I am eagerly awaiting Paul Krugman’s new book (Krugman, by the way, will almost certainly win a Nobel prize in economics some day) on the politics and economics of inequality. This post is a follow up to yesterday’s on economics and the common good, and will argue that rising inequality is definitely something that should concern Catholics, as the unequal division of resources has been condemned consistently by Catholic social teaching.

Here is a nice diagram, depicting the share of the richest 10 pecent in national income, from Krugman’s blog:

This really says it all. During the long gilded age, income was highly unequal. It was a period of rapid wealth creation that simply was not shared. A dominant ideology of laissez-faire liberalism justified these outcomes as based on efficiency, economic freedom, and the moral superiority of market outcomes. The elites were politically dominant, and did little to alleviate close the gap between extremes of wealth and poverty. What Krugman calls the Great Compression was the fall in inequality that accompanied the New Deal, and continued into the post war period. “Middle Class America” was the period that many now remember fondly, where the rewards of a robust economy were shared broadly. This lasted until the late 1970s, and the rise of Reagan.

Since then, America has entered a second gilded age, as levels of income and wealth inequality rose to levels not seen since the 1930s. As Krugman notes, the real income of the median household (the best measure of middle-class living standards) rose only 13 percent since 1979, but the income of the richest 0.1% of Americans rose 296 percent over the same period. The top hundredth of the US population had an 8 percent income share in 1980, and this rose to 16 per cent by 2004. As profits rose dramatically, the wage share of national income declined in tandem. Another point to note is that growth was actually higher in the earlier period (the average growth rate between 1960-1979 was around 4 percent, as opposed to 3 period in the period thereafter). Clearly, a more stable and equal society is perfectly compatible with a vibrant economy, despite what the laissez-faire ideologues might claim.

But should we care? This is the basic question. Some will argue that if the rich get richer, and the poor and middle class are no worse off, then welfare as a whole has improved. This is classic utilitarianism, the “greatest good of the greatest number”, and is not at all compatible with Catholic social teaching that emphasizes human dignity above all else. A second argument is the Reaganite “trickle down” position: provide incentives for wealth creation (especially by cutting taxes on the rich) and all will benefit. But this did not happen, as living standards stagnated. Yet another argument is that the living standards of the poor and middle class are vastly greater than during the last gilded age, so we should not worry so much. This position holds that what matters is absolute rather than relative poverty, and certainly has some merit. See here for a gripping account of the reality of life in 1900, written by Berkeley economist Brad DeLong. Life was truly very different and vastly more difficult. Still, this argument is lacking. Somebody in 1900 could have easily made the same point about the conditions of the working class in that time and place, versus some time of great deprivation in the past. In a nutshell, this argument basically amounts to telling a person to be satisfied with his lot, as his predecessors had it far worse.

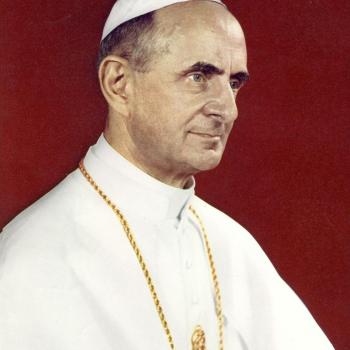

Catholic social teaching is instead concerned with the common good in present circumstances, in the here-and-now. The notion of solidarity, that the gains from economic progress be shared, is a central one. Popes Leo XIII and Pius XI in particular denounced both liberalism and socialism in equal measure (the latter referred to them as the “twin rocks of shipwreck”), calling instead a sharing of wealth between capitalists and workers. For, as Aquinas noted, the right to private property is by no means absolute, as the right to possess property is distinct from its use. It is for this reason that the principle of the “universal destination of goods” takes pride of place in Catholic economic thinking. This of course, as noted by Leo, opens the door to the role of the state, where, in protecting the rights of private individuals, chief consideration in the pursuit of the common good is given to the weak and the poor.

From this basis, the Church called a sharing of good between the classes. As noted by Pope Leo, “the wealth of nations originates from no other source than from the labor of workers”. Since both capital and labor cannot function without each other, neither should attempt to abrogate the fruits of production to itself. But at same time, the popes noted, capital did indeed appropriate far too much for itself. As Pius XI wrote: “riches that economic-social developments constantly increase ought to be so distributed among individual persons and classes that the common advantage of all…. one class is forbidden to exclude the other from sharing in the benefits.” Ideally, workers would “share in the ownership or management or participate in some fashion in the profits received”. The most basic concern is that workers be payed a sufficient family wage.

Although they lived in different times, I believe the teaching of Popes Leo XIII and Pius XI offers powerful lessons to the economic situation of today. Rerum Novarum and Quadragesimo Anno were written in 1891 and 1931 respectively, spanning the period of the first gilded age. In the present era, as wages stagnate as profits soar, the voices of past pontiffs echo prophetically in our consciences. For again, we have one class excluding the other from the benefits of growth and prosperity. Once again, the right to private property is seen as absolute, as progressive taxation is opposed vigorously. Once again, the rights of workers to organize are being chipped away by legal system. In a time of abundant wealth, workers struggle to earn a family wage and to stay financially afloat, and two-income families are a practical necessity. At the same time, a small handful are awash in great riches. And just as during the first gilded age, as pointed out by Lew Daly, a reigning ideology of laissez-faire liberalism holds sway, where the outcome of the marketplace becomes the moral norm and the state has no right to rectify things. I think Catholic social teaching would respectfully disagree.

Just think of Pope Pius XI’s castigation of the capitalist economic system of 1931, with its direct and stark language, and notice how much again rings true today:

” In the first place, it is obvious that not only is wealth concentrated in our times but an immense power and despotic economic dictatorship is consolidated in the hands of a few, who often are not owners but only the trustees and managing directors of invested funds which they administer according to their own arbitrary will and pleasure. This dictatorship is being most forcibly exercised by those who, since they hold the money and completely control it, control credit also and rule the lending of money. This concentration of power and might, the characteristic mark, as it were, of contemporary economic life, is the fruit that the unlimited freedom of struggle among competitors has of its own nature produced, and which lets only the strongest survive; and this is often the same as saying, those who fight the most violently, those who give least heed to their conscience.

This accumulation of might and of power generates in turn three kinds of conflict. First, there is the struggle for economic supremacy itself; then there is the bitter fight to gain supremacy over the State in order to use in economic struggles its resources and authority; finally there is conflict between States themselves, not only because countries employ their power and shape their policies to promote every economic advantage of their citizens, but also because they seek to decide political controversies that arise among nations through the use of their economic supremacy and strength.”

And finally, note the US bishops’ admonition of capitalism in 1919 (sourced from Daly’s paper):

“He [the capitalist] needs to learn the long-forgotten truth that wealth is stewardship, that profit making is not the basic justification of business enterprise, and that there are such things as fair profits, fair interest, and fair prices. Above and before all, he must cultivate and strengthen within his mind the truth which many of his class have begun to grasp for the first time during this present war; namely, that the laborer is a human being, not merely an instrument of production; and that the laborer’s right to a decent livelihood is the first moral charge upon industry. The employer has a right to get a reasonable living out of his business, but he has no right to interest on his investment until his employees have obtained at least living wages. This is the human and Christian, in contrast with the purely commercial and pagan, ethics of industry”

And yet, in this era where Reagan is held up as a model of virtue, I fear this kind of rhetoric would be attacked as dangerous leftist demagoguery. That should tell us something about the neglect of Catholic social teaching in today’s debate.