arinze, Meeting Other Believers (Huntington, Indiana: OurSundayVistor, 1997), 16.

It is in the area of collaboration that many people find inter-religious dialogue most problematic. Indeed, critics of inter-religious dialogue often ask two specific questions: Will the members of the dialogue collaborate in the creation of inter-religious truths? Will the members of the dialogue pray together to a large pantheon of gods and goddesses? Clearly these questions are important, but if one actually reads the literature written by those involved in inter-religious dialogue, one will recognize that these concerns are raised not only by the critics of inter-religious dialogue, but by those who participate in the dialogues themselves. Inter-religious dialogue is about the meeting of people of different religious traditions, where they get to know each other, and find those areas where they can work together, certainly, but for this to be true, the members of the dialogue also have to be true to themselves and to their own religious faith. The dialogue would not be true to the religious traditions involved if the members of the dialogue repudiate their own tradition and ignore significant parts of it in order to engage in the dialogue. “It would be pretense to affirm that I do not know or am not convinced of my certainties. I cannot simply abstract my deepest convictions or concoct the fiction that I have forgotten or laid aside what I hold to be true” Raimon Panikkar, The Intra-Religious Dialogue (New York: Paulist Press, 1999), 78. Thus the dialogue does not seek to replace or contradict one’s religious teachings for the sake of harmony; it seeks to find a way that people of different religious traditions can work together in the world respecting each other in spite of religious differences.

It is in the area of collaboration that many people find inter-religious dialogue most problematic. Indeed, critics of inter-religious dialogue often ask two specific questions: Will the members of the dialogue collaborate in the creation of inter-religious truths? Will the members of the dialogue pray together to a large pantheon of gods and goddesses? Clearly these questions are important, but if one actually reads the literature written by those involved in inter-religious dialogue, one will recognize that these concerns are raised not only by the critics of inter-religious dialogue, but by those who participate in the dialogues themselves. Inter-religious dialogue is about the meeting of people of different religious traditions, where they get to know each other, and find those areas where they can work together, certainly, but for this to be true, the members of the dialogue also have to be true to themselves and to their own religious faith. The dialogue would not be true to the religious traditions involved if the members of the dialogue repudiate their own tradition and ignore significant parts of it in order to engage in the dialogue. “It would be pretense to affirm that I do not know or am not convinced of my certainties. I cannot simply abstract my deepest convictions or concoct the fiction that I have forgotten or laid aside what I hold to be true” Raimon Panikkar, The Intra-Religious Dialogue (New York: Paulist Press, 1999), 78. Thus the dialogue does not seek to replace or contradict one’s religious teachings for the sake of harmony; it seeks to find a way that people of different religious traditions can work together in the world respecting each other in spite of religious differences.

Indeed, if someone were quick to renounce their own religious tradition, and its core teachings, thinking this were necessary to engage in inter-religious dialogue, it would show that they are no longer a follower of that religious tradition; thus, they could not faithfully represent it in inter-religious dialogues. “Interreligious dialogue is therefore not for religious indifferentists, not for those who are problem children in their faith community, not for academicians who entertain doubt about some fundamental articles in their faith, nor for religious iconoclasts who have already shattered sacred statues and shaken some of the pillars on which their religion is built” Francis Cardinal Arinze, Religions For Peace (New York: Doubleday, 2002), 51. Those interested in inter-religious dialogue want to know the opinions and beliefs of people from other religious traditions. They do not want to engage someone who questions their own religious tradition, because, as anyone knows, such people would give a skewed interpretation of that religious tradition. Only someone who truly believes in their religious faith would present it in the best possible way.

There is a danger in taking this line of thought too far: most people, even people of great faith, have times in their lives where doubts creep in. Indeed, some of the people with the greatest faith can be the same people who have wrestled with the greatest amount of doubt. It is not doubt, but infidelity, and the willingness to abandon the basic tenets of one’s faith, which is the problem. But even here, we must be careful. It is a given that we are imperfect, and the presentations will be imperfect. It is how that imperfection manifests itself which is the point.

Moreover, we do not want to say that people who have grave doubts of their own religious faith should never be involved in any inter-faith dialogues. There are different kinds of dialogues and different levels of representation one can bring to such dialogues. If there is an official meeting between members of the Christian and Muslim religions, the dialogue members have a different level of responsibility than if the dialogue were an unofficial meeting of friends who just want to learn from each other each other’s beliefs. In the second case, unless the friends were also specifically trained experts in their religious traditions, the conditions of the meeting must also include an understanding of the limits of the individuals involved to discuss all aspects of their faith. Yet this kind of dialogue is at least as important as official dialogue. And in this second category, it is clear that there will be people who have doubts and even criticisms of their own religious tradition; if this is the case, they should let that be known in the dialogue; clearly they still possess insights which would provide for a significant contribution in the discussion at hand, and so they should participate in it; but they must recognize the fact that, when discussing their own private concerns, they cease to be representatives of a specific religious tradition and become, as it were, representatives of their own private belief.

Inter-religious dialogue, which is often engaged on a daily basis by the mere fact that people of different religious traditions work together, and discuss their faith and values with one another, has many ways it manifests itself. Not all dialogues are doctrinal; indeed, the great majority of them, those done on a daily basis, rarely probe doctrinal questions, and when they are addressed, the answers provided usually end up being very superficial because the circumstances of the dialogue do not allow anything more. Nor do they have to, because the format of such common dialogues is aimed at getting to know believers of other faiths, to know the believers as people who can be trusted and respected in their own right. It is highly personal, because, on the one hand, we come to realize the influence of one’s religious tradition on the development of a person, and so there is clearly an intellectual aspect to the encounter, but on the other hand, we can see that the person is still a person: they are not an automaton who is given no free will in their religious tradition. We eventually come to realize people of other religious traditions as a person when we see them as “The thou as a source of self-understanding that I cannot assimilate from my own perspective alone” Raimon Panikkar, The Intra-Religious Dialogue, 37. This desire to see others as people who can be and should be respected despite their religious and cultural difference to our own is an important, indeed, necessary level of inter-religious dialogue because it helps eliminate notions of “strangeness” or “difference” that can cause xenophobia and religious prejudice – the kind of bias that, for example, hurt many of the Irish Catholics after their immigration to the United States.

Through their own work and encounters with people of other religious traditions, Catholic leaders engaged in inter-religious dialogue have mapped out four ways inter-religious dialogue generally takes place. In the important document, Dialogue and Proclamation, co-produced by the Pontifical Council for Interreligious Dialogue and the Congregation for Evangelization of Peoples, these four kinds of inter-religious dialogue are explained thusly:

a) The dialogue of life, where people strive to live in an open and neighbourly spirit, sharing their joys and sorrows, their human problems and preoccupations.

b) The dialogue of action, in which Christians and others collaborate for the integral development and liberation of people.

c) The dialogue of theological exchange, where specialists seek to deepen their understanding of their respective religious heritages, and to appreciate each other’s spiritual values.

d) The dialogue of religious experiencee, where persons, rooted in their own religious traditions, share their spiritual riches, for instance with regard to prayer and contemplation, faith and ways of searching for God or the Absolute.

—Dialogue and Proclamation (Vatican: 5-19-1991), par. 42.

We must understand that these forms of dialogue are interdependent with one another. One can and probably should focus on one kind of dialogue at a given time, but the other kinds are likely to appear, and should appear, when one is engaged in inter-religious dialogue. As Cardinal Arinze points out, “It is clear that the above forms of dialogue do not exclude one another, that no one is expected to practice all forms in all circumstances, but that whenever a believer meets another of a different religious conviction, at least one form of dialogue is possible” Francis Cardinal Arinze, Meeting Other Believers, 20.

We must understand that these forms of dialogue are interdependent with one another. One can and probably should focus on one kind of dialogue at a given time, but the other kinds are likely to appear, and should appear, when one is engaged in inter-religious dialogue. As Cardinal Arinze points out, “It is clear that the above forms of dialogue do not exclude one another, that no one is expected to practice all forms in all circumstances, but that whenever a believer meets another of a different religious conviction, at least one form of dialogue is possible” Francis Cardinal Arinze, Meeting Other Believers, 20.

It is also clear, that in examining these categories, some kinds of dialogue are more common than others. Throughout my presentation, I have discussed the dialogue of life and dialogue of action more than the dialogue of theological exchange and dialogue of religious experience, because they are the ones which anyone can actively participate in without any specific study, research and experience. Indeed, some of them might require the use of skills that so-called religious experts might not possess. These kinds of dialogues also help form the desire to know more about those we work with, to actually want to know about their religious faith. It opens us up so that we are willing to listen to members of other religious tradition instead of just assuming our limited knowledge and understanding of their faith sufficiently categorizes it. They also highlight and important fact which cannot be repeated enough: “Were it to be reduced to theological exchange, dialogue might easily be taken as a sort of luxury item in the Church’s mission, a domain reserved for specialists. On the contrary, guided by the Pope and their bishops, all local Churches, and all the members of these Churches, are called to dialogue, though not all in the same way” Dialogue and Proclamation, par. 43.

Of course this is not to say any inter-religious dialogue is easy; even the dialogue of life requires much effort by those who actively engage it. “Though dialogue of life may appear to be spontaneous, it does require an effort – the definition quoted above uses the word ‘strive’. It is easy to close in on oneself and ignore the other, especially if the other belongs to a rather closed community, which apparently does not want this dialogue. It requires perseverance to overcome the barriers of diffidence and suspicion” Michael L. Fitzgerald and John Borelli, Interfaith Dialogue: A Catholic View (Maryknoll, New York: Orbis Books, 2006), 75.

Just because it is difficult does not mean it should be avoided; indeed, the difficulties which we face as a world community if people of other faiths do not actively engage each other and get to know each other on this personal level demonstrate why inter-religious dialogue must be a recognized aspect of the Christian experience. Just as Christianity was misunderstood by many Romans, because Christianity was new and seemed strange to the Romans, so too many other religious traditions are often misunderstood by us because of how strange they seem to us. Inter-religious dialogue works to overcome this disposition, so instead of seeing people of other religious traditions in the eyes of polemics, we get to see them, for the most part, as people like us, who, like us, want to live a good, moral life in peace. Certainly there will be some who are not so benign, but this is true, not only for people from non-Christian traditions, but for Christians as well. We would not want people to judge us by the vilest representatives of Christianity, so too, we should not judge other religious traditions by their equivalents.

It is easy to believe misrepresentations and fear followers other religious traditions if you do not actively engage them. But when you get to know the people who follow other religious beliefs, and see they are, like us, people trying to do good in the world, you will be less likely to believe the polemics which aims to see them, not as people, but as monsters which need to be destroyed. After all, such polemics have a way of being two-ways, and your own actions against them becomes the foundation for polemics against your religious faith.

Of course we will find things we disagree with them if we are faithful to our own religious tradition, and indeed, not everything in their religious tradition will be something we consider to be benign. However, if we are honest, we will also admit the history of our own religious tradition is not pure, and this explains why the Church needs to be constantly reformed, to preserve and protect it from the sins of its members. When we encounter our own religious tradition by the eyes of an outsider questioning it, not out of disrespect but out of a desire to know and comprehend it, we will also find it helps illuminate issues which we would otherwise not see so clearly as needing to be addressed.