Whenever I write posts like this one, I often find comments complaining about excess state power interfering in market-driven outcomes. Of course, Catholic social teaching has always acknowledged the role of the civil power in rectifying injustice (including economic injustice), and has done so in especially stark terms since Rerum Novarum.

Much of the criticism I see in comboxes and elsewhere derives from the standpoint of liberalism, whether explicitly or implicitly. Liberalism, of course, denies that the state has any duties toward God. Under liberalism, the individual is paramount and the state is a purely human creation designed to enforce a social contract between individuals and whose chief function is law and order. In the United States in particular, a philosophy that exalts individual freedom is closely entwined with the dominant Calvinist-Protestant tradition of seeing material success of a sign of virtue and divine favor. Of course, Protestantism and liberalism share common roots.

Catholicism, in contrast, has always seen society as an organic whole, not as a mere collection of individuals. This social order puts the state at the top, charged with oversight of the common good. The Church has always insisted that the state had a duty to care for the poor and promote economic justice. This took on a whole new meaning during the Industrial Revolution, and the Church responded with force. We all know the teachings of Rerum Novarum, where Pope Leo XIII argued strongly that market outcomes are not necessarily synonymous with justice, condemning the “callousness of employers and the greed of unrestrained competition” and the “concentration of so many branches of trade in the hands of a few individuals”. It goes without saying that Leo saw a positive role for the state in reining in the excesses of the free market – he says explicitly that “wage-earners, who are, undoubtedly, among the weakest and necessitous, should be especially cared for and protected by the commonwealth”.

Pope Pius XI in Quadragesimo Anno draws this out even further: “With regard to civil authority, Leo XIII, boldly breaking through the confines imposed by Liberalism, fearlessly taught that government must not be thought a mere guardian of law and of good order..The function of the rulers of the State, moreover, is to watch over the community and its parts; but in protecting private individuals in their rights, chief consideration ought to be given to the weak and the poor.” His namesake, Pope Pius XII, said something very similar: “And, while the State in the nineteenth century, through excessive exaltation of liberty, considered as its exclusive scope the safe-guarding of liberty by the law, Leo XIII admonished it that it had also the duty to interest itself in social welfare, taking care of the entire people and of all its members, especially the weak and the dispossessed, through a generous social programme and the creation of a labor code” (quoted in Thomas Storck, Is the Acton Institute a Genuine Expression of Catholic Social Thought?)

Redistribution thus becomes a valid function for the state. Pius XI concluded that the “riches that economic-social developments constantly increase ought to be so distributed among individual persons and classes that the common advantage of all”. And Pope John XXIII noted that “the economic prosperity of a nation is not so much its total assets in terms of wealth and property, as the equitable division and distribution of this wealth”.

So clearly, there is a strong role for the state in the economic sphere. It is incumbent on the state to step in and rectify wrongs, especially by empowering subsidiary mediating institutions such as trade unions. The guiding principle is not individual liberty but the common good. In the first place, the state does not intervene directly, but facilities the twinning of solidarity and subsidiarity by empowering unions and setting various norms of economic justice (such as pay and benefits). And the government may legitimately use the tax and expenditure system for the purposes of redistribution.

Pope John Paul II puts this very well in Centesimus Annus: “the State has the duty of watching over the common good and of ensuring that every sector of social life, not excluding the economic one, contributes to achieving that good, while respecting the rightful autonomy of each sector…the State must ensure wage levels adequate for the maintenance of the worker and his family, including a certain amount for savings…The State must contribute to the achievement of these goals both directly and indirectly. Indirectly and according to the principle of subsidiarity, by creating favourable conditions for the free exercise of economic activity, which will lead to abundant opportunities for employment and sources of wealth. Directly and according to the principle of solidarity, by defending the weakest, by placing certain limits on the autonomy of the parties who determine working conditions, and by ensuring in every case the necessary minimum support for the unemployed worker”.

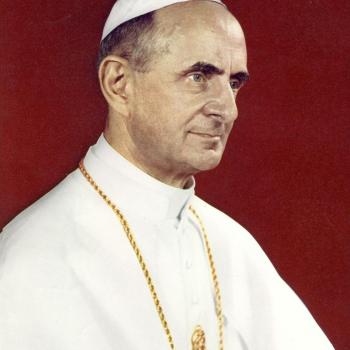

Of course, the state cannot solve every problem, and must act with a spirit of humility, respecting other autonomous entities. It can also go too far – and John Paul warns about this in Centesimus Annus (this admonition is sometimes misinterpreted by Catholic liberals as a turning away from earlier Catholic social teaching). But the state must not be restrained from acting by a liberalism or a Protestant ethic that regards market outcomes as virtuous and which sees liberty as paramount. Pope Paul VI in Octogesima Adveniens notes that liberalism has some attractions “against the increasingly overwhelming hold of organizations, and as a reaction against the totalitarian tendencies of political powers” but nonetheless “the very root of philosophical liberalism is an erroneous affirmation of the autonomy of the individual in his activity, his motivation and the exercise of his liberty”.

In sum, as noted by Thomas Storck, both individuals and society are ordered toward virtue, not freedom as the highest end. The error that freedom trumps virtue, justice, and the common good is the error of Lucifer himself.