This post was written in tandem with an earlier piece, titled “The Fire This Time.”

This post was written in tandem with an earlier piece, titled “The Fire This Time.”

In 1976, the evangelical church of my youth celebrated the bicentennial of American independence. Since my dad was the pastor and my mother the music director, my brothers and I were often pressed into service as singers. For our big Independence Day service, I was given the following song, titled “Statue of Liberty,” to sing, which I did with conviction:

In New York Harbor stands a lady,

With a torch raised to the sky;

And all who see her know she stands for

Liberty for you and me.

I’m so proud to be called an American,

To be named with the brave and the free;

I will honor our flag and our trust in God,

And the Statue of Liberty.

On lonely Golgotha stood a cross,

With my Lord raised to the sky;

And all who kneel there live forever

As all the saved can testify.

I’m so glad to be called a Christian,

To be named with the ransomed and whole;

As the statue liberates the citizen,

So the cross liberates the soul.

Oh the cross is my Statue of Liberty,

It was there that my soul was set free;

Unashamed I’ll proclaim that a rugged cross

Is my Statue of Liberty!

When I look back now all these years later, this song strikes me as the rankest kind of idolatry, suggesting a co-dependent synergy between Christ and country, Christianity and American civil religion, the cross and a copper-clad national symbol. At the time, the United States had just emerged from the disastrous Vietnam War and was barely 12 years beyond passage of the Civil Rights Act, which had formally ended 100 years of segregation in the South. Our national government had only recently been convulsed by the corruption of Watergate, the Sexual Revolution had firmly taken hold of American culture, and the American people were tumbling into the maw of debt and fantasy that is now bringing us to ruin. In 1976, our nation was, truth be told, hardly worthy of even the patriotic portions of the song, much less a favorable comparison with the passion, death and resurrection of Jesus Christ.

In a previous post, I wrote that “the solution to our problems can be found in one word: conversion. Conversion will not improve the GDP, put people back to work, or protect us from terrorism, but conversion will save us as a people.” I’d like to clarify up front what I do not mean by “conversion,” before moving on to explain what I do mean.

Conversion does not mean a reversion to the kind of syncretism demonstrated by the lyrics of “Statue of Liberty.” Such a reversion whitewashes American history, sanctifies unregulated capitalism, glorifies war, extols global empire, casts the poor as society’s sinners, succors bigots, and reduces personal morality to a set of banal platitudes that not even its high priests take seriously. It represents a false Gospel ideally suited for a people who have forgotten what the Gospel is, and what it demands.

Conversion does not mean a retreat from the public square into an insular piety focused exclusively on personal holiness and salvation. That sort of self-absorbed spiritual onanism is already the practical posture of many serious Catholics, but it is without warrant in scripture and in the teaching of the Church. The heart of the Gospel is loving self-donation, and the symbol of that self-donation is the Cross. Those who counsel separation from the world often cite our Lord’s words, “Render unto Caesar the things that are Caesar’s, and unto God the things that are God’s.” But as Dorothy Day noted: “If we rendered to God all the things that are God’s, there would be nothing left for Caesar.”

The Latin origin of the word “conversion” is convertere; literally, “to turn around.” In the ceremony for Ash Wednesday, which inaugurates the penitential season of Lent, the celebrant admonishes us to “Turn away from sin and be faithful to the Gospel” while tracing the sign of the cross in ashes on our foreheads. This ritual act is meant to symbolize a dying to self. It is at once a reminder of our baptism, when we were “buried with Christ,” and the inevitable end of our earthly lives, when our bodies will return to the dust and ashes of earth. The “turning” to which we are called involves both a renunciation and an embrace. We turn “from” sin and “toward” the Gospel, from ourselves and toward others, from the pride of life (which is death) and toward the cross (which is life). The enabling and validating mechanism of this “turning around” is repentance. Repentance includes the very specific acknowledgement that our priorities are disordered, that we are facing in the wrong direction. It focuses on concrete acts – sins – but also incorporates dispositions of the heart and mind – sinfulness. Repentance is the expression of regret for our disorderliness, but also incorporates the sincere intention to complete our turning toward light and life. Without repentance there is finally no turning: we remain oriented toward that which is bringing us to ruin.

What, you may ask, has any of this to do with bringing back to life the zombie nation that is the United States? The answer is plain. We need conversion, not just as individuals, but as a people. We need to confess our sins, both the acts we’ve committed as well as the dispositions of our national heart, dispositions found in the ideologies we cultivate, ideologies of selfishness, pleasure, and domination. We need to repent, expressing profound regret for what we’ve done to ourselves and our posterity, our fellow men and women, and nature itself. Moreover, our regret must be accompanied by the firm intention to change, to become a different kind of nation, to turn from the paths of exploitation, materialism, and violence and toward humility, justice, compassion, and peace.

Conversion will mean turning away from the doctrinaire Liberalism that dominates American political culture. Liberalism is the ideology that brought us both abortion on demand and our ruinous consumer ethos. Liberalism inspired the American myth of rugged individualism, which persists today in a culture that welcomes charity but sneers at justice. Liberalism replaced the rich human culture of craft, faith, and family with the mechanical values of efficiency and technique. As Edward Cahill, SJ, wrote in his book, The Framework of a Christian State, “Liberalism, is in thought (or philosophy), rationalism; in politics, secularism; in economics, greed; and in religion, indifferentism.”

Conversion will also mean turning away from the cult of American exceptionalism, by which we have justified everything from the mass-murder of Native Americans to pre-emptive war inIraq. It will mean turning away from our addiction to war making and empire. Conversion will mean a renunciation of our hyper-consumptive lifestyles; of an economic system based on the exploitation of labor and nature; of a political system that routinely ignores the common good in favor of narrow interests; and of a celebrity culture that privileges the dissolute and idiotic over the virtuous.

And what shall we turn toward? Catholic Social Teaching (CST) provides a starting point, a conceptual framework for incorporating the Gospel into the social, economic, and political life of the nation. The United States Conference of Catholic Bishops identifies seven key themes in CST:

Life and Dignity of the Human Person

The Catholic Church proclaims that human life is sacred and that the dignity of the human person is the foundation of a moral vision for society. This belief is the foundation of all the principles of our social teaching. In our society, human life is under direct attack from abortion and euthanasia. The value of human life is being threatened by cloning, embryonic stem cell research, and the use of the death penalty. The intentional targeting of civilians in war or terrorist attacks is always wrong. Catholic teaching also calls on us to work to avoid war. Nations must protect the right to life by finding increasingly effective ways to prevent conflicts and resolve them by peaceful means. We believe that every person is precious, that people are more important than things, and that the measure of every institution is whether it threatens or enhances the life and dignity of the human person.Call to Family, Community, and Participation

The person is not only sacred but also social. How we organize our society—in economics and politics, in law and policy—directly affects human dignity and the capacity of individuals to grow in community. Marriage and the family are the central social institutions that must be supported and strengthened, not undermined. We believe people have a right and a duty to participate in society, seeking together the common good and well-being of all, especially the poor and vulnerable.Rights and Responsibilities

The Catholic tradition teaches that human dignity can be protected and a healthy community can be achieved only if human rights are protected and responsibilities are met. Therefore, every person has a fundamental right to life and a right to those things required for human decency. Corresponding to these rights are duties and responsibilities–to one another, to our families, and to the larger society.Option for the Poor and Vulnerable

A basic moral test is how our most vulnerable members are faring. In a society marred by deepening divisions between rich and poor, our tradition recalls the story of the Last Judgment (Mt 25:31-46) and instructs us to put the needs of the poor and vulnerable first.The Dignity of Work and the Rights of Workers

The economy must serve people, not the other way around. Work is more than a way to make a living; it is a form of continuing participation in God’s creation. If the dignity of work is to be protected, then the basic rights of workers must be respected–the right to productive work, to decent and fair wages, to the organization and joining of unions, to private property, and to economic initiative.Solidarity

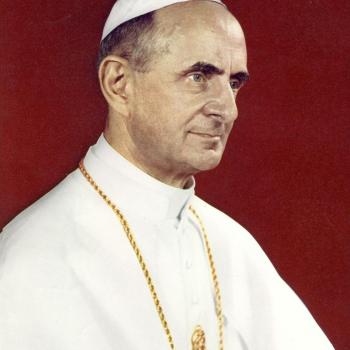

We are one human family whatever our national, racial, ethnic, economic, and ideological differences. We are our brothers’ and sisters’ keepers, wherever they may be. Loving our neighbor has global dimensions in a shrinking world. At the core of the virtue of solidarity is the pursuit of justice and peace. Pope Paul VI taught that “if you want peace, work for justice.” The Gospel calls us to be peacemakers. Our love for all our sisters and brothers demands that we promote peace in a world surrounded by violence and conflict.Care for God’s Creation

We show our respect for the Creator by our stewardship of creation. Care for the earth is not just an Earth Day slogan, it is a requirement of our faith. We are called to protect people and the planet, living our faith in relationship with all of God’s creation. This environmental challenge has fundamental moral and ethical dimensions that cannot be ignored.

Some will scoff that these principles sound vaguely “leftist,” at least in an American political context. But the problem isn’t the principles themselves; they are the Gospel distilled and applied to our common life. The problem is a sinful, disordered American political context dominated by two interchangeable political parties competing for money and power. Some will argue that other nations are as bad or worse. But which of us approaches the confessional having examined someone else’s conscience? Some will argue that on balance the United States has been a force for good. But who among us recites the Act of Contrition while enumerating our many good qualities and commendable acts? Would such contrition be sincere, or efficacious? Some will say that calling for the conversion of America is impractical since such a thing is not likely to happen. I agree. We are so entrenched, so invested in our collective sinfulness that howls erupt from Hawaii to Maine when a President or other national figure even appears to apologize for some minor American misdeed. Our myths and ideologies still possess us, and our corrupting pride is stronger still. Brokenness is a precondition for genuine conversion, but we are not yet a broken people. And so I agree that calling America to conversion is impractical, but as Mother Teresa said, God doesn’t require us to succeed. He requires us to try.

An old friend asks whether there is a place for the theological virtue of hope in this context, and of course the answer is “Yes!” But we must face reality. The United States does not have an exemption from either history or human nature. There is no special blessing upon us, no divine guarantee of rectitude and success. To believe such a thing is idolatry, pure and simple. Ours is an ordinary country filled with ordinary people. And so, we must have an ordinary kind of hope, and that hope must be in God, not in a man-made Constitution or the fallible men who wrote it.