The Church and the “Dangerous Memory” of 9/11:

Narratives of Fear, Narratives of Hope

The way the memory of 9/11 functions in American spirituality is nothing new. As Carolyn Marvin and David Ingle have shown in painful detail, American civil religion is a living tradition that depends upon the memory of violence as a primary means of identity formation [75]. September 11 is merely one of the most recent of these “interruptive” memories in a long history of selective memories that involve killing and dying for sake of the national community. What is perhaps unique about the memory of 9/11 is the openness with which it has been used to secure the global dominance of the United States by exerting military and economic power in what supporters and critics alike are describing as a “new imperialism,” or “American empire.” 9/11 has bolstered the militaristic tendencies of other nations as well, allowing them to use terrorism as an excuse for oppressive policies [76]. “There’s no telling how many wars it will take to secure freedom in the homeland” [77] Bush has warned the American people, and although the War on Terror has generated a massive protest movement and opposition from Republicans who fault Bush for “botching” the war in Iraq, a significant portion of Americans remain committed to the overall imperial vision, supported by an impoverished American spirituality of selective memory.

The way the memory of 9/11 functions in American spirituality is nothing new. As Carolyn Marvin and David Ingle have shown in painful detail, American civil religion is a living tradition that depends upon the memory of violence as a primary means of identity formation [75]. September 11 is merely one of the most recent of these “interruptive” memories in a long history of selective memories that involve killing and dying for sake of the national community. What is perhaps unique about the memory of 9/11 is the openness with which it has been used to secure the global dominance of the United States by exerting military and economic power in what supporters and critics alike are describing as a “new imperialism,” or “American empire.” 9/11 has bolstered the militaristic tendencies of other nations as well, allowing them to use terrorism as an excuse for oppressive policies [76]. “There’s no telling how many wars it will take to secure freedom in the homeland” [77] Bush has warned the American people, and although the War on Terror has generated a massive protest movement and opposition from Republicans who fault Bush for “botching” the war in Iraq, a significant portion of Americans remain committed to the overall imperial vision, supported by an impoverished American spirituality of selective memory.

These new realities inspire a question and a profound challenge for the Church: who or what shapes our memories? As Chomsky, Robin, and Blum have shown us, the media plays a large role in shaping and selecting which memories influence our imaginations, and thus, our spiritualities. Catholic theologian William Cavanaugh, drawing on the work of Benedict Anderson who defined nations as “imagined political communities,” suggests that the nation-state has replaced the Church as the “primary cultural institution that deals with death,” giving meaning to the meaninglessness of death, and providing a “new kind of salvation.” In a passage that echoes the concerns of Metz‘s theology, Cavanaugh says “death is not in vain if it is for the nation, which lives on into a limitless future” [78]. The nation is in the business of filtering and controlling the memories of its citizens, and giving those memories meaning, which shapes the national community’s imagined character and its lived practices. Memories are organized and given meaning through the nation’s own “liturgies” which are every bit as “religious” as Christian liturgy: the pledge of allegiance, honoring the flag, remembrance of the sacrifice of dead soldiers, or the various rituals that are used to remember the 9/11 attacks. Frequently, as in the case of the War on Terror, this controlled, narrow sense of historical memory results in a “dangerous spirituality” that forms a social body willing to send its children off to kill and be killed in the name of the nation-state. These controlled memories become “dangerous” in the literal sense, in that they end up creating new victims of violence rather a spirit of solidarity and resistance against the taking of human life.

The Church has an important task in this historical moment, particularly in the American Catholic Church, and must continually reclaim its role as the bearer of collective memory, the “emancipative memory, liberating us from all attempts to idolize cosmic and political powers and make them absolute” [79]. “Religion,” Metz says, “is essentially resistance to th[e] cultural amnesia” that allows human communities to perpetuate acts of violence.

This is especially so for Christianity. The Church as an institution is above all a collection of recollections, a long-term memory, an ‘elephant’s memory’ in which much, all too much, is stored: liberation and oppression, light and darkness [80].

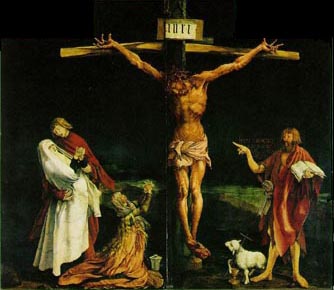

The Church must be the place where dangerous stories of the memory of violence are kept alive so that they may challenge us to resist violence in the present. Scholars tell us that the death of Jesus of Nazareth would have been just another forgotten crucifixion in the history of the Roman empire had the Church not kept his dangerous memory alive. In the same way, if the official rhetoric of the nation-state glosses over the dangerous portions of its history, neglecting its victimization of others, the Church must witness to the memory of the state’s victims. When the media fails to report the killing of a Guatemalan archbishop for investigating human rights violations in his country, rendering his death a “non-event” in the lives of most Americans, then the Church must witness to these dangerous memories. At the same time, the Church must continually be honest about its own memory and the ways in which it has neglected the victims within its own history [81].

The Church must continually renew within itself the eschatological dimension of Christian life, the forward-looking memory of hope in the promise of God, lest the memories of human suffering that are part of our history become dangerous in another sense:

If the catastrophic and continuous nature of time is not understood, the experience of catastrophe on the part of the individual confronted with death will be even more catastrophic and death will be even more deadly. A society and a church without a Christian apocalyptic vision has, in other words, made death more deadly [82].

The Church must continue to proclaim “We will never forget,” not in reference to the isolated, selective memories that incite vengeful responses, but primarily in reference to the dangerous memory of Christ and to the promise God has made to remember all the victims of history, those celebrated with monuments and parades as well as those forgotten and despised.

__________

75. Carolyn Marvin and David Ingle, Blood Sacrifice and the Nation: Totem Rituals and the American Flag (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999).

76. Chomsky, 217-8.

77. Quoted in Chomsky, 207.

78. William T. Cavanaugh, “The Liturgies of Church and State,” Liturgy 20, No. 1, 25-30.

79. Metz, FHS, 91.

80. Metz, “In The Pluralism,” 174.

81. Ibid.

82. Metz, FHS, 178.