Previous in Series: Racism without Race?

Start with a question that at first glance may seem far removed from matters of race and racism: why do teenagers pay higher rates for car insurance than do other drivers? The answer, obviously, is that they have a higher rate of accidents. Note, though, that a particular teenager will still be a higher rate even if he happens to be an excellent driver and will never get into an accident. Why? Because while a particular teenager might be safe, many of his peers are reckless and/or inexperienced, and it is not possible for the insurance companies to distinguish him from the others. To the extent that there was a low cost way of distinguishing between good drivers and bad drivers, insurance companies would use it, and in fact teen drivers do often pay more or less for insurance depending on their sex, because it turns out that teenage boys get into a lot more accidents than teenage girls.

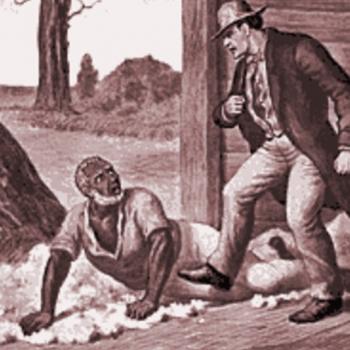

This process is known as statistical discrimination, and in many areas of life it is considered unobjectionable. Yet, as with so many other things, when it comes to race matters are different.

In my last post, I mentioned an experiment in which students used statistical discrimination to pick who to hire based on the different average education levels of randomly assigned “green” or “purple” students. Despite the fact that “green” and “purple” were not pre-existing categories, many people seemed inclined to call what the “employer” students did racist. Interestingly, no one considered the actions of the employee students to be racist, even though it was based on exactly the same statistical calculation as the student employers. I suspect that, if the two randomly assigned groups had been called “left” and “right” rather than “green” and “purple,” people would have been less likely to consider what the student employers did racist. But whatever one thinks about that particular example, if a real employer were to use the same method to not hire real racial minorities, few would doubt that this was racist.

And therein lies the rub. For to engage in this sort of statistical discrimination, one needn’t be motivated by any sort of animus or hatred of a particular racial group.

Nor is statistical discrimination the only case in which racial discrimination can be “rational,” at least in terms of one’s narrow self-interest. Consider, for example, a white restaurant owner in 1920s America. This owner may harbor no particular animus against blacks. He may even wish that he could get their business. Yet in all likelihood he will have a policy not to serve blacks in his restaurant. Why? Because he knows that if he does so, whites will stop frequenting his establishment, and he will not be able to make up this lost business with the additional business he would get from serving blacks. Whatever we might think of such a person (and I doubt there are many who would want to give him a medal for being such a rational calculator), the point is that his decision to discriminate need not be based on dislike for a particular racial group. Which means that our previous attempt to define racism in terms of actions motivated by racial animus must fail.

Next in Series: Racism without Racists?